- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studying Comics and Graphic Novels

About this book

This introduction to studying comics and graphic novels is a structured guide to a popular topic. It deploys new cognitive methods of textual analysis and features activities and exercises throughout.

- Deploys novel cognitive approaches to analyze the importance of psychological and physical aspects of reader experience

- Carefully structured to build a sequenced, rounded introduction to the subject

- Includes study activities, writing exercises, and essay topics throughout

- Dedicated chapters cover popular sub-genres such as autobiography and literary adaptation

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What’s in a Page: Close-Reading Comics

Comics seem more straightforward than written texts. Because they have images, it appears that everyone understands immediately what is going on their pages. However, as you begin to seriously consider comics and the way they tell their story, you will realize that also analyzing comics is a skill that has to be practiced. Close-reading comics is the first stepping stone toward understanding how they unfold their meaning. This chapter will explain how reading comics works by relating the elements of the comics page to what is going on in your mind as you make sense of them. It also introduces the basic terms you will need for your own comics’ analysis.

Cognitive Processes and Critical Terms

The comic strip from the web comics series Sinfest you will find on the next page seems immediately accessible: it presents a short dialogue between a boy and a girl. The girl seems to be in control of the situation, dispensing advice to the boy, until he turns the situation around in the final panel as he challenges her moral superiority. Yet this account short-circuits your encounter with this comic: when you read a panel like the first one, your mind begins taking in all kinds of information from the images and the written text – the facial expressions, gestures, and postures of the CHARACTERS, their speech, the layout of the image and many other features. These are clues for you to make sense of the panel and the event it represents. You identify clues, you draw inferences from them, and you integrate these inferences into the basic pattern of the story. These processes are not conscious proceedings, but something which you do (almost automatically). If you want to analyze comics critically, it makes sense to consider how the clues on the page and the inferences they suggest tie in with how you make sense of the comic. The cognitive processes involved in reading comics are usually pre-conscious, that is, you would not be aware of them when you are actually reading a comic, but they contribute fundamentally to your meaning-making.

Figure 1.1 Sinfest (I). Source: Sinfest: Viva La Resistance™© 2012 Tatsuya Ishida.

First, however, in order to make the analysis as specific as possible, I will briefly introduce some basic terminology for the comic and its elements. The Sinfest comic is structured into four panels which are the boxes within which you see the characters. Each panel presents something like a snapshot of the action, relating to what has happened before and suggesting how the event might continue. Within the panels, you see the characters and you can read their communication in the SPEECH BUBBLES. Speech bubbles are spaces within which the characters’ words are rendered in written text. The tail of the speech bubble is connected to the mouth of the speaker, allowing you to relate the written text to its speaker. When the speech is not located with a speaker in the image, it is rendered in a caption, a box usually at the top left-hand corner of the panel.

As you make your way through a panel, your might first get a (very rough) impression of the entire panel. This is an impression of the number of characters and their general spatial relation to each other, as well as the number of speech bubbles and their connection to the characters. This is the snapshot aspect of the panels. In the first panel, for example, you can see at first glance that the girl is in control. She is the only one speaking, privileged by her position in the left-to-right reading direction of the panel, and she points at the boy, defining him. The boy, on the other hand, stands, with his hands in his pockets, which signals being relaxed. Without even reading the speech bubbles, we can tell that this power relationship will change in the final panel, because here the image shows us the protagonists from the other side of the encounter (which looks like the image has been flipped around), and the girl’s body suddenly tenses up. This information on basic power relationships and attitudes is something you can take in at a single glance, because they relate to your own bodily experience of the world. Try sitting up in your chair, and you will feel more alert; put your hands in your pockets and slump back, and you will be more relaxed.

When we see characters do something in a panel, the processes in our brains unfold something like an imitation of these postures in motorsensory systems which prepare the action (but do not lead us to actually perform it), and we feel an echo of the character’s experience. This has been discussed in terms of “embodied simulation” in the neurosciences. When an image relates characters to each other in its COMPOSITION, our BODY SCHEMA (that is, our motorsensory capacities, see Gallagher 2005) give us a sense of whether there is a balance or an imbalance between the characters, and how the dynamics of the relationship is going to unfold. In his discussion of the dynamics of composition in art, Rudolf Arnheim (2008) has noted how perception and our bodily experience of balance, gravity and other forces shape each other. What the cognitive sciences have found about the relation of body and mind suggests that a good part of our meaning-making is indeed grounded in our bodily experience of the world. A lot of information can be taken in at a single glance.

As you investigate the details of the panel then, your attention focuses and you read the speech bubbles. When you pay attention to the details of the panel, it begins to unfold through time, and a story emerges as you relate the first- glance information to the details you pick up now. The controlling attitude of the girl is confirmed, when we read that she indeed tells the boy “what you gotta do.” His smart tie and carefully groomed hair suggest that he thinks highly enough of himself to take care of his appearance. The sunglasses also contribute to this attitude of studied coolness. The clothes and the looks of characters give you a lot of information, based on social conventions and expectations, about the way they want to be perceived and about what is important to them.

The girl’s speech is modulated by her gestures (pointing at the boy, calling him to attention, and referring to herself) and her facial expressions of emotional states. It is also shaped by the emphasis of the letters in bold, which indicate stress in her voice. In her final word, “diva,” she seems to be positively yelling. Unlike the printed letters on a book page, the letters in speech bubbles have onomatopoetic qualities, which means that their size and boldness correspond to the volume at which they are spoken and the emphasis which is laid onto them. The bigger and bolder the letters, the louder the speech; the smaller and thinner the letters, the more quiet and subdued.

Paying attention to the details on the page fleshes out the basic impression that you get from the first glance. Your inferences get more precise and you get a clearer sense of what the story is about, of the interests and investments of the characters involved, and also of the likely course the action is going to take. The scene between the girl and the boy is set up as an encounter between two different attitudes: know-it-all versus studied cool. This is information which you can take from their body language, but also from the social knowledge you have about clothing style for example. In the beginning it looks like the girl has all the trumps in her hand: she is the only one speaking and shaping the space of interaction between them with her gestures (thereby assigning him a particular role in the encounter). Readers not only infer the meaning of the situation as it stands, but also project how the story will continue on the basis of their inferences: Will the boy accept the girl’s assessment of his tuition? Will he try to turn the situation around? Will he lose his cool? These are all questions raised by the first panel. As the following panels give answers to these questions and raise new ones, your inferences about the situation, the relations of the characters and the potential outcome will change constantly, and a narrative emerges as you establish connections between the events.

In this particular comic, the panel images represent a single situation, set in a single space, and the dialogue unfolds continuously. Other comics, however, might feature long temporal gaps between panels or they might change scenes completely between panels. The space between the panels is called the “gutter” , and just as you step across a gutter, your mind creates connections between the individual panels, by drawing inferences about how the action in the one can relate to the other, and thereby trying to integrate them into a single, meaningful narrative.

Scott McCloud calls the phenomenon of making sense between panels “closure” (1994, 67). To McCloud, who has a very broad-ranging understanding of closure, it is a process that turns readers into participants of the comics’ narrative as they supply the missing information between panels. Closure goes back to the so-called “principle of closure” in GESTALT psychology. We perceive the Figure 1.2 as a circle, even though it is in fact an assortment of curved lines. We close the visual gaps and see a complete shape rather than lines. However, this does not mean that we have a very precise sense of the lines that fill the gaps. We simply assume that they most likely continue in roughly the same color, thickness, and curvature that we observe in the parts of the circle that we do see. Once the principle of closure is moved to panel-to-panel transitions, there is the tacit assumption that we have the same characters and locations at a slightly later point in time but we do not run an inner film of how they got there.

Figure 1.2 Closure.

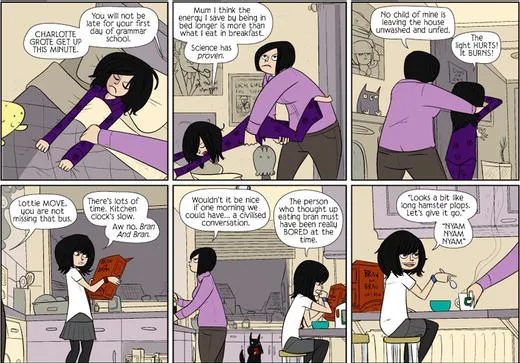

Consider the bodily forces of composition at work in the first row of panels in Figure 1.3. The composition of the two bodies describes a half-arc, and the impetus of the movement is from left to right. The movement of Charlotte’s mother determines Charlotte’s motion here, and it directs your attention. Like a wrestler, she seems to fling her daughter’s body along the left to right arc. Once we have a closer look at the background of the second and third panel, however, we notice that the movement is not continuous. The mother’s body has not just turned (which would be the easiest way for joining up the circle), but she has actually changed her position in the room.

The whole, the circle, we perceive, reflects the “mental model” we construct as we make sense of a narrative. We construct a mental model of the characters, the relations between them and the events that affect them. This mental model is the basis for the STORYWORLD, which we will discuss in the final section of this chapter (see Herman 2002). In some cases, such as the Sinfest and the Bad Machinery comics, this mental model is rather simple and straightforward. In other cases, developing a coherent mental model and a narrative out of your inferences presents much more of a challenge.

Figure 1.3 Bad Machinery.© John Allison.

What is a narrative in the first place? “The cat sat on the mat” is no narrative because nothing is happening. “The cat sat on the dog’s mat,” however, has the potential for a conflict and for a chain of actions to unfold, and it therefore constitutes a minimal narrative, as Gerald Prince (1982, 147) suggests. In the first instance, we can say that a narrative is a chain of events that sets up a conflict and that keeps us wondering about what will happen next. I will elaborate this account in the next chapter. For now, back to Sinfest.

The narrative movement of the encounter in Figure 1.4 is reflected in the composition of the comic as a whole. There are alternating changes between the perspective of the panels: panel 1 shows the little devil watching TV; in panel 2, when the TV set unexpectedly begins to interact with the devil, we have a similar jump across the axis of the gaze between TV and devil as in the final panel of Figure 1.1; panel 3 shows a view from being the devil; panel 4 reestablishes the perspective of the first panel. This reflects the ways in which the TV set gains ascendance over the devil. From an unobtrusive position in the right-hand corner of the panel, the TV set literally “jumps” into prominence (and the left-hand corner) in the second panel. It towers above the little devil in the perspective of the third panel until it moves back into the unobtrusive position of the forth panel. Through the arrangement of perspectives in the panels, the TV set seems to circle around the little devil, asserting its dominance from every angle. The changes of perspective between panels, and the movements of bodies across a strip or...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: How to Use This Book

- 1 What’s in a Page: Close-Reading Comics

- 2 The Way Comics Tell it: Narration and Narrators1

- 3 Narrating Minds and Bodies: Autobiographical Comics

- 4 Novels and Graphic Novels: Adaptations

- 5 Comics and Their History

- 6 The Study and Criticism of Comics

- Conclusion

- Appendix: More Comics and Graphic Novels to Read

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Studying Comics and Graphic Novels by Karin Kukkonen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.