This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Setting out the debates and reviewing the evidence that links health outcomes with social and physical environments, this new edition of the well-established text offers an accessible overview of the theoretical perspectives, methodologies, and research in the field of health geography

- Includes international examples, drawn from a broad range of countries, and extensive illustrations

- Unique in its approach to health geography, as opposed to medical geography

- New chapters focus on contemporary concerns including neighborhoods and health, ageing, and emerging infectious disease

- Offers five new case studies and an fresh emphasis on qualitative research approaches

- Written by two of the leading health geographers in the world, each with extensive experience in research and policy

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Geographies of Health by Anthony C. Gatrell, Susan J. Elliott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Describing and Explaining Health in Geographical Settings

Chapter 1

Introducing Geographies of Health

“Code Red” refers typically to a state of emergency within a hospital; it indicates that something is terribly wrong and needs to be addressed with all urgency. In 2010 this phrase was used to indicate a general state of health emergency in neighborhoods in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, during a week-long public health event. Why?

Hamilton is home to a legacy of health-related issues. With a diverse population close to half a million people, it is a (former) industrial city in the heart of the Great Lakes region, once home to one of the largest steel manufacturing operations in North America along with its attendant environmental and social issues (contaminated air and water, a large working-class population, and substantial immigration). The local economy is now driven primarily by education (Hamilton hosts a large, research-intensive university, McMaster) and health care (an integrated set of health care institutions, linked to an innovative medical school).

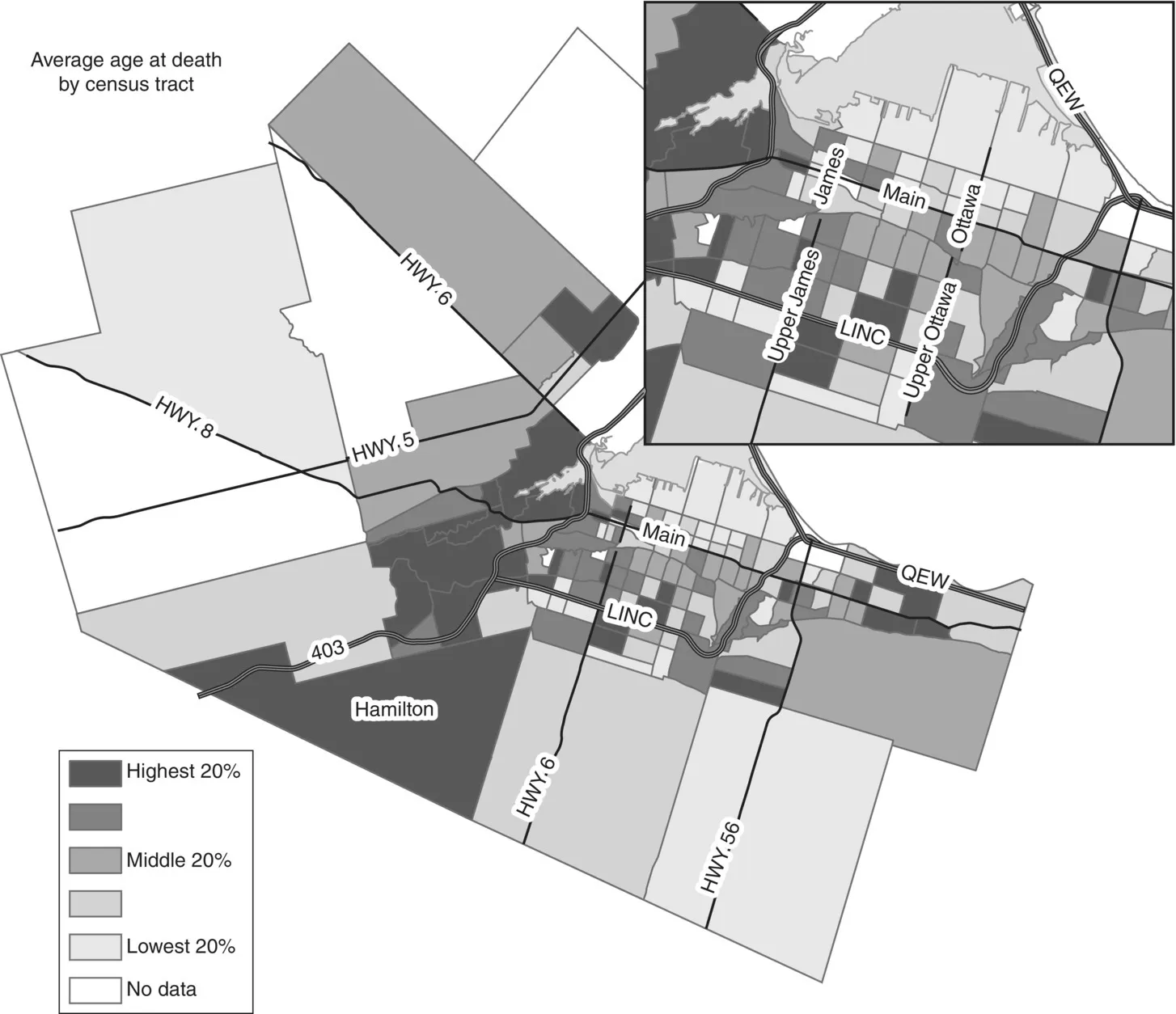

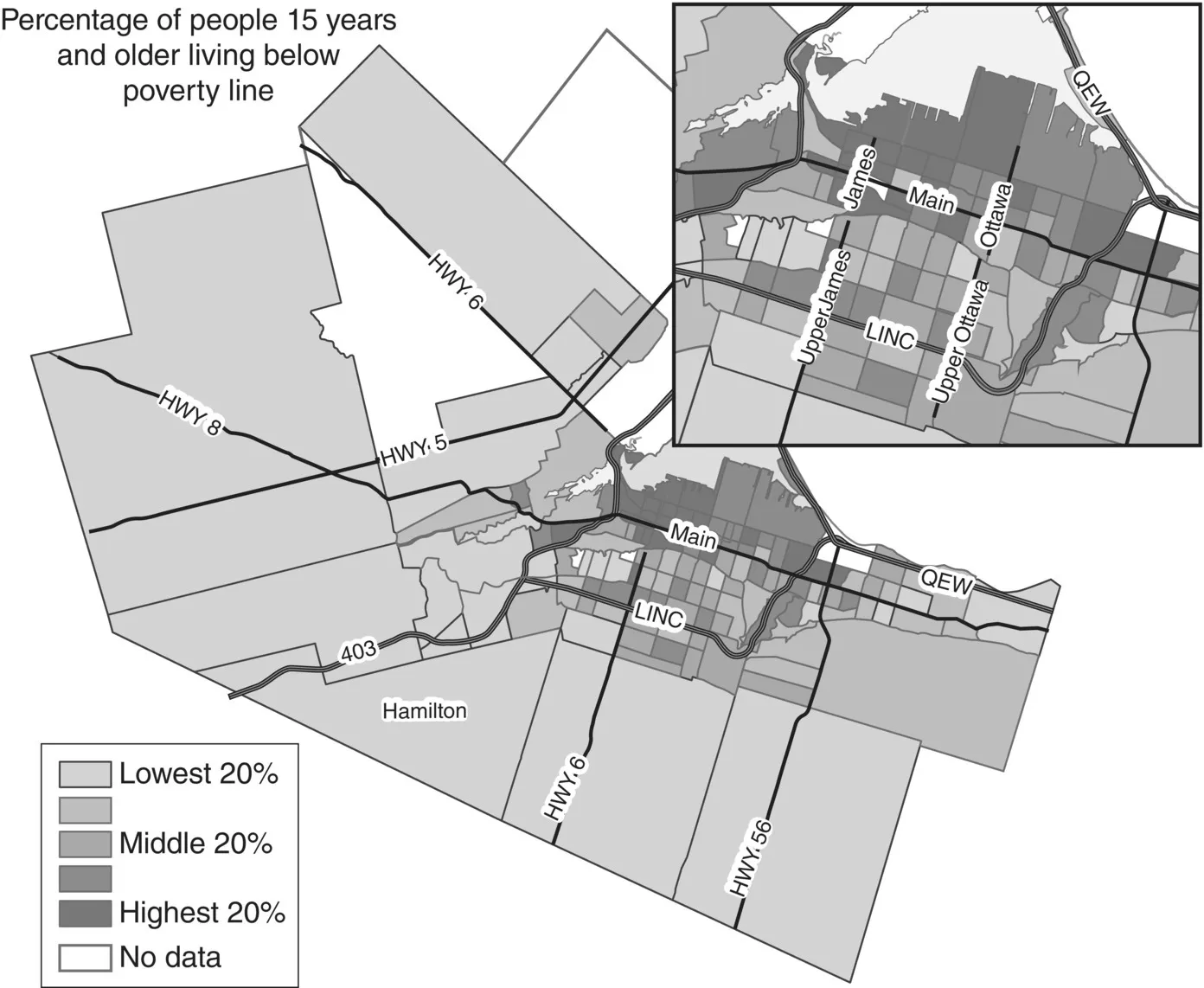

“Code Red” all started as a collaborative mapping exercise between city public health officials and university researchers at McMaster. But the champion for this week-long event was a local investigative journalist named Steve Buist, recipient of a Canadian National Newspaper Award for this work. He had begun to wonder about the geographical variations in health he was seeing across the city of Hamilton, especially given that Hamiltonians – like all Canadians – are privileged to have a universal health care system, free of financial barriers. Big questions plagued him. Why, for example, is there a 21-year difference in life expectancy between some of the city's neighborhoods? Why, in such a well-off community, do we see a neighborhood where nearly half of all babies are born underweight; three times the rate of that in some developing countries? And why, when post-secondary education is heavily subsidized by the state, do we see one neighborhood where almost 700 adults in every 1000 has a university degree, compared with another where virtually none have a university degree? (The Hamilton Spectator, April 10, 2010, p. 1.)

To make these issues – quite literally – visible, consider two maps (Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2), one showing average age at death, the other the distribution of people living on very low incomes. What is immediately apparent is that the two maps generate similar patterns; further, these patterns are similar across a broad range of health outcomes and social determinants of health, such as poverty, education levels, unemployment, quality of the housing stock, access to amenities like shopping and public transportation, not to mention health care facilities. And these patterns, which are far from random, tell us that our health is heavily dependent upon where we live.

Figure 1.1 Average age of death: Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Source: McMaster Spatial Analysis Laboratory.

Figure 1.2 People living below the poverty line: Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Source: McMaster Spatial Analysis Laboratory.

We aim to convince you in the course of this book that our “health” and our “geographies” are inextricably linked. The screening we get for diseases will be available differentially from country to country or from one health region to another. Where you live affects the treatment you get. The risks arising from environmental contamination, be this poor air quality or polluted groundwater, are not uniform over space. If you live on a busy main road, or near a site disposing of hazardous waste, you may be more at risk of illness than others who do not. Where you live affects your risk of disease or ill-health and therefore your well-being. Access to basic resources, such as nutritious food, clean water, decent housing, and rewarding (and properly rewarded) employment is also geographically differentiated. Where you live affects how accessible or available are such resources. These relationships are further complicated if you experience any type of disability; typically, access to resources to enhance health and well-being is greatly hindered.

If you approach this book with a geographical imagination already well developed via other books or courses you will, we hope, find the statements above uncontroversial, though if you are new to geographies of health we intend to persuade you that the subject of “health” is a rich source of material that bears study by the geographer. If we can stimulate more of you to take up “geographies of health” as an area for further enquiry or research we will be delighted. But we hope, too, to interest other readers; those who come to the subject with a background in health research – perhaps public health, general practice, or nursing – or another social or environmental science, and who are intrigued by what geographers might have to say on the subject.

To set the scene, we need to explain some basic ideas and concepts. For some readers (perhaps some geographers) we need to say something about health, illness, disease, and disability. These are high-level concepts which are far from unproblematic, but we will endeavor to say something about these in this first chapter so that some of the early material makes sense. For other readers (primarily non-geographers), we need to introduce some fundamental geographical principles and concepts.

Having laid some of this groundwork we want to consider five case studies: examples of work we consider as part of geographies of health. Our purpose in describing these studies is two-fold. First, we wish at a very early stage to introduce some pieces of research in the geographies of health in order to capture the imagination. Second, we intend to use them in order to show something of the richness and diversity of geographical research on health. There are several contrasting approaches to “doing” geographies of health, and there is no single style of enquiry accepted by those working within this field. We shall not say very much in this chapter about these different styles, though we hope it will be clear from what we do say that the differences exist. Instead, we shall leave until Chapter 2 the task of explaining how these five studies differ, and we shall use other examples to show how there are, broadly speaking, five alternative modes of explanation within the geographies of health. It will emerge later that this classification is far from clear-cut, but it serves as a useful organizing device. It will also become clear from the rest of the book that by no means are all approaches widely used in studying the geographies of health. Nonetheless, we think it is essential at an early stage to set out different styles and approaches to understanding the geographies of health.

Health and Geography: Some Fundamental Concepts

This section considers some concepts needed for a basic understanding of “health” and of “geography.” These two terms are examined separately – and in a real sense the remainder of the book represents an attempt to show the intimate connections between the two. Clearly, entire books are devoted to each; our aim is simply to provide some ideas that will aid the grasp of material later in this book.

Concepts of health

Health has been defined in many ways. In 1957, the World Health Organization invited us to see health as more than simply the absence of disease; rather, “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being” (World Health Organization, 1957). This ideal state does not, however, assist us very much since, according to the definition, most if not all of us are unhealthy at all times! We could instead take health to mean the availability of resources, both personal and societal, that help us achieve our individual potential. This is consistent with a definition of health (Epp, 1986), stemming from the Ottawa Charter, where health is defined as a resource for everyday living that allows us to cope with, manage, and even change our environments. Alternatively, we might think of health as being physically and mentally “fit” and capable of functioning effectively for the good of the wider society. Linked to this is the idea of health as personal or mental “strength,” fitness, or energy, or engaging in what we might think of as healthy behaviors or lifestyles (drinking alcohol in moderation, getting regular physical exercise). Further still, we could think of health as a commodity, to be given or lost, bought or sold; we “invest” in health perhaps by taking out private health care insurance, and lose it when we break a leg or become ill. Clearly, then, there are many ways to construct “health.”

Consider how you behave if you feel unwell. This might take the form of a headache or a sore throat. In the first instance you would possibly decide to manage this symptom yourself, perhaps by taking to bed or by self-medication using an over-the-counter remedy. If the symptoms persisted, or took a different form, you might consult a health professional: perhaps a nurse in a clinic, or a general physician. You do this because the symptoms represent a departure from your usual healthy state. You may be examined and tested for signs of some underlying pathology or disturbance in the body's functioning. You experience some discomfort, some pain perhaps; you feel ill. Illness, then, is a subjective experience. The health professional, however, is concerned to offer a diagnosis; to “identify the specific underlying pathology in the patient's body that is producing the signs and symptoms, distinguish it reliably from other possible diagnoses, and label it correctly with the name of a medically recognized disease” (Davey and Seale, 1996: 9). Put simply, people suffer illnesses, while doctors diagnose diseases. The doctor or physician wishes, then, to cure the patient of the disease; the patient will, of course, wish to be cured of any disease, but also wants to be freed from feeling ill.

Disease and illness may or may not be associated, in that it is perfectly possible to feel ill without there being any detectable biological abnormality, while the person who has been diagnosed with such an abnormality might feel quite well. For example, those who are debilitated by a feeling of complete lethargy may find that a health professional is unable to detect any obvious “cause” (and hence conditions such as myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME – also known as chronic fatigue syndrome – may go unrecognized by doctors; it may be a condition they are not prepared to diagnose; see Clauw et al., 2003 and Krieger, 2005 for an extended discussion). Equally, a middle-aged man w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- PART I: Describing and Explaining Health in Geographical Settings

- PART II: Health and the Social Environment

- PART III: Health and Human Modification of the Environment

- Index

- End User License Agreement