This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

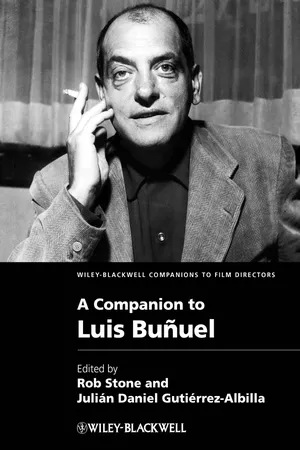

A Companion to Luis Buñuel

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A Companion to Luis Buñuel presents a collection of critical readings by many of the foremost film scholars that examines and reassesses myriad facets of world-renowned filmmaker Luis Buñuel's life, works, and cinematic themes.

- A collection of critical readings that examine and reassess the controversial filmmaker's life, works, and cinematic themes

- Features readings from several of the most highly-regarded experts on the cinema of Buñuel

- Includes a multidisciplinary range of approaches from experts in film studies, Hispanic studies, Surrealism, and theoretical concepts such as those of Gilles Deleuze

- Presents a previously unpublished interview with Luis Buñuel's son, Juan Luis Buñuel

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Luis Buñuel by Rob Stone, Julián Daniel Gutiérrez-Albilla in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

An Aragonese Dog

1

Interview with Juan Luis Buñuel

“I had a long talk with my cousin, Dr. Pedro Cristián García Buñuel, who lives in Zaragoza …” The letter had come in response to a vague attempt to secure permission to reproduce a still from Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1929). Turning the page revealed the signature: Juan Luis Buñuel. The missive continued:

We’ve been discussing all the events of the past year – awards, symposiums, festivals, etc. ad infinitum on my father. We discussed what he would have thought of all this … (he wouldn’t have liked it). It’s like one big recuperation of his work by the official elements of society. As he once told me, “Now that I’m famous, they’re naming streets after me … a few years ago … they would have had me shot!’

So this is the conclusion we’ve come to: we would like the words ME CAGO EN DIOS (I shit on God) to come out, one way or another in the book.

For example: “Luis Buñuel was a very discreet man. He never said ‘me cago en Dios’ in front of nuns or children.”

Or: On the shoot of La Voie lactée, one early morning, he was heard exclaiming, as he bumped his head getting out of a car, “me cago en Dios!” He said it to himself … a quite common Aragonese expression.

It could appear in a small footnote, at the end of the book, or better yet, on the front cover. Up to you. Maybe it’ll shock the Protestant ethic or politically correct readers. Too bad.

So this is the conclusion we’ve come to: we would like the words ME CAGO EN DIOS (I shit on God) to come out, one way or another in the book.

For example: “Luis Buñuel was a very discreet man. He never said ‘me cago en Dios’ in front of nuns or children.”

Or: On the shoot of La Voie lactée, one early morning, he was heard exclaiming, as he bumped his head getting out of a car, “me cago en Dios!” He said it to himself … a quite common Aragonese expression.

It could appear in a small footnote, at the end of the book, or better yet, on the front cover. Up to you. Maybe it’ll shock the Protestant ethic or politically correct readers. Too bad.

Duly cited, correspondence ensued, resulting in a previously unpublished interview at the home of Juan Luis Buñuel (b.1934) in Paris in 2001.

What is your first memory of your father?

My first memory of life and him is when I was barely three years old and I was sitting on his knee by an open window and he was shooting an air pistol at the leaves on a tree. He was teaching me to shoot. That is my first memory.

You moved home a lot when you were a child, didn’t you?

Yes, and then when we lived in California we’d always go out to the desert and be looking under rocks for insects and spiders. But kids don’t like to move. You lose all your friends and have to make new ones. Each time, New York, Los Angeles, Mexico; each time I lost all my friends.

Where was your father happiest?

He liked New York. But he was happiest in Madrid because in Madrid he could go visit his family in Zaragoza. He liked Paris too; Los Angeles less. At the end he wanted to move to Lausanne, where nothing happens. My mother didn’t want that. But my mother had lost all her family by this time and had all her friends in Mexico.

What was family life like?

He was always strict but always cariñoso (affectionate). But always very worried about his kids. That’s what made life difficult sometimes, his fear that something would happen to us.

Were his parents strict with him?

They had servants. He always said his mother didn’t know where the children’s rooms were.

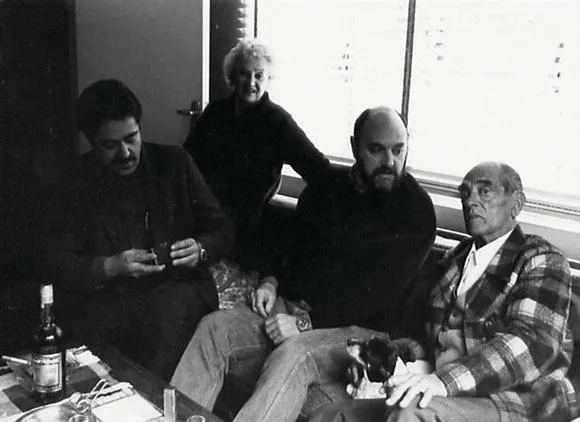

Figure 1.1 Family portrait: (left to right) Rafael, Jeanne, Juan Luis and Luis Buñuel. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

What were his parents like?

His father was a humorous man, constantly joking. His mother was from Calanda and her father was a boticario (chemist). She was completely Semitic Arabic and his father was like a Swede with big grey eyes and almost blond.

What do you remember about growing up in Mexico?

My memories of Mexico and New York are of when all his friends would come over and at suppertime we would eat and then at ten, eleven, twelve o’clock we would sit around and talk. [Imitating his father] “Por el frente de Teruel …” (On the Teruel frontline …). Discussions, always. Always. Whatever country we were in, they’d get together these guys and have these discussions. It was quite a shock for them, being in exile, they needed to try and understand it.

What did exile mean for your father?

We were in Mexico. He didn’t like Mexico, but where else could he go?

In your mother’s book she writes about the house in Mexico becoming a Spain from Spain.

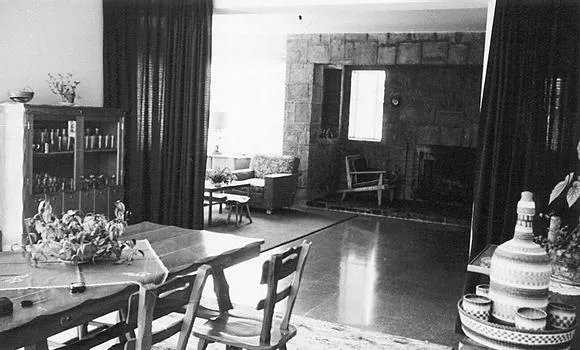

Yes, he built it with an architect from the Residencia [University in Madrid]. It’s not a nice house. There are only two bathrooms and my father’s bathroom is so narrow that if you want to wash your face you have to stand sideways. But in Mexico, if you have a little bit of money, first you have all the servants you want, and we always had very nice ladies to help my mother. So life was fine, but he would make very little money. For Los olvidados he was paid one thousand or two thousand dollars and nothing else. He had to make one or two films a year to just survive. He’d make two films a year that barely covered costs and then he had a little more money so he built the house on Felix Cuevas [street], which is just brick, nothing fancy, but it was always full of friends. When I went to college, he had enough to pay for my college fees and that was it.

Figure 1.2 The house on Felix Cuevas, Mexico City. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

Figure 1.3 The living room of the house on Felix Cuevas. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

You went to a religious school, didn’t you?

Yes, I went to a religious school in Los Angeles. The American school system was so bad they said, “Well, let’s try a Catholic school.” My whole class did their first communion and so I went along with my class and the priest said, “Well, tomorrow you’re going to get the body of Christ and before you come to church tomorrow get your fathers to give you a blessing.” So I tripped up to my father in my white suit for his blessing and he picked me up and said, “If you tell my friends about this, I’ll kill you.” I didn’t understand, but okay, I said I wouldn’t tell anyone.

It must have been difficult for him to send you to a Catholic school.

Well, he appreciated the discipline of the Jesuits. He said, “They taught me discipline and all that but don’t believe a word of the religious part.” Sometimes he’d be at the house and I’d come in and, you know at the end of Tristana, where he’s sitting round with priests and having chocolate? I’d come in and see my father sitting there with four priests and he’d be telling them, “Christo era un majadero” (Christ was a fool). And he’d just play with them.

Were you conscious of being in exile?

I remember when I graduated high school in Mexico and I wanted to go study in America and the American Council called me in and they had this big FBI file on my father. “In 1926 your father went to a meeting of the Left wing …” “But I wasn’t born yet!” “In 1933 …” “I wasn’t born in 1933!” “In 1936 …” “I was two years old!” On and on. And some years later someone sent me the FBI file and most of it was deleted.

This file would have been produced in collaboration with Spanish authorities?

Probably. And here too in France. Because he had problems everywhere. He had problems here when L’Âge d’or came out. And Salvador Dalí was also a son of a bitch.

Your father never forgave Dalí, did he?

No, he didn’t. No one who says it’s good that Federico García Lorca got killed and that Franco won the war was going to keep his friends. Dalí had written many times to my father saying, “I have a great idea for a new film.” But no, they never met again.

Your father didn’t get on with Gala.

No, he told me once he tried to kill her. He jumped on her, was choking her and he told me that what he wanted was to see her tongue appear between her teeth.

Did he talk to you much about his time as a student in Madrid?

Yes. You know, they always look so serious in photographs, but they were fuck-offs, always laughing, always playing jokes on each other. People take him too seriously. I think he enjoyed laughing more than anything.

Did he ever talk to you about Lorca?

Yes, sometimes I’d see him sad and ask what’s the matter? And he said, “I was thinking of Lorca, his finesse, and thinking of when they were making him walk, him knowing that they were going to shoot him, it makes me so sad.” But my father was strange. He’d say, “I never knew Lorca was homosexual.” And once he was furious: “Federico, come here, they tell me you’re a fag!” And then he said, “My god, it’s true.” He didn’t know. But that didn’t change his feelings towards him. Thanks to Federico his whole world opened up. My father was un bruto (a brute) from Aragón who liked to box. And Lorca opened up the world of poetry and music to him. But he didn’t like Lorca’s poetry very much. He always said the greatness of Lorca was himself, his personality, his cariño (affectionate nature), which was extraordinary.

Figure 1.4 Toledo. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

Did he tell you many stories of his student days?

This one time we were in Toledo walking around and having drinks and it got late and we got way up to the top of Toledo and there was this balcony with the Tajo [river] way down below and he got sad and I said, “What’s the matter?” And he said, “We used to come up here, Federico, Salvador and I … to vomit after we’d drunk too much. Just to see the vomit hit the Tajo. He said they’d drink a lot of cheap anise and then go to Mass and then confession stinking of anise and say, “Father, I want to join the order!” “Well,” said the priest, “come back in a few hours.”

Was he a good student?

Yes, he read constantly, constantly. He would read and reread. But the Belgian writer who writes detective stories, Georges Simenon, was his favorite. We had the whole collection of Simenon.

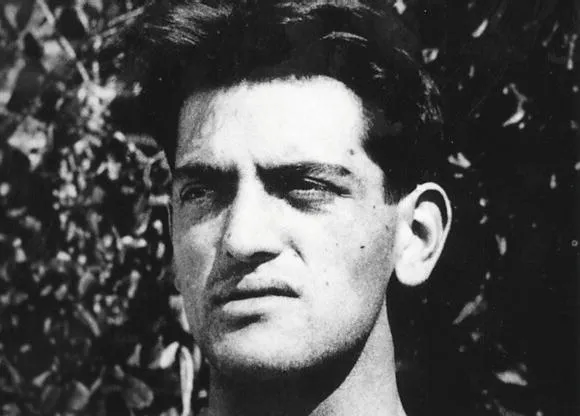

Wasn’t he also a champion boxer?

No. He boxed but I think they hit him on the nose and he quit.

What else did he like?

He knew a lot about art but he didn’t like paintings very much. He hated museums. I remember once we were in Madrid and bored and I said, “Let’s go to the Prado [Museum].” “Bad idea,” he said, “thirty years and I’ve never been to the Prado.” But we went and we rushed to see The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch. “Magnífico!” he cried, “Vámonos!” (Magnificent! Let’s go!). We went to a bar and that was that. He told me once he went to the Picasso museum here in Paris and he starts walking through it and then starts running and by the end he’s running so fast he bursts through the door screaming and the museum people run after him and say, “What’s the matter?” And he says “Ah, I’m bored shitless!” Really, the only paintings we had in the house [in Mexico] were because I insisted because the walls were so bleak. He didn’t like paintings because spiders could hide behind paintings.

Figure 1.5 Luis Buñuel in his boxing days. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

He didn’t like spiders?

Oh, no. That’s a family obsession. I have a cousin who sees a spider, he faints. Big guy.

And your father was the same?

Yes. The first time I went to Zaragoza, I was twenty-three and it was Christmas time and we had that night of Christmas dinner with the whole family and my cousin said, “Watch and see what happens at midnight, when you have cognac and sit around, just watch what happens.” Two uncles, three aunts, all sitting around and one of my aunts says, “Guess what I saw yesterday?” “Yes, what was it?” “A spider the size of a potato!” And then they’d all be talking about spiders for three hours. My cousin said, “Every Christmas time this happens. It’s tradition.”

Figure 1.6 Buñuel with his sisters. Courtesy of the Filmoteca Española.

But your father studied entomology, didn’t he?

Yes, and he loved spiders. He was fascinated by them. Once in Mexico, I put a spider on the wall of the breakfast room. He’d get up at six, come down and have his coffee and I put this tiny little spider on the wall and at six-thirty: “Qué nadie se mueva!” (Nobody move!) Bang, crash, bang! Then he laughed. He saw it was a rubber one.

But in The Young One he has the scene where the girl stamps on a tarantula. He must have hated filming that.

Oh, he hated to kill any animal. Although, to be fair, he killed a lot of animals in his films. The first was in Las Hurdes, where he shoots the goat and people said, “Why did you shoot the goat?” Now goats fall and get killed. You can be with your camera waiting, but it can be ten or fifteen years. So you shoot a goat. Every day they kill goats for the market, so instead of cutting its throat you put a bullet through him. The wind was blowing this way so it blew the smoke across the camera. But anyway, they bought a goat set it up there and shot it.

They bought it? It wasn’t a wild one?

No, wild goats don’t let you get that close with the camera. He was honest. He just recreated the scene.

Do you think he would have liked to have fought in the Spanish Civil War?

No, I don’t think so. I don’t think he was physical in that sense. No, I don’t think he would have been a soldier. That wasn’t his strength. His strength was in other things. He got very nervous in May ’68.

You were both here in Paris, yes? He writes in My Last Sigh that he was worried about you. He says [director] Louis Malle gave you a gun and taught you to shoot it.

Oh, I had guns. I still have guns. My whole family were gun-crazy. So we had seventy pistols. All my family had guns. My uncles, my cousins were all gun crazy. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: An Aragonese Dog

- Part Two: A Golden Age

- Part Three: The Forgotten One

- Part Four: Strange Passions

- Part Five: An Exterminating Angel

- Part Six: Discretion and Desire

- Part Seven: And in the Spring

- Filmography

- Index