eBook - ePub

Endometriosis

Science and Practice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Endometriosis

Science and Practice

About this book

Written by an internationally well-known editor team, Endometriosis: Science and Practice is a state-of-the-art guide to this surprisingly common disease. While no cause for endometriosis has been determined, information of recent developments are outlined in this text, offering insight to improve management of symptoms medically or surgically. The first of its kind, this major textbook integrates scientific and clinical understanding of this painful disease helping to provide better patient care.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

History, Epidemiology, and Economics

1

History of Endometriosis: A 20th-Century Disease

Introduction

A reconstruction of the history of progress made in identifying, describing, and treating the condition we call endometriosis is neither simple nor easy because for almost 90 years endometriosis and adenomyosis, with the possible exception of ovarian endometrioma, were considered as one disease called “adenomyoma.” As such, historians must deal first of all with a controversy over who was the first to identify the benign, non-neoplastic presence of ectopic endometrium within the uterine wall or in the peritoneal cavity and structures. In addition, they must be aware that the early history of endometriosis is interwoven with the early history of adenomyosis, since it was not until the mid 1920s that the two conditions were finally separated.

Who identified endometriosis?

The history of medicine is full of controversies over who “discovered” a specific disease. In certain cases this is due to a desire to attribute the discovery to a researcher from a given country; in others, it is due to conflicting evidence, as sometimes disagreement focuses on the criteria utilized to attribute the discovery.

The latter situation is typical of endometriosis, a condition that does not lend itself to a purely clinical diagnosis. This is why, before embarking on a search for who “discovered” (a better word is definitely “identified”) it, it is necessary to fix a set of criteria, first and foremost what constitutes the “essence” of endometriosis. Some favor clinical descriptions, rather than histology or pathogenesis. Knapp, for instance, believed that the first descriptions of endometriosis can be found in Theses and Dissertations published in Belgium and The Netherlands during the second half of the 17th century [1], whereas Batt believes that endometriosis was discovered when the presence of heterotopic endometrial tissue was first described, even though the conditions were all labeled “sarcomas” [2].

We are of the opinion that the identification of the conditions we today distinguish in peritoneal and ovarian endometriosis and in adenomyosis (globally here called END-AD) must be based on the observation of the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity and on the specification that this invasion was “benign” in nature. Using these criteria, we will critically examine published information on the history of endometriosis.

The first information that needs to be evaluated is contained in a publication by Vincent Knapp [1]. In it, he explained that the disease we name endometriosis was already identified 300 years ago. His conclusion was based on a series of 11 inaugural dissertations presented at European universities between 1690 and 1795. The Disputatio Inauguralis Medica de Ulceribus Uteri by Daniel Christianus Schrön presented at the University of Jena in 1690 is now sometimes cited as the first description of endometriosis [3]. However, close scrutiny of some of the original manuscripts from this period has shown that the descriptions evidenced signs of inflammation such as pus, uterine wounds or erosions that were linked to manipulation, an abortion or a syphilitic lesion. The symptoms described were those of an infection and included pain, insomnia, fever, vaginal lesions, dysuria, purulent urine (if the lesion involved the bladder) or purulent stool (if the lesion involved the intestines). There were no descriptions in the Disputatio Inauguralis or in the other later dissertations that could be interpreted as being indicative of endometriosis. Sadly, Vincent Knapp passed away a few months after publication of his manuscript and a letter to the Editor of Fertility and Sterility remained without response [4].

A point that has been overlooked is that, without a microscope, these early authors had no way to even predict the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Therefore, applying the above-mentioned criteria, it becomes a physical impossibility for endometriosis to have been described during the 17th and 18th centuries. In addition, in those days abdominal surgery could not be performed and so, either the lesions were superficialm and therefore could not be “endometriotic” in nature, or they could have been observed only at macroscopic autopsy examination and there is no trace of this having been the case.

More complex is the situation with regard to Carl Rokitansky, who in 1860 described what Batt called “three phenotypes of endometriosis containing endometrial stroma and glands” [2]. The first consisted of two varieties labeled Sarcoma adenoids uterinum (invading the uterine muscular wall) and Cystosarcoma adenoids uterinum (a cystic variety associated to myometrial hypertrophy). The second, named Cystosarcoma adenoids uterinum polyposum, invaded the endometrial cavity forming a polyp and the third Ovarian-Cystosarcom invaded the ovary [5]. In an early paper on the history of endometriosis [6] we omitted any reference to Rokitansky on the basis of the “malignant nature” of his descriptions. Indeed, Rokitanski specifically mentioned:

… a sarcoma tissue in the form of papillary excrescences grow into the space of the cyst-like degenerated tubules. The slit-like, lacunar clefts scattered within the sarcoma produce on cross-section a granular appearance. The circumscribed nodes, which can be shelled-out, and appear incorporated in the sarcoma mass, doubtless originate from the filling of the great cyst spaces by intruding tumor tissue – a common appearance, which is especially pronounced in cystosarcoma adenoids mammarium.

To us, this is the description of a malignant tissue. Batt, however, insists that, in spite of the nomenclature, Rokitansky was aware of the benign nature of these invasions and that therefore he was the first to identify “the benign invasion of endometrial glands and stroma into the peritoneal cavity and organs” [2].

Setting aside the question of the nature of the lesions observed by Rokitansky, it is their origin that created a fierce controversy, with pathologists of the fame of von Recklinghausen [7] contending that lesions that were then called “adenomyoma” were the result of displacement of Wolffian or mesonephric vestiges.

When we examine the many and detailed descriptions of “mucosal invasions” of the peritoneal cavity and organs published at the end of the 19th and during the early part of the 20th century, we must conclude that the majority of pathologists rejected the hypothesis that the glands they observed were “endometrial.” As late as 1918, Lockyer, in detailing the various theories on the origin of epithelial glands and stroma found in the pelvis outside the uterine cavity, was unable to resolve the question of their origin. He wrote: “Nothing but the topography of the tumor, nothing but laborious research entailing the cutting of serial sections in great numbers, can settle the question as to the starting point of the glandular inclusions for many of the cases of adenomyoma” [8]. Therefore, earlier researchers who described mucosal invasions in the abdominal cavity, but failed to consider these invasions as being made of endometrial cells, cannot be considered as having “discovered” END-AD.

It was the surgeon Thomas Cullen (Fig. 1.1A) who described for the first time both the morphological and clinical picture of END-AD. In the preface to his book Adenomyoma of the Uterus, Cullen [9] wrote in 1908:

One afternoon in October 1882, while making the routine examination of the material from the operating room I found a uniformly enlarged uterus about four time(s) the natural size. On opening it I found that the increase in size was due to a diffuse thickening of the anterior wall … Examination of the(se) sections showed that the increase in thickness was due to the presence of a diffuse myomatous tumor occupying the inner portion of the uterine wall, and that the uterine mucosa was at many points flowing into the diffuse myomatous tissue.

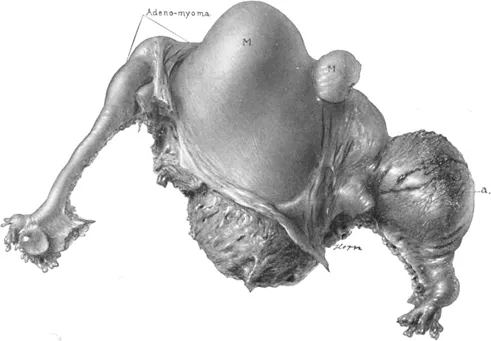

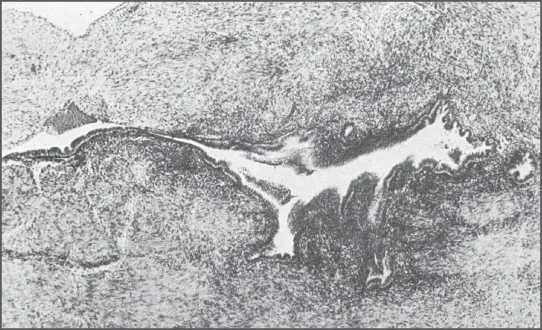

Over the following years Cullen collected 90 uteri with adenomyomata and described the various presentations of “adenomyomata” in the myometrial wall, uterine horn, subserosa and uterine ligaments and showed in the uterus the continuity between the endometrial glands and the glandular structures deep in the myometrium (Fig. 1.2). In addition, he was the first to describe decidualization of the stromal cells during pregnancy, providing the functional proof that the cells were of endometrial origin (Fig. 1.3). He was also the first to describe the symptoms of the uterine adenomyoma, and concluded rather optimistically:

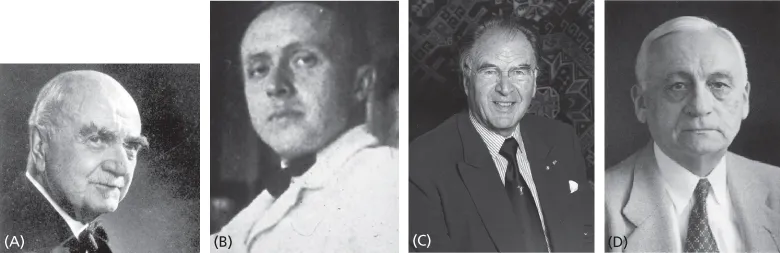

Figure 1.1 Gallery of pioneers in the study of endometriosis. (A) Thomas S. Cullen (1868–1953). Courtesy of Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. (B) John A. Sampson (1873–1946). Courtesy of Albany Medical College, New York. (C) Kurt Semm (1927–2003). Courtesy of Liselotte Mettler. (D) Emil Novak (1884–1957). Courtesy of Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Figure 1.2 Histological demonstration of the continuity between the endometrium layer and the adenomyotic tissue in the myometrium. Reproduced from Cullen [9] with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 1.3 Hysterectomy specimen with tubal pregnancy on the right side and deciduoma in the left uterine horn. Sections showed no connection between the cornual deciduoma and the endometrium. Reproduced from Cullen [9] with permission from Elsevier.

I cannot help feeling that anyone who reads the chapter on symptoms will agree with us that diffuse adenomyoma has a fairly defined clinical history of its own and that in the majority of cases it can be diagnosed with a relative degree of certainty.

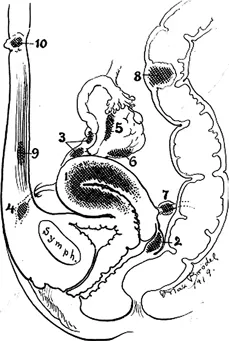

In 1920 Thomas Cullen [10] drew a scheme with the classic sites of adenomyotic lesions in the pelvis (Fig. 1.4). Adenomyoma involved ectopic endometrial-like tissue in the myometrial wall, rectovaginal septum, hilus of the ovary, uterine ligaments, rectal wall, and umbilicus. There is no doubt that Cullen considered uterine adenomyoma, ovarian endometriosis, and deep endometriosis as one disease characterized by the presence of adenomyomatous tissue outside the uterine mucosa.

Figure 1.4 Scheme with the classic sites of adenomyotic lesions in the pelvis according to Cullen (1921). 1 Myometrium; 2 rectovaginal septum; 3 fallopian tube; 4 round ligament; 5 ovarian hilus; 6 ovarian surface; 7 sacrouterine ligament; 8 bowel; 9 abdominal wall; 10 umbilicus. Reproduced from Cullen [10] with permission from Elsevier.

It is customary to consider John A. Sampson (see Fig. 1.1B) as the discoverer of endometriosis and indeed, his work on peritoneal and ovarian endometrioma provided the first theory on the pathogenesis of the disease. His original observation came when he operated on women at the time of menstruation and found that the peritoneal lesions were bleeding similarly to what happens in eutopic endometrium (Fig. 1.5) [11]. This proved to him that the tissue outside the uterus was of endometrial origin. In 1927 Sampson postulated that the presence of endometrial cells outside the uterus was due to tubal regurgitation and dissemination of menstrual shedding [12].

Figure 1.5 Endometriotic implant on the ovary showing shedding and bleeding of the endometrium-like tissue at the time of menstruation. Reproduced from Sampson [11] with permission from American Medical Association.

Clearly, peritoneal endometriosis became the signature of the disease and with the introduction of laparoscopy in the 1960s, a golden tool became available for visual diagnosis and surgical therapy. As a result, endometriosis was divorced from the uterus and research became focused on how fragments of menstrual endometrium implant on peritoneal surfaces and invade the underlying tissues. Since menstrual regu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 History, Epidemiology, and Economics

- 2 Pathogenesis

- 3 Disease Characterization

- 4 Biological Basis and Pathophysiology of Endometriosis

- 5 Models of Endometriosis

- 6 Diagnosis of Endometriosis

- 7 Medical Therapies for Pain

- 8 Surgical Therapies for Pain

- 9 Infertility and Endometriosis

- 10 Associated Disorders

- Plates

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Endometriosis by Linda C. Giudice, Johannes L. H. Evers, David L. Healy, Linda C. Giudice, MD,Johannes L. H. Evers, MD,David L. Healy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gynecology, Obstetrics & Midwifery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.