![]()

SECTION 1

Understanding the disease process

![]()

1

The structure and function of the periodontium

Kevin Stepaniuk and James E. Hinrichs

Periodontium

The supporting apparatus of the tooth is known as the periodontium. The gingiva, periodontal ligament (PDL), cementum, and alveolar bone are the tissues of the periodontium (Figure 1.1). This unique collection of tissues has a functional role in the oral cavity beyond anchoring the tooth in the bone. Understanding the structural, functional, biochemical, immunological, and molecular aspects of the periodontium is necessary to understand the pathophysiology of periodontal disease, periodontal treatments, periodontal regeneration, and periodontal repair. The hard tissues (cementum and bone) and the soft tissues (PDL and gingiva) of the periodontium play active rolls in the local inflammatory and immune response by synthesizing and releasing cytokines, growth factors, and enzymes. This fascinating interrelation of tissues, along with the normal apoptosis of the cells of the periodontium, provides the backdrop for the continued battle between periodontal health and disease.

Odontogenesis and the periodontium

Odontogenesis is the embryological events in tooth development. Complete tooth development is described elsewhere.1 However, the development of the tooth is not isolated from development of the periodontal tissues. During enamel development an outer enamel epithelium (OEE), inner enamel epithelium (IEE), and stellate reticulum are present. Adjacent to the enamel epithelium are the ectomesenchymal cells that form the dental follicle and papilla. The dental follicle gives rise to the cementum, PDL, and some alveolar bone.2 This ectomesenchymal embryonic tissue forming the dental papilla and follicle is derived from neuroectoderm.2

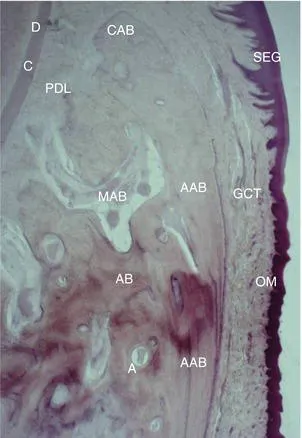

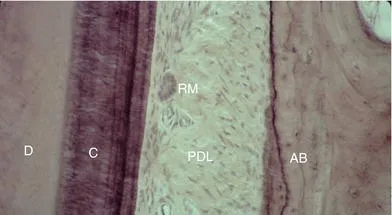

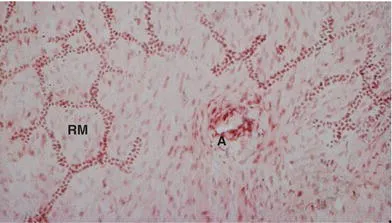

The tooth root forms after the crown has developed, but before it is completely mineralized. The OEE and IEE, without the stellate reticulum, develop into Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath (HERS). HERS proliferates into the underlying connective tissue to form the root. The dental papilla is stimulated to form odontoblasts, which produce dentin. At this stage, the root sheath breaks up and cementoblasts are formed from the adjacent ectomesenchymal tissue. This inductive, interactive ectodermal-ectomesenchymal pattern of tooth and periodontium development is conserved in most higher vertebrate species.3 HERS cells can remain trapped in the periodontal ligament and are known as the epithelial rests of Malassez (ERMS) (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). These cells, if stimulated later in life, may become cysts or possibly odontogenic tumors.4,5 However, it is debated whether the ERMS are sources of odontogenic tumors.

The enamel epithelium proliferates into a thick reduced enamel epithelium that fuses with the oral epithelium.6 The gingiva forms as the crown of the tooth penetrates into the oral epithelium and erupts into the oral cavity. A dentogingival junction is created and the junctional epithelium is established.

Repair and/or regeneration of the periodontium share many of the same events that occur during development of these unique tissues. A complete understanding of these chemical messengers and cell origins may provide a basis for periodontal repair and regeneration. However, the complete biochemical and molecular changes and the origins of cells, particularly cementoblasts, are not fully understood. It may be argued that periodontal tissue cannot be regenerated (restored to normal architecture), rather it is repaired.2 For example, there is little evidence to support that acellular (primary) cementum reforms. Instead, when repair occurs, cellular cementum is deposited; this is argued to not be a true odontogenic tissue.2 In many regeneration studies, the newly formed cementum is cellular with low numbers of fibers resulting in a new attachment may be weaker than the normal acellular extrinsic fiber cementum.7 Similarly, repair as opposed to complete regeneration of a PDL occurs following damage.8

Gingiva

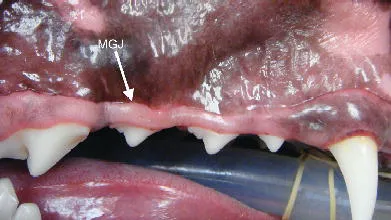

The oral mucosa is classified into specialized mucosa (dorsum of tongue), the non-keratinized alveolar mucosa and the keratinized masticatory mucosa. The masticatory mucosa includes the hard palate mucosa and the gingiva. The gingiva is demarcated from the alveolar mucosa by the mucogingival junction (Figure 1.4).

General histology of the gingiva

A stratified squamous epithelium and deeper connective tissue (collagen fibers and ground substance) are the components of the gingiva. Gingival connective tissue consists of collagen fibers (type I and III collagen), fibroblasts, nerves, blood vessels, lymphatics, macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, T and B lymphocytes, and plasma cells.1,9,10 This connective tissue is called lamina propria with a superficial papillary layer and deeper reticular layer. There are some variations in the lamina propria in relation to the type of gingiva. In the attached gingiva, the lamina propria has a papillary layer interdigitating with rete pegs of the epithelium and a reticular layer adjacent to the periosteum of the alveolar bone.

The keratinocyte is the main cell type of the gingival epithelium.11 The keratinocytes proliferate via mitosis in the basal layer of the epithelium. As cells migrate to the surface epithelium, they differentiate. The keratinization process includes flattening of the cuboidal cells, production of keratohyaline granules, and disappearance of the nucleus. The majority of gingival epithelium is parakeratinized and consists of the stratum basale, stratum spinosum (prickle cell layer), and stratum corneum. Pyknotic nuclei are present in the stratum corneum of parakeratinized epithelium. Non-keratinized epithelium lacks a stratum corneum and stratum granulosum with superficial keratinocytes containing nuclei. Orthokeratinized (complete keratinization with a stratum granulosum) gingiva was not observed in canine gingival samples.12 The epithelial cells of the gingiva have cell-to-cell attachments consisting of desomosomes, adherens junctions, tight junctions, and gap junctions.13

Other cells found in the epithelium include Langerhans cells, Merkel cells, and melanocytes.1,9–11 Melanocytes function to produce melanin granules, thereby providing a barrier to ultraviolet light damage. The melanin granules are phagocytosed and stored by melanophages in the epithelium and connective tissue.10 Melanocytes also function as dendritic cells (antigen-presenting cells). The Langerhans cells are dendritic cells located in the suprabasal layers of the gingival epithelium. They originate from the bone marrow and function as antigen-presenting cells to the lymphocytes. Merkel cells are found in the deep layers of the gingival epithelium and are involved in tactile sensation.

The epithelium is attached to the lamina propria through the basement membrane consisting of the basal lamina (lamina lucida and lamina densa) and reticular lamina. Proteoglycans and laminin are present. Type IV and VII are the major collagens of the basement membrane.14 Hemidesmosomes of the basal epithelial cells attach to the lamina lucida. Clinically, the distinction of the region is important. Mucous membrane pemphigoid cleavage occurs at the basement membrane, resulting in the entire epithelium, including the basal layer, cleaving off the lamina propria, whereas pemphigus vulgaris causes intraepithelial cleavage, leaving basal cells attached to the lamina propria.

Gingival fiber groups

The gingival fiber group is sometimes considered to be part of the periodontal ligament fiber group, which will be discussed later. The collagen fiber bundles of the gingiva are organized into groups (Figure 1.5):6

1. Dentogingival group: Fibers attach cervical cementum to free and attached gingiva. These are the most numerous fibers of the gingiva.

2. Alveologingival group: Fibers attach the alveolar bone to free or...