Infectious Disease Surveillance

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Infectious Disease Surveillance

About this book

This fully updated edition of Infectious Disease Surveillance is for frontline public health practitioners, epidemiologists, and clinical microbiologists who are engaged in communicable disease control. It is also a foundational text for trainees in public health, applied epidemiology, postgraduate medicine and nursing programs.

The second edition portrays both the conceptual framework and practical aspects of infectious disease surveillance. It is a comprehensive resource designed to improve the tracking of infectious diseases and to serve as a starting point in the development of new surveillance systems. Infectious Disease Surveillance includes over 45 chapters from over 100 contributors, and topics organized into six sections based on major themes.

Section One highlights the critical role surveillance plays in public health and it provides an overview of the current International Health Regulations (2005) in addition to successes and challenges in infectious disease eradication.

Section Two describes surveillance systems based on logical program areas such as foodborne illnesses, vector-borne diseases, sexually transmitted diseases, viral hepatitis healthcare and transplantation associated infections. Attention is devoted to programs for monitoring unexplained deaths, agents of bioterrorism, mass gatherings, and disease associated with international travel.

Sections Three and Four explore the uses of the Internet and wireless technologies to advance infectious disease surveillance in various settings with emphasis on best practices based on deployed systems. They also address molecular laboratory methods, and statistical and geospatial analysis, and evaluation of systems for early epidemic detection.

Sections Five and Six discuss legal and ethical considerations, communication strategies and applied epidemiology-training programs. The rest of the chapters offer public-private partnerships, as well lessons from the 2009-2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic and future directions for infectious disease surveillance.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

SECTION TWO

Program Area Surveillance Systems

6

Active, population-based surveillance for infectious diseases

2Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

3International Emerging Infections Program, Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US CDC Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand

4Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, MN, USA

Introduction

Emerging infections programs: an overview

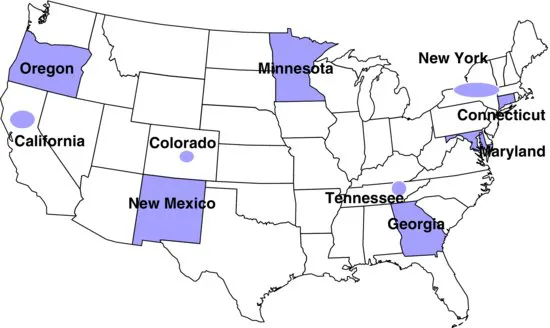

Active Bacterial Core surveillance

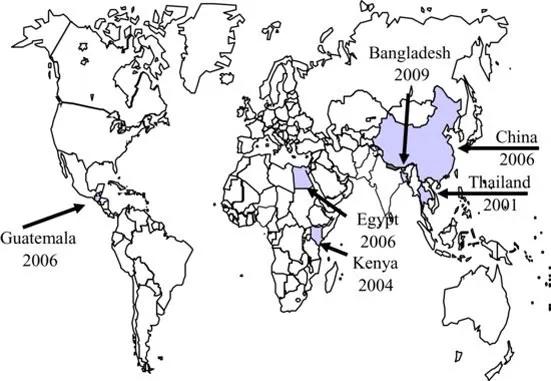

International Emerging Infections Program

Definition and rationale for active, population-based surveillance

Methodology: setting up active, population-based surveillance

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Foreword to the Second Edition

- Foreword to the First Edition

- Preface to Second Edition

- Preface to First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Weighing of the Heart

- SECTION ONE: Introduction to Infectious Disease Surveillance

- SECTION TWO: Program Area Surveillance Systems

- SECTION THREE: Internet- and Wireless-based Information Systems in Infectious Disease Surveillance

- SECTION FOUR: Molecular Methods, Data Analyses, and Evaluation of Surveillance Systems

- SECTION FIVE: Basic Considerations, Communications, and Training in Infectious Disease Surveillance

- SECTION SIX: Partnerships, Policy, and Preparedness

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app