This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Modern African Art

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Offering a wealth of perspectives on African modern and Modernist art from the mid-nineteenth century to the present, this new Companion features essays by African, European, and North American authors who assess the work of individual artists as well as exploring broader themes such as discoveries of new technologies and globalization.

- A pioneering continent-based assessment of modern art and modernity across Africa

- Includes original and previously unpublished fieldwork-based material

- Features new and complex theoretical arguments about the nature of modernity and Modernism

- Addresses a widely acknowledged gap in the literature on African Art

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Modern African Art by Gitti Salami, Monica Blackmun Visona, Dana Arnold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

1

Writing African Modernism into Art History

Narrations of Modernism and Modernity

Modernity has taken many forms. It may be understood as the emergence – after centuries of global commerce – of cosmopolitan outlooks adopted by local cultures negotiating with one another across vast geographic distances, and across gulfs of profoundly incompatible cultural conceptions. Exchange of material culture has been accompanied by trade partners’ cultural translations and highly selective rejection or incorporation of foreign objects and ideas. Genuine mutual admiration for the trade partner’s respective “Other” at times characterized this traffic in newness. However, significant power imbalances governed the terms of these exchanges during much of their duration, and continue to do so today.

Modernism, modernity’s expressive aspect, has as many local and regional variants as modernity itself. Until recently, those in control of the discourse within the international art world saw modernism’s European variant – in reality, one of many local forms – as normative. Specific features characterizing French artistic movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century are still regarded as a set of universal principles, standards that might be used to evaluate modernism worldwide, and Paris was seen as a center to peripheral modernisms located elsewhere. The notion of a French “avant-garde,” as an example, as Gitti Salami (chapter 29) points out, has militaristic connotations, suggesting that its intellectual feats typically entail rupture, shock, and conquest of unknown territory.1 Such paradigms are alien to those African societies that embrace newness via conceptual frames stressing ancestral authority and continuity within egalitarian principles and consensus-building. The notion of the “avant-garde” is only one of the filters rendering African modernisms simply invisible to art historians. As dele jegede (chapter 18) notes, Paris, London, and New York were cities teeming with African, African American and Afro-Caribbean intellectuals and artists throughout the twentieth century, yet African epistemologies were never considered when “standard” art historical canons were established. This volume provides many perspectives that challenge dominant, yet unexamined, paradigms. It thus contributes to a broad international endeavor, shared by artists, critics, and art historians alike, that would move beyond Eurocentric models to less parochial representation.

For African artists in particular, being modern has implied a progressive outlook, a desire to inscribe new contemporary experience with meaning. Just as European and American modernists have absorbed insights offered by African figurative representations in their painting and statuary, utilized knowledge of African ceremonies and body arts in their performances, and drawn on their impressions of African shrines in their installations, African modernists have studied the “traditional” art of Europe and Asia. They have incorporated responses to Chinese painting in their pen and ink washes, Turkish imagery in their reverse-glass paintings, Italian Renaissance figures in their sculpture, and, as Monica Blackmun Visonà shows (chapter 9), top hats in their performances. As citizens of the world, generations of African artists have sought to contribute to an international art world. Acknowledgment of their successes in the past usually omitted their names; though, in rare cases, as Sylvester Ogbechie has shown, some African artists were afforded short-lived celebrity status within international art circuits, but were subsequently written out of history.2

African modernist explorations can be traced as far back as the late fifteenth century. Frequently, these are a matter of continuously adapting indigenous institutions and practices to new circumstances, as many of the chapters in this volume demonstrate.3 Other African modernisms have been intellectual, interdisciplinary responses to new educational models and artistic frameworks. As contributors to this volume explain, some of the new venues in which African artists were trained upheld the standards of elite foreign institutions. Others were products of a colonial system that sought to train workers for the colonial empire – and in many cases both types of educational institutions had been altered for a local or national context. Individuals of varied backgrounds, including custodians of “traditions,” masters of workshops or royal guilds, commercial artists, and academically trained artists, have shaped local and national art infrastructures that promote particular forms of art and train future artists. Two strands of modernism – one based in indigenous culture and the other in foreign-derived institutions – variously coexist as separate platforms for artistic creativity, but they are simultaneously intertwined, often inextricably so. Together, they reflect not only the tension between the local and the global that typifies modernisms worldwide, they also model tremendous command of the paradoxes induced by the meshing of diametrically opposed value systems. Writ large, modern African art brings the expertise of sophisticated artists (at work on the continent for centuries) into the academic discourse swirling around the “antinomies of art and culture” in the contemporary, postcolonial world.4

Centering Narratives on Africa’s Art Worlds

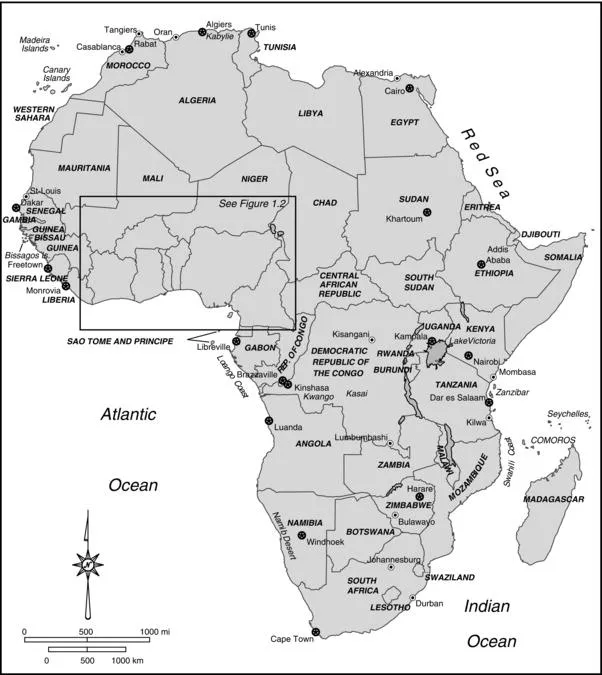

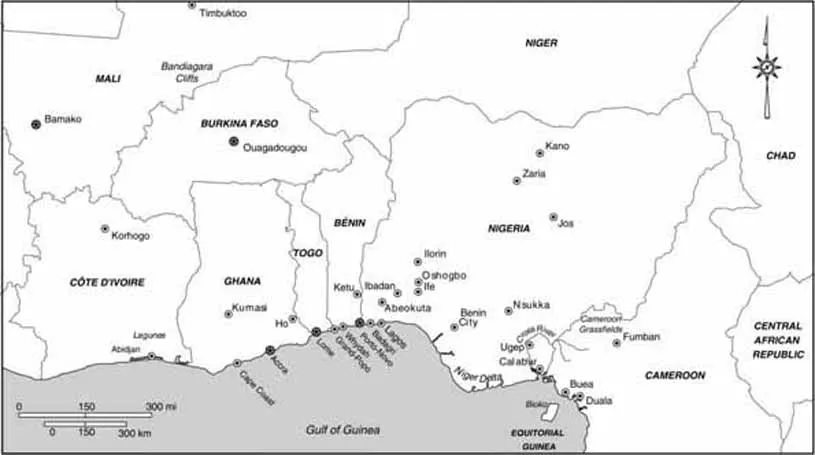

A Companion to Modern African Art foregrounds just one slice of a larger corpus of artistic production tied to Africa; it highlights African artists who live and work (or who have lived and worked) on the continent (Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2). The 29 case studies place a premium on African artists’ agency and their grounding in African epistemologies. This focus upon Africa challenges sophisticated arguments, some of which are raised by the contributors themselves. In her chapter on Swahili visual culture, Prita Meier (chapter 5) critiques the practice of grouping artists by their place of origin or the current location of their practice, reminding the reader that the dominant discourse on modernism foregrounds time rather than space; by writing about art that is geographically bound – particularly if writing about art on the African continent – Africanists write its artists out of history. Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu also feel that Africa as a classification has outlived its usefulness, for the mechanisms of the contemporary world are global.5 While these perspectives are intriguing, they unwittingly validate the outmoded idea that African artists must have a place within the dominant discourse if they are to be taken seriously. This assumes that Eurocentric though this discourse may be it is the only framework we need to consider. Rustom Bharucha is one of the critics who believes that this discourse need not be central to our debates, particularly since Europe “is scarcely at the center of the world any longer, politically or ideologically.”6 As Salah Hassan and Iftikhar Dadi point out in a pivotal and groundbreaking catalogue, Unpacking Europe, Europe and Europe’s “Other” constituted each other; the latter, racialized and subjugated, acted as “a foil against which Europeaness struggled to emerge.”7

FIGURE 1.1 Map of the African continent. Richard Gilbreath, Gyula Pauer Center for Cartography and GIS, University of Kentucky.

FIGURE 1.2 West Africa, detail from the map of the African continent. Richard Gilbreath, Gyula Pauer Center for Cartography and GIS, University of Kentucky.

Henry Drewal reminds us in chapter 2 that the currents of modernity are “rarely unidirectional.” The fact that Western explorers did not document what terms Africans used in the nineteenth century to describe the phenomenon of “modernity” hardly means that Africans did not define or debate it. Nor does the fact that European definitions of modernity prevailed therefore mean that Europe invented modernity, or that the rest of the world is bound by those definitions. Thus Nichole Bridges’ deconstruction of the reliefs carved onto ivory tusks from the Loango coast (chapter 3) would suggest that Kongo (Vili) engaged in lively, even humorous debates about changes to their sociopolitical and economic environment in the late nineteenth century, and that their images were partially designed to transmit these debates to foreigners. She explains that Loango ivories helped shape European and American understanding of modern Africa; particularly as some of these artists carved their wares in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower for the Universal Exposition of 1889 in Paris!8 Gilane Tawadros points out that “the world is . . . littered by modernities and by practicing artists, who never regarded modernism as the secure possession of the West,”9 while Ali Mazrui argues that Europe’s claim to universality has no legitimacy, given the cultural, historical, and empirical relativism embedded in its own modernism.10 The idea that Africa can move “beyond its Eurocentric provincialization,” as Paul Tiyambe Zeleza puts it,11 to become an equal actor on a decentered world stage, is altogether feasible. It is a perspective many of the volume’s authors entertain.

dele jegede (chapter 18) joins other critics and scholars who would abandon an “African art history” for a “diasporic art history.” He makes the case that the notion of “Black art,” which conceives of Africa in conceptual terms, is a more viable construct than “African art,” whose origins lie in the “terms and conditions” of the West. “Black art,” or even “Black Atlantic art,” emphasizes the continuities between artists of African descent across the globe and often pays tribute to Pan-African ideology and the philosophy of Négritude as historical bases for contemporary attempts to counter a hegemonic Eurocentric discourse. By subsuming African artists within diasporic art (created both by descendants of enslaved captives brought to the Americas, Europe, and Asia against their will, and by members of later diasporas provoked by vast economic inequalities and the political instability of neocolonialism) critics can bring a vast pool of talent within their purview. To a substantial degree, this view of the African continent’s creative production as a “subtext to the main story” (as Sidney Kasfir characterizes it in chapter 26) now predominates in the literature.12

Artists of the Diaspora do have pivotal roles in many local and national narratives on the continent, of course, and are noted throughout this volume. Ikem Okoye (chapter 6), for example, demonstrates how the creativity of architects born in Brazil inspired an early African modernism in architecturally innovative structures. Yacouba Konaté (chapter 19) traces the contributions of diasporic intellectuals, artists, and educators on both cultural policies and art movements in Côte d’Ivoire. Likewise, the concerted effort of contemporary transnational African artists, scholars, and curators to insert themselves into the power structure of the international art world, as discussed in greater detail by dele jegede (chapter 18) and Kinsey Katchka (chapter 25), has had significant repercussions in Africa. One might say their success has inspired confidence in African artists, which in turn has led to bolder attempts at communication with a global audience and even to improvements for the continent’s art infrastructures. Abdellah Karroum’s exhibition space L’Appartment 22 in Rabat, Morocco, discussed by Katarzyna Pieprzak (chapter 22), and workshops in Uganda based on the Triangle model, discussed by Sidney Kasfir (chapter 26) are cases in point. Not only does the influence of these transnational artists and culture brokers surface in many of the volume’s essays, but one could say that A Companion to Modern African Art owes its very conception to a shift in the discipline they created. Prior to the mid-1990s, a pioneering group of scholars, such as Ulli Beier,13 Jean Kennedy,14 and Janet Stanley,15 labored to bring African modernism into the art historical and critical mainstream, with little success. As Okwui Enwezor, Salah Hassan, Olu Oguibe (in the USA), and Simon Njami (in Europe) drew scholars’ attention to contemporary African art, they infused the field with critical theory, redirecting much of the discourse in African art history. Their publications are required reading for scholars of global...

Table of contents

- Cover

- WILEY BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO ART HISTORY

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: “Africa Has Always Been Modern”

- Part III: Art in Cosmopolitan Africa: The Nineteenth Century

- Part IV: Modernities and Cross-Cultural Encounters in Arts of the Early Twentieth Century

- Part V: Colonialism, Modernism, and Art in Independent Nations

- Part VI: Perspectives on Arts of the African Diaspora

- Part VII: Syntheses in Art of the Late Twentieth Century

- Part VIII: Primitivism as Erasure

- Part IX: Local Expression and Global Modernity: African Art of the Twenty-First Century

- Index