This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers students a concise and clearly written overview of the events of the Haitian Revolution, from the slave uprising in the French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1791 to the declaration of Haiti's independence in 1804.

- Draws on the latest scholarship in the field as well as the author's original research

- Offers a valuable resource for those studying independence movements in Latin America, the history of the Atlantic World, the history of the African diaspora, and the age of the American and French revolutions

- Written by an expert on both the French and Haitian revolutions to offer a balanced view

- Presents a chronological, yet thematic, account of the complex historical contexts that produced and shaped the Haitian Revolution

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution by Jeremy D. Popkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Colonial Society in a Revolutionary Era

The beginning of the Haitian Revolution in August 1791 shocked the entire Atlantic world because it occurred, not in some remote backwater of the Americas, but in the fastest-growing and most prosperous of all the New World colonies. By 1791 Europeans had been staking out territory across in the Atlantic and importing African slaves to work for them for 300 years, but nowhere else had this colonial system been made to function as successfully as in Saint-Domingue. In the twenty-eight years since the end of the eighteenth century’s largest conflict, the Seven Years War, in 1763, the population of the French colony had nearly doubled as plantation-owners cashed in on Europe’s seemingly unquenchable appetite for sugar and coffee. Imports of slaves to the island averaged over 15,000 a year in the late 1760s; after an interruption caused by the American War of Independence, they soared to nearly 30,000 in the late 1780s. Nowhere else had slaveowners learned to exploit their workforce with such harsh efficiency: by 1789, there were nearly twelve black slaves for every white inhabitant, and the wealthiest Saint-Domingue plantation-owners were far richer than Virginians like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Cap Français, the colony’s largest city, was one of the New World’s busiest ports; on an average day, more than a hundred merchant ships lay at anchor in its broad harbor. The city itself, with its geometrically laid-out streets and its modern public buildings, was a symbol of European civilization in the tropics.

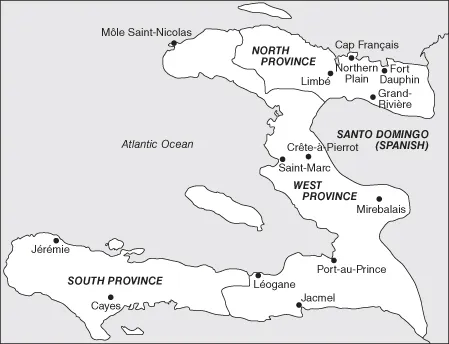

Map 2 The French Colony of Saint-Domingue in 1789.

Source: Adapted from Jeremy Popkin, Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Uprising (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

The Origins of Saint-Domingue

The island of Hispaniola, where Saint-Domingue was located, had been the site of one of the first contacts between Europeans and the peoples of the Americas: Columbus landed on its northern coast during his first voyage in 1492. The Spanish made it the first hub of their empire in the New World; the diseases they brought with them and their harsh exploitation of the population soon killed off the native Taino Indians. By the end of the 1500s, however, the Spanish had found richer opportunities for settlement in Mexico, Peru, and other parts of the Americas. Lacking gold and other easily exploitable resources, Hispaniola was virtually abandoned. During the early decades of the 1600s, the English, French, and Dutch, shut out of the scramble for territories in the New World by the first arrivals, the Spanish and the Portuguese, began staking claims to some of the islands in the Caribbean. France established its first permanent colonial settlement on the small island of Saint-Christophe in 1626; in 1635, the French planted their flag on two larger islands in the eastern Caribbean, Martinique and Guadeloupe. Together with a small colony on the coast of South America – today’s French Guyana – and their outposts in Canada, these islands became the base of France’s overseas empire. In the same period, small groups of seagoing adventurers, acting on their own, landed on the northern coast of Hispaniola. These early settlers, not all of them French, were known as boucaniers or buccaneers because of the boucans or open fires on which they smoked meat from the wild cattle and hogs they found roaming the deserted island.

Eager to expand their colonial domains at the expense of their long-time enemies, the Spanish, the French made a move to claim territory in Hispaniola by appointing a governor for the boucaniers’ settlements in 1665. In 1697, at the end of the European conflict known as the War of the League of Augsburg, Spain officially ceded the western third of the island to Louis XIV; the remainder of the island became the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo. By this time, Europeans all across the Caribbean had realized the enormous profits to be made by establishing plantations to grow sugar. The sugar boom first took hold in some of the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean, such as the British colony of Barbados and the French island of Martinique. By 1700, however, much of the suitable land on those islands had already been used up. Saint-Domingue, a larger colony, offered new horizons for sugar production, and an ever-increasing stream of immigrants, dreaming of wealth, arrived on its shores. In 1687, there were just 4,411 whites and 3,358 black slaves in Saint-Domingue; by 1715, the figures were 6,668 whites and 35,451 slaves, and in 1730 the slave population had risen to 79,545. Forty years later, in 1779, there were 32,650 whites and 249,098 slaves, a figure that would nearly double by the end of the 1780s.1

The geography of Saint-Domingue dictated its pattern of settlement. Sugar plantations needed flat, well-watered land; colonists rapidly staked out claims in the plain in the northern part of the island and later in the drier valleys between the steep mountain ranges in the west, where irrigation systems had to be built to make sugar-growing possible. The long southern peninsula of the island was the last part of the territory to be settled; harder to reach from France than the other parts of the colony, it was more involved in contraband trade with the British, Dutch, and Spanish colonies to its south and west. Eventually, the French administration divided Saint-Domingue into separate North, West and South provinces. Cap Français in the north and Port-au-Prince in the west were the main administrative centers; smaller cities such as Cayes, the capital of the South Province, were scattered along the coast, at points where ships could anchor and collect the products of the plantations for transport to Europe. By the mid-1700s, Saint-Domingue plantation-owners had discovered a new cash crop, almost as lucrative as sugar: coffee. Coffee trees could be grown on the slopes of the island’s steep mountains, on land that was unsuitable for sugar cane. Whereas sugar plantations required large investments of money to pay for the expensive machinery needed to crush the canes, boil their juice, and refine the raw sugar, coffee plantations were cheaper to set up and attracted many of the new colonists who arrived after 1763. Indigo, grown to make a blue dye widely used in European textile manufacturing, was another resource for small-scale plantations, and, by the end of the century, cotton-growing was also becoming an important part of the colony’s economy. In 1789 there were some 730 sugar plantations in the colony, along with over 3,000 plantations growing coffee and an equal number devoted to indigo.

In the early days of colonization, the labor force in the French islands included both white indentured servants and black slaves. As the sugar boom created a growing demand for workers, however, plantation-owners throughout the Caribbean became more and more dependent on Africans to work their fields. After the end of Louis XIV’s long series of wars in 1713, the French slave trade expanded rapidly. Throughout the eighteenth century, slave ships left the ports on France’s Atlantic coast, carrying trade goods to the coast of Africa. There, they exchanged textiles, muskets, and jewelry for black men and women, often captives taken in wars between rival African states. Packed into the holds of overcrowded vessels, the terrified blacks knew only that they would never see their families and homelands again. Close to a sixth of the slaves on a typical voyage died from disease or mistreatment before reaching the Americas. Those who arrived in Saint-Domingue were promptly put up for sale and found themselves taken off to plantations where, if they were lucky, they might encounter a few fellow captives who spoke their native language. In this strange new world, they had to struggle to make some kind of life for themselves, under the control of masters whose only interest was in extracting the maximum amount of useful labor from them.

A Slave Society

Eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue was a classic example of what historians call a “slave society,” one in which the institution of slavery was central to every aspect of life, in contrast to “societies with slaves,” in which slaves were a relatively small part of the population and most economic activity was carried on by free people. Organized in work gangs or atteliers, slaves in Saint-Domingue performed almost all of the exhausting physical labor on which the growing and processing of sugar and coffee depended. Much of the field work – hoeing fields to clear away weeds, planting, and harvesting – was done by women; slave men were often trained to do more skilled jobs, such as sugar-processing, carpentry, or, like the future Toussaint Louverture, serving as coachmen. Children were assigned to a special petit attelier as early as possible, to accustom them to work, and slaves too old or sick to toil in the fields were used to guard the plantation’s animals or its storeroom. At the top of the hierarchy among the slaves were the commandeurs or slave drivers, who directed the other slaves’ work. The smooth functioning of a plantation depended on the commandeurs: even though the commandeurs were slaves themselves, plantation-owners and managers treated them with respect to maintain their authority over the rest of the workforce. While most plantation slaves worked in the fields or processed sugar and coffee, some were used as domestic servants for the masters and their families. The one skilled job usually reserved for women was the direction of the infirmary; supervising the care of the sick and ferreting out malingerers who were trying to escape work was an important task in the overall management of a plantation.

Caribbean sugar plantations were notorious for the demands they placed on their slaves (see Figure 1.1). A French observer in the 1780s described the scene he witnessed in Saint-Domingue’s sugar fields: “The sun blazed down on [the slaves’] heads; sweat poured from all parts of their bodies. Their limbs, heavy from the heat, tired by the weight of their hoes and the resistance of heavy soil, which was hardened to the point where it broke the tools, nonetheless struggled to overcome all obstacles. They worked in glum silence; all their faces showed their misery.”2 Sugar cane had to be processed as soon as it was cut, before the precious juice began to turn to starch and lose its sweetness. During the long harvesting season, from January to July every year, cane was cut in the fields and immediately fed through the heavy rollers of the crushing machine. The extracted juice then had to be boiled for hours in large cauldrons, while slaves stirred the syrup in the sweltering heat; it was then poured into molds so that the sugar could crystallize. Slaves who had toiled in the fields during the day were forced to work long into the night, and accidents caused by exhaustion were frequent; slave women who had to feed the cane stalks into crushing machines often lost arms that got caught in the machinery. Work on coffee plantations was not driven by the same need for haste as that involved in sugar production, but the endless routine of planting and caring for the trees, harvesting the beans, spreading them out to dry in the sun, and processing them kept slaves equally busy. In addition to working for their masters, slaves were responsible for producing most of their own food: masters usually gave them small private plots to raise yams, beans, and other vegetables for themselves. In theory, slaves were supposed to be guaranteed one day a week to cultivate these gardens, but masters never hesitated to commandeer them for other tasks; the slaves had to make do with whatever free time they could find to tend their crops.

Figure 1.1 Plantations and slave labor. Illustrations to the French Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia) of the mid-eighteenth century treated black slavery as a normal aspect of economic life, although other articles in this compendium of Enlightenment thought raised some questions about the institution. The upper illustration here shows blacks harvesting cotton and preparing it for shipment to Europe. Slave huts are clearly visible on the right in the depiction of a sugar plantation (below), even though slaves themselves are not shown in the picture.

Source: Copper engraving from D. Diderot, Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire des sciences. Photo: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale / AKG-images.

Living conditions for plantation slaves were harsh. Although Europeans considered blacks uniquely suited to work in the hot Caribbean climate because it resembled the weather in Africa, newly arrived slaves fell victim to unfamiliar diseases in their new environment or succumbed to depression resulting from the traumatic ordeal they had been through; as many as a third of the slaves died in their first year in the colonies. The average life expectancy of a slave after arriving in Saint-Domingue was no more than seven to ten years. Most slaves suffered from chronic malnutrition: the system of private plots rarely sufficed to provide enough food, and above all slaves were deprived of meat, a basic element of their diet in Africa. Slaveowners were theoretically obliged to supply their slaves with adequate clothing, but few of them paid attention to this rule, and slaves often had only rags to wear or were forced to go around half-naked. Left to themselves, slaves tried to build huts similar to those familiar to them from Africa, but masters often preferred to force them to live in larger buildings where they had less privacy and could be supervised more easily. Masters discouraged marriages among their slaves, for fear that having their own families would give them a sense of independence. Newly arrived slaves, called bossales, were sometimes put under the supervision of blacks who spoke their native language, but they still had to learn Creole, a combination of elements of French and various African languages that served as the general medium of communication in the colony. At the time of the revolution, African-born bossales made up at least half of the Saint-Domingue population. Many of the newly arrived slaves at the time of the revolution had military experience, having been taken captive in wars in the Congo region of Africa; they would make an important contribution to the uprising that began in 1791.3 Masters considered slaves born in the colony, known as creoles, easier to manage than the bossales; the creole slaves grew up speaking the local language and had never known any life outside of the slave system.

Hanging over the slaves at all times was the threat of brutal physical punishment if they angered their masters. Slaveowners and their hired managers routinely whipped slaves to force them to work and to punish them for any sign of insubordination. To make it easier to identify them if they tried to run away, slaves were branded with their owners’ initials or other marks. Those who were caught after escaping were often forced to wear chains or iron collars, and might be shackled to a post at night. Masters were also legally permitted to cut off disobedient slaves’ ears or to cut their hamstrings as punishment. Slaveowners often built private prisons or cachots, where slaves were locked up in the dark for various offenses. In theory, masters were not supposed to execute their slaves, but in practice the authorities rarely intervened to protect them. In 1788, charges were brought against a Saint-Domingue master named Lejeune, who had tortured two slave women to death because he suspected them of poisoning other slaves on his plantation. Although Lejeune was initially convicted, other slaveowners protested so vocally against the verdict that it was overturned.

In theory, the treatment of slaves was regulated by the Code noir or “Black Code” issued in 1685 by the French king Louis XIV. The Code noir provided a legal basis for slavery in the French colonies, even though the institution was officially barred from the metropole where French judges had laid down the principle that “there are no slaves in France” in 1571. Although the Code noir was meant to uphold the authority of slaveowners over their human property, it did include some provisions meant to prevent the worst abuses of slavery. Masters were made responsible for providing their slaves with adequate rations, they were supposed to furnish them with two new sets of clothing every year, and they were encouraged to provide for their education in the Christian religion. In extreme circumstances, the code permitted slaves to appeal to the royal authorities for protection from their masters. In practice, however, both colonial plantation-owners and French administrators ignored these clauses of the code: slaves were left to furnish most of their own food, clothing was distributed erratically, and little effort was made to Christianize the slaves, for fear that this would require recognizing that they had at least some minimal rights. Few slaves even knew...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Viewpoints/Puntos de Vista: Themes and Interpretations in Latin American History

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Illustrations

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Introduction

- 1 A Colonial Society in a Revolutionary Era

- 2 The Uprisings, 1791–1793

- 3 Republican Emancipation in Saint-Domingue, 1793–1798

- 4 Toussaint Louverture in Power, 1798–1801

- 5 The Struggle for Independence, 1802–1806

- 6 Consolidating Independence in a Hostile World

- Afterword: The Earthquake Crisis of 2010 and the Haitian Revolution

- Recent Scholarship on the Haitian Revolution

- Index