![]()

Chapter 1

Classical psychometrics

More than a century ago, psychology was defined as the science of human mental manifestations and phenomena. However, it was psychometrics (the science of measuring these mental manifestations and phenomena) that made psychology scientific. Thus, psychometrics is a purely psychological area of research.

From a historical point of view, psychology branched out from philosophy as an independent university discipline at the close of the nineteenth century. It all started in Leipzig in 1879. Here the philosopher Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) established his psychological laboratory at the university. Formally, however, his laboratory remained under the faculty of philosophy. Wundt succeeded in detaching psychology from philosophy, especially freeing it from the influence of Emanuel Kant, an extremely influential philosopher who stated that it is impossible to measure manifestations of the mind in the same way as physical objects (5). With his criticism of pure reason, Kant (1724–1804) established the very important distinction between ‘the essential nature of things’ (things in themselves) and ‘things as they seem’ (i.e., that which we sense or perceive as a phenomenon when faced with the object we are examining).

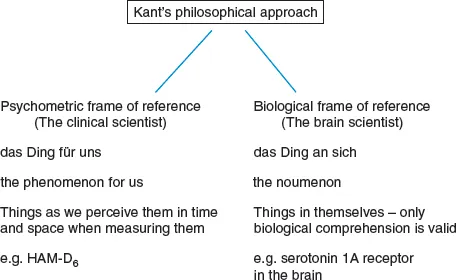

Figure 1.1 illustrates Kant’s philosophical approaches with reference to present day psychiatry, according to which depression is understood to be a clinical phenomenological perception (shared phenomenology of depressive symptoms) as measured by the six depression symptoms contained in the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D6, see Figure 3.1). Modern neuropsychiatry attempts to describe the depression behind the phenomenological perception, i.e., depression ‘in itself’, as we believe it to be present in the brain, for example, as a serotonin 1A receptor problem (impairment).

The area of research now known as brain research is just such an attempt to measure the processes presumed to be taking place in the brain, that is ‘das Ding an sich’. As pointed out by Sontag, reality has increasingly grown to resemble what the camera shows us (6). It is reality itself when the neuropsychiatric camera demonstrates receptor binding in the brain, while clinical reality is increasingly becoming what the camera visualises for us by means of assessment scales or patient-related questionnaires.

The ability to describe reality as it is in itself, i.e., looking at the world unclouded by any preconception of it, has been debated by such neo-Kantentians as Wittgenstein and Quine (7). The quantification of endophenotypes or deep phenotypes is probably the most scientific image of the world. However, we do not have endophenotypes to tell us whether we indeed can describe reality, e.g., the brain, as it is itself. Wittgenstein tells us that he does not want to say whether we can or cannot describe reality as it is in itself. He wanted, as stated by Putman to bring our phenomenological items back to their home in clinical psychiatry. This is what clinical psychometrics is about (7).

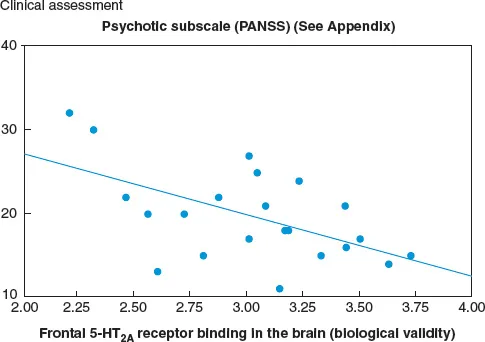

Figure 1.2 shows a correlation between the so-called psychotic symptom items in an American rating scale (see Appendix) and serotonin 2A receptor binding, which it is now possible to measure by means of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning (8). The figure shows a correlation coefficient of −0.57; this is statistically significant but not clinically significant, as the variance on the ordinate axis (the ‘psychosis’ scale) can explain only about 32% of the variance on the axis of abscissas (serotonin 2A receptor binding). If the two patients at the far left are excluded as outliers, then the negative correlation value is halved, so that less than 10% of the variance is explained.

The scale in Figure 1.2 shows the positive symptoms in a schizophrenia scale. In the early 1970s, the American psychiatrist Nancy Andreasen found it important to label those schizophrenic symptoms on which medication had an effect as positive. In clinical psychiatry, these were termed productive symptoms as they were often the reason for hospitalisation in a mental institution. Later on, Nancy Andreasen became interested in neuropsychiatric brain imaging methods [Computer Assisted Tomography (CAT scan), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET)], which became available in the 1980s and 90s. However, in an interview from 2003, she had to admit that schizophrenia is probably not located in one specific section of the brain (9). Schizophrenia affects many different brain areas that cannot be visualised as ‘das Ding an sich’.

Wilhelm Wundt’s major achievement was to realise that mathematical models of ‘das Ding für uns’ can be used to measure the ‘shared phenomenology’ of the state one wishes to assess quantitatively. During his studies at the Heidelberg faculty of medicine, he obtained a degree in medicine. Wundt then participated in studies in the physiology of perception under Helmholtz (1821–94) and Fechner (1801–87). He observed that it was possible to get subjects to reliably assess sensory impressions when the conditions of the study were standardised, e.g., with increasing light or noise exposure.

Wundt’s philosophical basis was that each manifestation of the mind corresponds to a neurobiological substrate in the brain, but in his opinion the psychometric measurement of this manifestation of the mind should only focus on the psychological phenomena (das Ding für sich) and not include any biological elements in any way. He belonged to the branch of philosophy called non-reductive monism (corresponding to Harald Høffding’s critical monism, which maintains that manifestations of the mind cannot be reduced to purely biological variables) (10). On the other hand, it is of course possible to reduce certain manifestations of the mind to less complicated ones in an attempt to obtain the most reliable or objective measure. He felt that it would be possible in this way to make psychology scientific within the frame of its own descriptive realm, since psychological and biological methods of description are two different ways of viewing reality.

Wundt’s approach was that of descriptive psychology where the various dimensions consisting of individual items (symptoms) can be added to give a total score. He was excluding the immediate, peak-experiences detached from relations, e.g., the spontaneous, stimulus-unrelated, perception-like images in the religious experience of the child, actually referred to as ‘Sensus numinis’ (11,12). The clearest description of Wundt’s scientific approach based on his ‘Grundzüge der psychologischen Psychologie’ is found in Vannerus’ monograph (13).

The psychometric method developed by Wundt is probably the only specific psychological method identified in mental science, i.e., in scientific psychology (14). The two most famous scientists to emerge from Wundt’s psychological laboratory in Leipzig were Emil Kraepelin and Charles Spearman; both of them understood that psychological measurement (psychometrics) and biological measurement are two different ways of viewing nature.

Emil Kraepelin: Symptom check list and pharmacopsychology

Kraepelin (1856–1926) had just obtained his medical degree when he applied for a post at Wundt’s laboratory in 1882. As Wundt was unable to finance his salary, Kraepelin also had to take up a post as a locum at the local mental hospital in Leipzig. Thus, Kraepelin held an unsalaried position at the Wundt laboratory. Kraepelin’s purpose was to introduce scientific psychology into psychiatry so that his career as a psychiatrist would be furthered by his studies at Wundt’s psychological laboratory. In his job application to Wundt, he wrote that he would give a kingdom for a [research] topic; Wundt then gave him the opportunity to examine the influence of psychoactive substances such as alcohol and the hypnotic drug chloral hydrate on volunteer research subjects. Kraepelin set out to demonstrate a dose response curve using reaction time measurements as the psychological response and psychoactive substances as the stimuli, so that increasing amounts of alcohol (number of drinks) led to lengthening reaction times. Since Wundt could see that Kraepelin had his heart set on psychiatry, he encouraged Kraepelin to employ this objective scientific method when subsequently assessing the various symptoms presented by patients suffering from mental disorders.

Kraepelin published his first Psychiatric Compendium as early as 1883. In this he attempted to focus on the symptoms presented in the different disorders (Compendium der Psychiatrie. Verlag von Amber Abel, Leipzig, 1883). After leaving the Leipzig laboratory and starting on his career as a psychiatrist in Munich, Kraepelin published several compendiums or textbooks on psychiatry. He revised his textbook almost bi-annually and in the 6th edition in 1899, he was able to describe two disorders with different symptom profiles: manic-depressive disorder and schizophrenia.

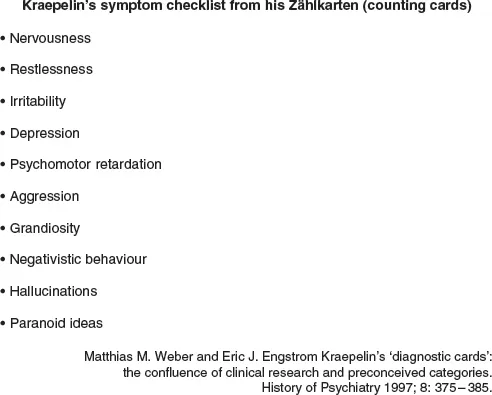

Figure 1.3 shows the checklist Kraepelin used when systematically monitoring his patients over several years in order to ascertain which symptoms possessed ‘shared phenomenology’ over this period of time. These are called checklist symptoms, as Kraepelin only determined whether the symptom was present or absent. This type of scale is called a nominal scale. Using this method, Kraepelin was able to demonstrate that during a period of about six months, some patients presented with the first five or six symptoms in Figure 1.3, while in other episodes of shorter duration (up to three months) they had the next two symptoms (aggression and delusions of grandeur), along with restlessness, sleep disturbance and irritability. Between these episodes of depression or mania, these patients were discharged from hospital and were socially well-functioning. Other patients, who were often lifetime residents in asylums, had the last three symptoms in Figure 1.3. Kraepelin described them as suffering from dementia praecox (now schizophrenia), as the disorder typically started when they were about 20 years of age and was chronic in nature, often with an influence on intellectual functions as well. But these were consequences, not elements, of the schizophrenic symptomatology. Manic-depressive disorder, on the other hand, did not typically emerge at a specific age. Based on the original registrations by Kraepelin on his ‘Zahlkarten’ (counting cards) including the checklist symptoms in Figure 1.3, Jablensky et al made a comparison using the Present State Examination (PSE). From the PSE scores the ICD-9 diagnoses of schizophrenia and manic-depressive disorder can be made. In total Jablensky et al identified 721 patients assessed by Kraepelin and found a concordance for the diagnoses of schizophrenia and manic-depressive disorder of approximately 80% with the ICD-9 diagnoses (15).

In his thesis: ‘Über die Beeinflussung einfacher psychischer Vorgänge durch einige Arzneimittel’ (Jena, Fischer Verlag 1892), Kraepelin established the area of research he designated pharmacopsychology

In the 8th edition of his textbook, written between, 1909–13, Kraepelin added reflections on the psychotherapeutic effects of certain drugs such as morphine, phenemal and chloral hydrate. However, he found that the effects of these drugs on schizophrenia and manic-depressive disorder were extremely poor. He was thus able to observe the spontaneous course of illness in these two disorders.

In the schizophrenic patient, as stated previously, the condition was unremitting, while manic-depressive disorder was characterised by episodes with specific symptoms and then periods between episodes of a year or more in which the patients were completely without symptoms and thus able to function normally. In these descriptions, Kraepelin determinedly avoided including the various theories on disease circulating at that time, such as hereditary elements, stress burden and so on.

Kraepelin’s textbooks were not widely known outside Germany, as the two world wars made German psychiatry less acceptable. His system only began to make an international impact after World War II, not least in the USA.

During his research at Wundt’s Leipzig laboratory, Kraepelin conceived the idea of establishing pharmacopsychology. He thought it important to describe the symptoms found to be reversible during a course of pharmacological therapy. However, as mentioned previously, no therapeutically adequate drugs were developed during Kraepelin’s lifetime, so this research area was scaled down. It is a fact of great interest that Kraepelin was among the first to propose the use of dose response comparisons as an essential pharmacological criterion when determining the clinical effect of a drug.

The Rorschach test

Until the breakthrough of modern psychopharmacology in the 1960s, Danish psychometric research was heavily influenced by the Rorschach Shape Interpretation test, published by the Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921. The Rorschach test consists of 10 symmetrical inkblots, which do not represent recognisable images per se, but are used as indefinite visual stimuli open to many different interpretations, in the same way as with abstract painting. No psychometric theory underlies this ‘inkblot test’, but in the hands of a trained psychologist it may provide an opening for the psychodynamic theories propounded with reference to Freud’s psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis was an accepted method of ...