![]()

1

History of anaesthesia

Before the introduction of anaesthesia, it would not have been possible to carry out the majority of modern operations. Development of the triad of hypnosis, analgesia and muscle relaxation has enabled surgery to be performed that would otherwise be inconceivable.

Early attempts at pain reduction included the use of opium (described in Homer's Odyssey 700 bc), alcohol and coca leaves (these were chewed by Inca shamans and their saliva used for its local anaesthetic effect).

Attempts at relieving childbirth pain could (and did) result in accusations of witchcraft.

If surgery had to be performed, it usually involved restraint, administration of alcohol and the procedure being performed as quickly as possible (amputations often took a matter of seconds).

Nitrous oxide (N2O) was described and first synthesized by Joseph Priestly in 1772. It was used experimentally by Humphry Davy, who also introduced its use to London intellectuals at the time, such as the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, engineer James Watt and potter Josiah Wedgewood. Priestly also discovered oxygen, describing it as ‘dephlogisticated air’.

First documented anaesthetic

The first documented use of N2O was in North America, by Horace Wells (a dentist) in Hartford, Connecticut in December 1844, for a dental extraction in front of a medical audience. The patient cried out during the procedure (although later denied feeling any pain) and Wells was discredited, never to fully recover and eventually committing suicide.

N2O subsequently entered general dental practice in 1863.

Ether and chloroform

In October 1846, William Morton (also a dentist) used ether at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston during an operation on a neck tumour, performed by surgeon John Warren. Dr Oliver Holmes, who was present, described the state induced by ether as ‘anaesthesia’.

On 19th December 1846, ether was used in Dumfries (during a limb amputation of a patient who had been run over by a cart) and in London (for a tooth extraction).

James Simpson (Professor of Obstetrics in Edinburgh) introduced chloroform in November 1847, having discovered its effectiveness at a dinner party held at his house on 4th November that year.

John Snow administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of Prince Leopold (chloroform a la reine). Her positive endorsement of pain relief during labour removed religious objections to the practice at that time. (Snow is also famous for his epidemiological work, which identified the Broad Street water pump as the source of a cholera epidemic in London in 1854, confirming it as a water-borne disease.)

Chloroform was later replaced due to its toxicity and potential to cause fatal cardiac dysrhythmias.

Anaesthesia as a medical specialty

The development of anaesthesia as a specialty has been attributed to Joseph Clover. He advocated examining the patient before giving an anaesthetic as well as palpating a pulse throughout the duration of anaesthesia. He described cricothrotomy as a means of treating airway obstruction during ‘chloroform asphyxia’.

The development and use of local anaesthetics

Carl Koller (an ophthalmologist from Vienna) described the use of topical cocaine for analgesia of the eye in 1884, having been given a sample by his friend Sigmund Freud (the founder of modern-day psychoanalysis) who worked in the same hospital.

In 1884, William Halstead and Richard Hall, in New York, injected local anaesthetic into tissue and nerves to produce analgesia for surgery. The following year, also in New York, Leonard Corning, a neurologist, described cocaine spinal anaesthesia in dogs; he had inadvertently performed an epidural block. Six months later, Walter Essex Wyntner in the UK and Heinrich Quincke in Germany independently described dural puncture (this was used for the treatment of hydrocephalus secondary to tubercular meningitis).

In 1899, Gustav Bier performed spinal anaesthesia on six patients as well as on his assistant – who also performed the same procedure on Bier. They tested the efficacy of the anaesthetic on each other with lit cigars and hammers. Both reported significant post dural puncture headache, which at the time they attributed to too much alcohol consumed in celebration of their achievement. He also described intravenous regional anaesthesia (IVRA), in which local anaesthetic is injected intravenously (usually prilocaine) in a limb vein, with proximal spread prevented by a tourniquet – the Bier's block.

In 1902, Henry Cushing described regional anaesthesia (blocking large nerve plexi under direct vision in patients receiving a general anaesthetic).

The Spanish surgeon Fidel Pagés Miravé described epidural anaesthesia for surgery in 1921.

Typical career path in anaesthesia

- Medical School: 5–6 years;

- Foundation Programme: 2 years;

- Anaesthetic Training Programme or Acute Care Common Stem Training (ACCS; 2 years) consisting of 1 year of anaesthesia/intensive care medicine (ICM) and 1 year of acute and emergency medicine. If an ACCS trainee wants to continue in anaesthetic training they will enter year 2 of basic level training;

- Basic level training: 2 years (21 months of anaesthesia and 3 months of ICM);

- Pass the Primary Fellowship of the Royal College of Anaesthetists (FRCA) examination;

- Intermediate level training: 2 years;

- Pass the Final FRCA examination;

- Higher level training: 2 years;

- Advanced level training: 1 year.

Throughout all levels of training, summative assessments are carried out to ensure standards are achieved, with increasing responsibility and the opportunity for subspecialization in the more advanced years of training, for example paediatrics, obstetrics, cardiac, intensive care and pain management.

Useful links

Royal College of Anaesthetists: www.rcoa.ac.uk

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: www.aagbi.org

![]()

2

Monitoring

Routine monitoring can be divided into three categories.

The anaesthetist

The anaesthetist is continuously present during the entire administration of an anaesthetic. Information obtained from clinical observation of the patient, monitoring equipment and the progress of the operation allows for the provision of a balanced anaesthetic in terms of: anaesthesia and analgesia, fluid balance, muscle relaxation and general appearance (skin colour, temperature, sweatiness etc.).

The patient

The minimum monitoring consists of: electrocardiogram (ECG), pulseoximetry, non-invasive blood pressure, capnography and other gas analysis (O2, anaesthetic vapour), airway pressure, neuromuscular blockade; see Chapter 12.

The equipment

This includes: oxygen analyser, vapour analyser, breathing system, alarms and infusion limits on infusion devices. A means of recording the patient's temperature must be available, as well as a peripheral nerve stimulator when a muscle relaxant is used.

Other monitoring devices are used depending on the type of operation and the medical condition of the patient (e.g. to measure cardiovascular function). These include invasive blood pressure monitoring, central venous pressure, echocardiography, oesophageal Doppler and awareness monitors.

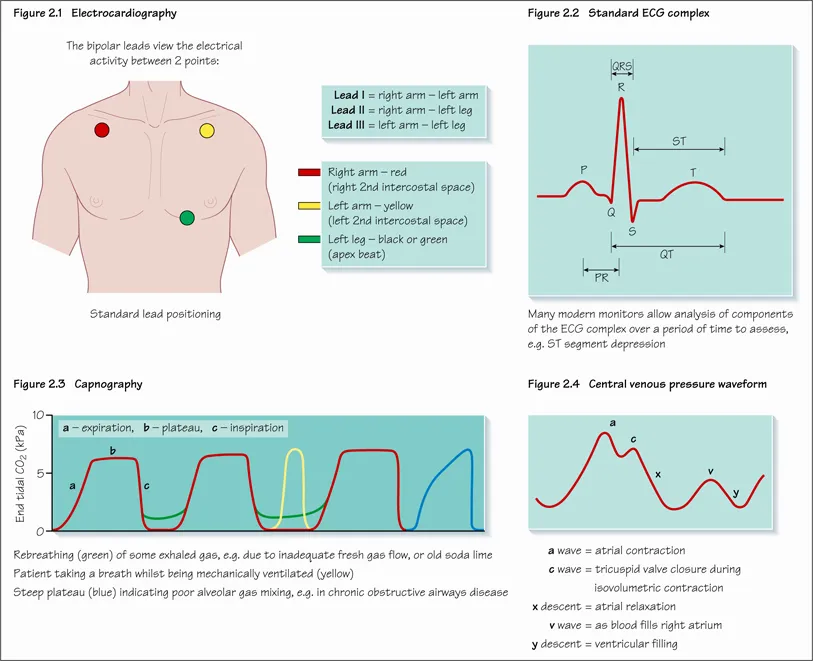

Electrocardiography (ECG)

Continuous assessment of the heart's electrical activity can detect dysrhythmias (lead II) (Figures 2.1 and 2.2) and ischaemia (CM5 position). Most commonly, the standard lead position is used. From this the monitor can be used to measure the electrical activity between two of the leads whilst the third acts as a neutral.

It is important to remember that the heart's electrical activity does not reflect cardiac output or perfusion, for example pulseless electrical activity (ECG complexes associated with no cardiac output) may be recorded.

Oximetry

A pulse oximeter consists of a light source that emits red and infrared light (650 nm and 805 nm) and a photodetector. The absorption of light at these wavelengths differs in oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin. Thus the relative amount of light detected after passing through a patient's body can be used to estimate the percentage oxygen saturation. The detecting probe is typically placed on the fingernail bed, or ear lobe, and only analyses the pulsatile (arterial) haemoglobin saturation.

Inaccurate readings may be caused by high ambient light levels, poor tissue perfusion (e.g. cardiac failure, hypothermia), cardiac dysrhythmias (e.g. tricuspid regurgitation), nail varnish, methaemoglobinaemia (under reads), carboxyhaemoglobin (over reads) or methylene blue (transient reduction in reading).

There can be a significant delay between an acute event (e.g. apnoea, airway obstruction, disconnection) and a reduction in the Sao2 especially if the patient is receiving supplemental oxygen, and any reading should be considered along with other monitoring parameters as well as clinical signs.

Blood pressure (BP) and cardiac output (Figure 5.4)

A cuff is inflated to above systolic pressure (or to a predetermined figure when taken for the first time in a new patient). A sensing probe detects arterial pulsation at systolic pressure. The maximum amplitude of pulsation is the mean arterial...