![]()

Part I

History and Treaties in CBRN - Warfare and Terrorism

![]()

Chapter 1

A Glance Back – Myths and Facts about CBRN Incidents

Andre Richardt and Frank Sabath

In our human history we can find numerous examples of the application of chemical and biological agents used or proposed as weapons during the course of a campaign or battle. In the twentieth century we saw the rise of a new age in battle field tactics and the abuse of detailed scientific knowledge for the employment of chemicals as warfare agents (CWAs). Another step that crossed a border was the use of nuclear bombs against Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945. Although there have been many attempts to ban chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear warfare agents (CBRN agents), their devastating potential makes them still attractive for regular armies as well as for terrorists. Therefore, it is likely that the emergence of CBRN terrorism is going to be a significant threat in the twenty-first century. However, we need to understand our history if we want to find appropriate answers for current and future threats. For this reason, in this chapter we provide a short history of CBRN, from the beginning of the use of CBRN agents up to the emergence of CBRN terrorism and the attempt to ban the use of this threat by negotiation and treaties.

1.1 Introduction

Why do we fear the use of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons? What are the reasons behind the obvious? To answer these questions we have to understand that data and facts are only one part of the story. To understand and to be able to lift the veil of myths about CBRN incidents we need a lot more. Therefore, the history section of this part attempts to lay the basis for a deeper understanding of subsequent chapters.

1.2 History of Chemical Warfare

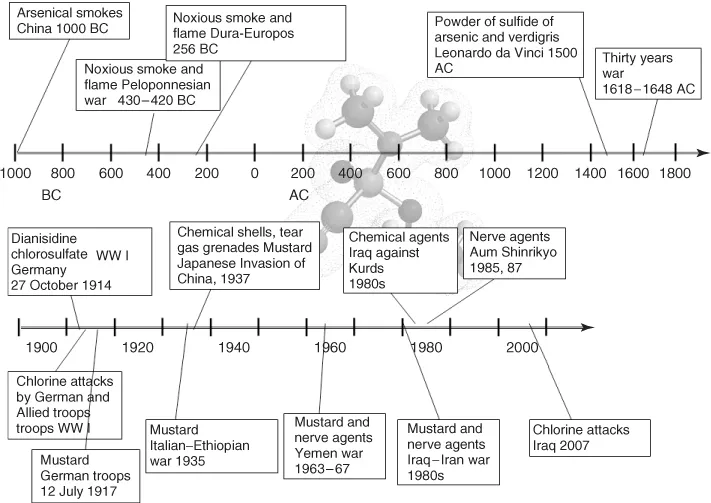

We can find many examples (Figure 1.1) of how the toxic principle of chemical substances has been used to ambush the enemy, even if the exact mechanism was unknown.

- Chemical Warfare Weapon (CWA) “… The term chemical weapon is applied to any toxic chemical or its precursor that can cause death, injury, temporary incapacitation, or sensory irritation through its chemical action …” (http://www.opcw.org/about-chemical-weapons/what-is-a-chemical-weapon/, accessed 26 January 2011)

- Chemical Warfare (CW) Agent “… The toxic component of a chemical weapon is called its “chemical agent.” Based on their mode of action (i.e., the route of penetration and their effect on the human body), chemical agents are commonly divided into several categories: choking, blister, blood, nerve, and riot control agents.” (http://www.opcw.org/about-chemical-weapons/types-of-chemical-agent/, accessed 26 January 2011).

The deployment of toxic smokes and poisoned fire for advantage in skirmishes and on the battlefield was well known by our ancestors [1, 2]. In addition, we can date some significant changes, where the next level was reached in the discovery and use of toxic chemicals (see Figure 1.4 below).

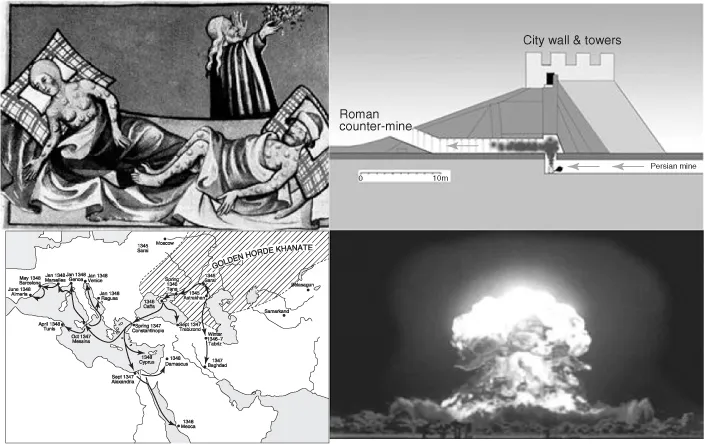

1.2.1 Chemical Warfare Agents in Ancient Times

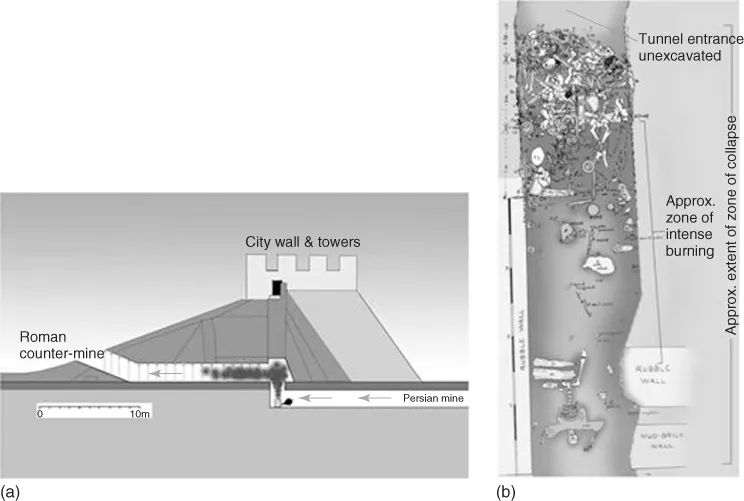

We can date the employment of chemicals as chemical warfare agents (CWAs) from at least 1000 BC when the Chinese used arsenical smokes [1]. By the application of noxious smoke and flame the allies of Sparta took an Athenian-held fort in the Peloponnesian War between 420 and 430 BC. Stink bombs of poisonous smoke and shrapnel were designed by the Chinese, along with a chemical mortar that fired cast-iron stink shells. Other conflicts during succeeding centuries saw the use of smoke and flame. However, it is difficult to confirm historical reports about incidents with chemicals by historical facts. One example of the confirmed use of toxic smoke is the siege of the city Dura-Europos by the army from the Sasanian Persian Empire around AD 256, where poisoned smoke was introduced to break the line of Roman defenders [3]. The full range of ancient siege techniques to break into the city, including mining operations to breach the walls, has been discovered by historians [3]. Roman defenders responded with “counter-mines” to thwart the attackers. In one of these narrow, low galleries a pile of bodies, representing about 20 Roman soldiers still with their arms, was found (Figure 1.2). Findings from the Roman tunnel revealed that the Persians used bitumen and sulfur crystals to start it burning. This confirmed application of poison gas in an ancient siege is an example of the inventiveness of our ancestors.

Toxic smoke projectiles were designed and used during the Thirty Years War (1618–1648). Leonardo da Vinci proposed a powder of arsenic sulfide and verdigris in the fifteenth century. Venice employed unspecified poisons in hollow explosive mortar shells during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Venetians also sent contaminated chests to their enemy to envenom wells, crops, and animals. During the Crimean War (1853–1856), the use of cyanide-filled shells was proposed to break the siege of Sevastopol. However, all these incidents happened without knowing the exact mechanism of poisoning.

1.2.2 Birth of Modern Chemical Warfare Agents and Their Use in World War I

We can date the birth of modern chemical warfare agents (CWAs) to the early twentieth century. Progress in modern inorganic chemistry during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the flowering of organic chemistry worldwide during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries generated renewed interest in chemicals as military weapons. The chemical agents first used in combat during World War I were eighteenth- and nineteenth-century discoveries (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Important Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Discoveries of Toxic Chemicals

| 1774 | Carl Scheele, a Swedish chemist | Discovery of chlorine in 1774. He also determined the properties and composition of hydrogen cyanide in 1782 |

| 1802 | Comte Claude Louis Berthollet, a French chemist | Synthesis of cyanogen chloride |

| 1812 | Sir Humphry Davy, a British chemist | Synthesis of phosgene |

| 1822 | Victor Meyer, a German chemist | Dichloroethyl sulfide (mustard agent) was synthesized in 1822, again in 1854, and finally fully identified in 1886 |

| 1848 | John Stenhouse, a Scottish chemist | Synthesis of chloropicrin |

In 1887, the use of tear agents (lacrimators) for military purposes was considered in Germany. In addition, a rudimentary chemical warfare program was started by the French with the development of a tear gas grenade containing ethyl bromoacetate. Furthermore, there were some discussions in France about the filling of artillery shells with chloropicrin. The French Gendarmerie had successfully employed riot-control agents for civilian crowd control. These agents were also used in small quantities in minor skirmishes against the Germans, but were largely inefficient. In summary, these riot-control agents were the first chemicals applied on a modern battlefield, and the research for more effective agents continued throughout the war.

In the early stages of World War I, the British examined their own chemical technology for battlefield use. Their first investigations also covered tear agents, but later they put their effort towards more toxic chemicals. Nevertheless, the first large-scale employment of chemicals during World War I was initiated by heavily industrialized Germany. Three thousand 105-mm shells filled with dianisidine chlorosulfate, a lung irritant, were fired by the Germans at British troops near Neuve-Chapelle on the 27 October 1914, but with no visible effect [4]. Nonetheless, the British were the victims of the first large-scale chemical projectile attack. The Germans continued firing modified chemical shells with equally unsuccessful results. This lack of success, and the shortage of artillery shells, led to the concept of creating a toxic gas cloud directly from its storage cylinder. This concept was invented by Fritz Haber in Berlin in 1914.

The first great attack with CWAs in modern warfare: Ypres in Belgium. Chlorine attack by German troops in April 1915 [5].

German units placed a total of between 2000 and 6000 cylinders opposite the Allied troops defending the city of Ypres in Belgium. The cylinders contained a total of around 160 tons of chlorine. Once the cylinders were in place, and because of the critical importance of the wind, the Germans waited for the winds to shift to a westerly direction toward the trenches of the Allied troops. During the afternoon of the 22 April 1915 the chlorine gas was released with devastating effects. This attack caused between 800 (realistic) and 5000 (mainly propaganda) deaths.

After the first great attack with chemical warfare agents (CWAs) by German troops near Ypres [5], the Allied troops quickly restored a new front line and it took only a short period of time for them to be able to use chlorine themselves. In September 1915, they launched their own chlorine attack against the Germans at Loos. The expansion of the armamentarium with chloropicrin and phosgene was just the beginning of a deadly competition between both sides [6]. We saw the invention and the development of more protective masks, more dangerous chemicals, and improved delivery systems.

A further step in a devastating chemical war was the use of a new kind of chemical agent. On the 12 July 1917, again near Ypres in Belgium, sulfur mustard was spread by the Germans in an artillery attack. Compared to the first agents, mustard was a more persistent vesicant on the ground, and this caused new problems. Not only was the air poisoned, but the ground and equipment was also contaminated. This new agent was effective in low doses and affected the lungs, the eyes, and also the skin....