This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the course book for a new ALSG course on preparation for and medical management of major incidents within the hospital. It will be a companion volume to MIMMS, which deals with the prehospital situation, and will meet an ever increasing need as natural and other disasters affect hospital staff and administrators. The course aims to provide a systematic approach for all personnel who would be involved in managing a major incident in the hospital.

This title is now available for the PDA, powered by Skyscape - to buy your copy Click here

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Major Incident Medical Management and Support by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

The epidemiology and incidence of major incidents

INTRODUCTION

A major incident is said to have occurred when an incident requires an extraordinary response by the emergency services. While major incidents may affect any of the emergency services, the health service’s focus is the resulting casualties. A major incident cannot, however, simply be defined in terms of the number of casualties—the resources available at the time of the incident are also relevant. For example, a road traffic accident in a remote area producing five multiply injured casualties may overwhelm the immediately available local resources. However, a similar incident in a major urban conurbation may require little or no additional resources. Thus, the same incident in different localities may produce a major incident in one but not in the other.

For the purposes of planning, major incidents have been defined as: events that owing to the number, severity, type or location of live casualties require special arrangements to be made by the health services’.

Local Highlights: Major incident definition

This definition is an operational one that recognises that major incidents occur when the resources available are unable to cope with the workload from the incident. The need to relate major incidents to the availability of resources is most clearly demonstrated when considering incidents that produce ‘specialist’ types of casualties. An incident producing paediatric, burned or chemically contaminated casualties may require the mobilisation of specialist services even when there are only a few casualties. This is because the expertise and resources needed to deal with these types of casualties are limited and widely scattered around any country.

Incidents such as plane crashes may occur in which all casualties are dead at the scene. Whilst these are clearly major incidents for the police and fire service, there is often little requirement for the health service beyond mortuary and pathology services. An example of such an incident was the Lockerbie air crash where all passengers were killed and only a few people were injured on the ground.

Classifying major incidents

Whilst the health service definition is an adequate one for planners at a local level, it does not tell us anything about the size of the incident or the incident’s effect on society as a whole.

Rutherford and De Boer have classified and defined major incidents with regard to their size and effect on the health service and society. This classification system is useful for emergency planners and researchers. Their system defines major incidents in three ways:

1. Simple or compound

2. Minor/moderate/severe

3. Compensated/uncompensated

Simple or compound. A simple incident is an incident in which the infrastructure remains intact. Compound incidents are those in which the incident destroys the infrastructure of society itself. Roads, communications and even the health services may be destroyed. Compound incidents typically arise as the result of war or natural disasters.

Size. While it is not possible to decide whether a major incident has occurred purely on the basis of the number of casualties involved, an appreciation of the size of incident can assist in the planning process for a major incident response. De Boer et al. divide incidents into minor, moderate or severe. This is shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Size classification of major incidents

| Size | Total number of casualties (alive or dead) | Casualties admitted to hospital |

| Minor | 25–100 | 10–50 |

| Moderate | 100–1000 | 50–250 |

| Severe | > 1000 | >250 |

Compensated or uncompensated. By definition, major incidents require the additional mobilisation of resources in order to deal with the health service workload. Incidents may be considered to be compensated if the additional resources mobilised can cope with the additional workload. When an incident is such that even following the mobilisation of additional resources the emergency services are still unable to manage, it is said to be uncompensated.

Failure to compensate may occur in three circumstances. First, the absolute number of casualties may be so large as to overwhelm the available health service resources. Second, the resulting casualties may require such specialised (or rare) skills or equipment that any more than a few casualties overwhelm resources. Such incidents may require relatively few casualties to reach this point, as there may be scant resources available to deal with them. Third, incidents occurring in remote areas may remain decompensated as the health services may be unable to reach the casualties.

The point at which decompensation occurs is often difficult to define and in many respects depends on the perspective of the observer. Total failure of the response to a major incident (such as the absence of any medical care) is clearly failure to compensate, and is most likely to occur in natural disasters or war. However, failure to compensate may also be considered to have occurred when the care given to individual patients is of a standard less than that acceptable in day-to-day practice. Decompensation is only considered to have occurred when the system fails to such an extent that individual patient care is seriously compromised.

At the present time little is known about the effectiveness of the health service response to major incidents as this information is rarely recorded or analysed. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that the care given to individual patients during major incidents is often below the standard that would be delivered in normal daily practice.

The all-hazard approach and special major incidents

Major incident planning should follow an ‘all-hazard approach’. This means that one basic major incident plan should be able to cope with all types of major incident. This is necessary as it is impossible for any emergency planner to predict the nature of the next incident. In addition, maintenance of separate major incident plans for all possible eventualities would be impractical. The all-hazard approach also allows planning to be kept as simple and as near to normal working practice as possible.

However, despite these guiding principles, there are still certain types of incident that require additional modifications to the basic plan. This is the only way to achieve the aim of optimal clinical management for as many casualties as possible.

Incidents involving chemicals, radiation, burns, infectious diseases or a large number of children are considered by many emergency planners as ‘special’ types of major incidents. Whilst it may be necessary to alter or embellish major incident plans to deal with these specific types of incidents, the required modifications should be made without significant departure from the basic (all-hazard) major incident plan. All these incidents are characterised by a type of casualty for which resources may be scarce. They may therefore result in a failure to compensate by the health services response even though there are relatively few casualties. Although these types of incident are considered separately, the general principles of emergency planning must still apply.

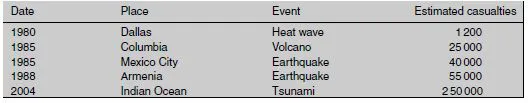

Natural disasters

It is worthwhile reiterating the difference between man-made and natural disasters when considering the epidemiology of major incidents. Natural disasters result from earthquake, flood, tsunami, volcano, drought, famine and/or pestilence. However, the potential for suffering and loss of life is enormous (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Natural disasters

On a world scale natural disasters are important but require a different type of response to the simple, compensated major incident more typical of those occurring in a developed society. Planners considering the response to a natural disaster in a foreign country face a challenge quite different from that presented in this book.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MAJOR INCIDENTS IN THE UK

Historically, major incident planning has been based upon military experience. As a consequence of this, many major incident plans have been developed to cope with a large number of traumatically injured adults. However, major incidents may occur for a variety of reasons and may produce many different types of casualties. Whilst it is impossible to predict the exact nature of the next major incident, there is little to be gained in planning for types of major incident that might never occur. By looking at the type of major incidents that have occurred in the recent past, planners can base their plans and major incident exercises on realistic scenarios.

Unfortunately, accurate data on the nature and incidence of major incidents are difficult to obtain. Little data are collected prospectively and the quality of available data is questionable. Despite these limitations some information is available from which better major incident plans can be formulated.

The incidence of major incidents

Many health care providers perceive major incidents to be extremely rare events. It is therefore not surprising that major incident planning has been accorded a low priority. If incidents are perceived as rare then emergency planners and health service staff may become complacent. It is perhaps no surprise that the most active time for major incident planning appears to be the period immediately after an incident has occurred, which is too late.

In order to examine the real need for major incident planning in Britain a 31-year review of major incidents occurring between 1968 and 1999 was conducted. In this study a major incident was considered to have occurred when 25 or more people had attended hospital, more than 20 had attended of whom 6 or more had suffered serious injury (ITU admission or multiple injuries) or when a major incident was known to have been declared by the ambulance service or receiving hospital. A total of 115 major incidents were identified. Although major incidents are perceived as rare the overall incidence over this period was 3–4 major incidents per year. However, for many years the data were incomplete. In recent years data are more reliable and an estimate of 4–5 major incidents occurred per year in years when data collection is known to have been good.

There are approximately 200 Emergency Departments in Britain. Any could receive casualties from a major incident. It follows that each hospital would expect a major incident every 28–30 years. However, as the majority of major incidents occur in population centres or along lines of mass transportation, hospitals in urban conurbations may expect a higher incidence. In addition, it is rare for only a single hospital to respond to a major incident (particularly in urban centres). The true estimate for any individual hospital is therefore difficult to calculate but an estimate of one every 10 years for urban hospitals would appear reasonable, with a lesser incidence in more rural settings.

Local Highlights: Number of major incidents per year

What type of major incidents occur?

The vast majority of incidents in the UK arise as the result of human activity. Incidents are usually characterised by a large number of people gathered together for work, travel or leisure. Occasional incidents may result from deliberate terrorist attacks or from other forms of social disorder.

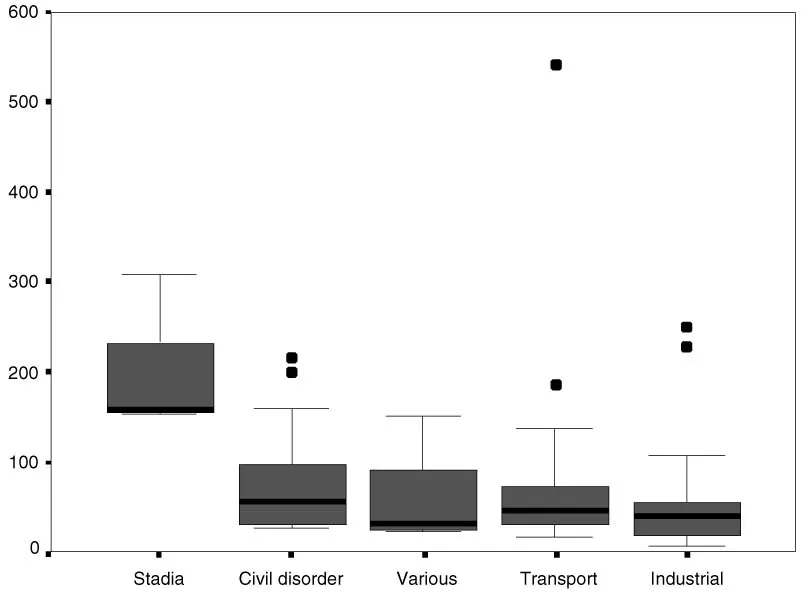

Although a wide variety of incidents occur they can be broadly subdivided into civil disorder (including terrorist incidents), industrial accidents, transportation accidents, sports stadium events and a variety of other miscellaneous types. In Britain between 1968 and 1996 63/108 (58%) incidents involved transportation accidents, 22/108 (20%) resulted from civil disturbances and industrial accidents account for 15/108 (16%). Sports stadium and other miscellaneous incidents comprise the remaining 6%. All these types of major incident are likely to be encountered again.

Transport related incidents form the majority of incidents occurring in the UK, with rail crashes being the single largest cause. Surprisingly, air crashes, although perceived as a common cause, rarely result in major incidents. This is because they result in a large number of deaths, but few survivors. Many major incident plans and exercises are tailored to receiving casualties from air crashes. Planners should look in particular at the response to all other forms of major incident when formulating plans.

Local Highlights: Types of major incident

How many patients should we plan for?

There appears to be no clear consensus as to how to predict the number of casualties. A variety of estimates for major incident plans have been made previously; some of these have been extremely unrealistic.

There are several aspects to consider when estimating the expected patient workload. First, the total number of casualties requiring medical attention is important as they will need to be processed and treated by the health services. Second, an estimate of the likely number of patients with injuries severe enough to warrant hospital admission, surgery, intensive care or specialist services would be useful.

Although the next major incident is unlikely to exactly replicate a previous one, an examination of past incidents can guide emergency planners as to the expected number of casualties that may result from major incidents. Figure 1.1 shows the total number of casualties in British major incidents.

Figure 1.1. Box plot of number of casualties by type of incident (median, interquartile ranges, 95% confidence intervals and outliers 1968–1999)

The majority of major incidents result in fewer than 100 casualties. It is therefore reasonable for emergency planners to ensure that their major incident plans are capable of receiving this number of casualties. The exception to this is the disproportionately large number of casualties seen in stadia related incidents when emergency planners might be expected to plan for up to 200 casualties.

Local Highlights: Number of casualties per major incident

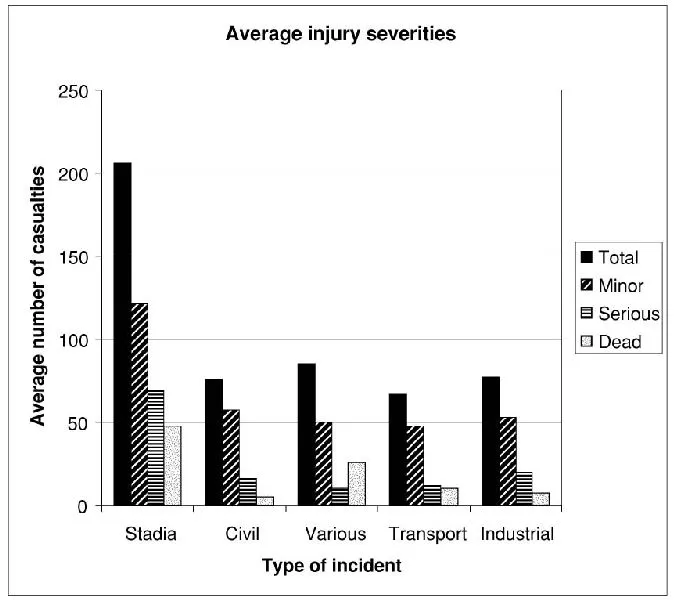

It is useful to look more closely at the number of live casualties, and in particular the number of casualties requiring admission to hospital. In 75 of the incidents studied between 1968 and 1996 it was possible to differentiate casualties into serious and minor. Serious casualties were those requiring admission to hospital, while minor were those treated and allowed home. It is clear that, on average, the number of casualties with minor injuries is at least twice that of those seriously injured.

For hospital planners an estimate of the number of patients requiring admission is useful. Figure 1.2 shows the range of seriously injured casualties seen in different types of incident.

Figure 1.2. Box plot of casualty admissions by type

Local Highlights: Number of serious casualties per major incident

These data suggest that hospitals in the UK should have major incident procedures that allow them to admit up to 40 patients for the majority of incide...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Contents

- Title page

- Copyright page

- AUTHORS

- WORKING GROUP

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CONTACT DETAILS AND FURTHER INFORMATION

- PART I: INTRODUCTION

- PART II: PREPARATION

- PART III: MANAGEMENT

- PART IV: SUPPORT

- PART V: SPECIAL INCIDENTS

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX