![]()

Chapter 1

What Is Beauty?

Steven A. Guttenberg DDS, MD

Perhaps the British novelist, essayist, and poet D. H. Lawrence had it right when he proffered that “Beauty is an experience, nothing else. It is not a fixed pattern or an arrangement of features. It is something felt, a glow or a communicated sense of fineness.”

For beauty, as we have come to understand it, is merely a perception of appearance by ones self or by another. It is subjective and differs among individuals and between cultures. Certainly, that which is considered beautiful among Aborigines may not be interpreted similarly by others around. Although the phrase is frequently ascribed to others, the author Margaret Wolfe Hungerford in 1878 was the first to write in her novel, Molly Bawn, the famous idiom that “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Certainly her proffer seems on point.

One’s perception of beauty varies from generation to generation. For example, the proportions and shape of the “sought after” nose in America today is far different than the cute, little upturned (bobbed) nose popular in the early and mid-1900s. If one peruses old books and magazines, clearly the same is true of body morphology and even hairstyles.

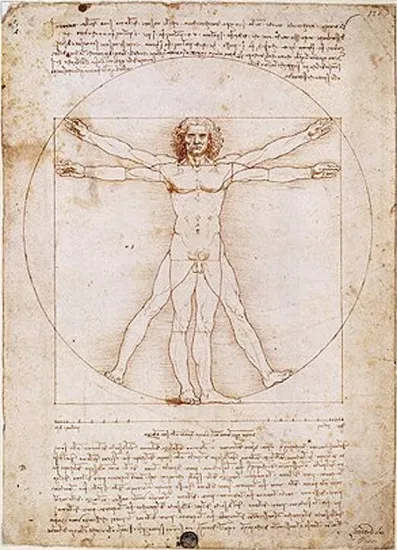

However accurate they may be, we as doctors do not depend on romantic notions or assertions to define concepts, even one as nebulous as beauty. We look to norms, ratios, mathematical formulae, and science as did Leonardo da Vinci in his famous drawing, the Vitruvian Man (Figure 1.1).

Regardless of cultural or temporal differences, the face is ordinarily the first thing that we see when we come upon another person and form our initial impressions. That appearance is the focal point of an individual since it is usually the most exposed body part for one to quickly formulate and extrapolate a subjective interpretation of that person’s substance. For example, good-looking people are assumed to be more intelligent, have better personalities, and to be sexually warmer than those who are not. This phenomenon, although not universally accepted, is frequently referred to as the halo effect. The opposite can also be experienced. The negative halo effect refers to an unfavorable impression that is attached to those less attractive. It is no wonder that Americans spend billions of dollars annually to attempt to improve their looks.

Cultural differences aside, there are certain components of what is considered an attractive face that seem to be universal.

Symmetry is one. Studies have shown that even infants, who clearly have no training or cultural input into what is considered attractive, routinely focus on those with symmetrical faces rather than those with asymmetries even if they are not looking at a parent. Whereas minor asymmetries are often overlooked, more significant ones can detract significantly from a person’s appearance. Think of an individual with a crooked smile or nose or a marked difference in orbital size.

Another component in judging an individual’s looks is a matter of proportion. For example, if someone has a large facial skeleton, you will not be surprised or put off if they have a large nose. But if that same nose is attached to a patient with a small face, it attracts negative attention. Sometimes the nose is appropriately proportioned for the face, but looks outsized because the maxilla is retrusive. Observers similarly evaluate the eyes, ears, and jaws as they size up one another.

In addition to assessing the symmetry of facial features, one also subliminally and quickly appraises the placement of those components to see if they are where they should be. Individuals with hypo- or hypertelorism are easily noted, even by the casual observer. Perhaps subtler placement aberrations can be appreciated in patients who have abnormalities of the horizontal facial thirds or vertical facial fifths. These alterations can also diminish one’s subjective beauty rating.

While symmetry, placement, and proportion are important signposts of beauty, all of the facial components contribute to the overall look. We virtually instantaneously assess a person’s appearance, looking at the features mentioned above in addition to the individual components of their eyes, nose, smile, teeth, lips, hair, and of course, the quality of their skin. When it comes to correcting shortcomings in this area there are numerous overlapping dental and medical specialists who would lay claim to all or part of the face.

All in all, facial beauty is not just about an ear or an eye or a nose and so on. It is the sum of everything between the clavicles and the top of head including the enveloping skin and hair, which is why this text is so unique and important. Experienced practitioners from seven different specialties, all focused on the appearance of the mouth, face, and jaws have contributed to this volume: cosmetic dentistry, prosthetic dentistry, oral and maxillofacial surgery, dermatology, facial plastic surgery, plastic surgery, hair restoration, and oculoplastic surgery.

What lies here before you is a primer for students of dentistry and medicine, residents and fellows, as well as seasoned practitioners seeking to enhance their skills. It is hoped that no matter what your background, you will find pearls in these pages to apply to your practice.

![]()

Chapter 2

Smile Design and Veneers

Peter Rinaldi DMD

Introduction

Beginning in the early in the 1990s, the smile slowly became an integral part of the total facial complex. The aesthetic appeal of a “Hollywood” smile started to surface as an important asset to a patient’s overall looks and appeal. Today there is a legitimate marriage between the creation of aesthetic facial and dental components to create a person’s look. The dentofacial relationship should be greatly considered when improving a patient’s appearance. Plainly stated, the entire aesthetic concerns, both facial and oral, need to be evaluated and addressed.

The challenge of combining the triad of phonetics, function, and aesthetics has always been the primary restorative goal of dentists. As the cosmetic savvy of patients increases, there becomes a demand to look at all of the aesthetic aspects that can be improved for a particular patient.

Understanding what a patient likes and dislikes about their appearance will help create a much better outcome. Oftentimes, the patient does not know what he or she is displeased about. It is up to the clinician to educate and guide the patient. To properly accomplish that, the clinician must be aware of all the treatment modalities that are available.

Aesthetic improvement procedures in plastic surgery, dermatology, and dentistry are in high demand by the populace and are within themselves interactive. Age-related changes in an individual’s appearance have become the key driving force for cosmetic enhancement (Figure 2.1).

Cosmetic dentistry has grown tremendously from its inception. Although it was always the objective of dentists to restore teeth to their natural form, treating the dentition for purely aesthetic reasons began to develop and evolve with the discovery of both enamel and dentin bonding agents and the ability to etch porcelain. Prior to the modern era of bonding, Dr. Charles Pincus would attach specially made pieces of acrylic to an actor’s own dentition to improve their smile.1 Although not functional in nature, these early laminates did provide an improved aesthetic look. The dentist’s knowledge of the relationship between the gingival tissues, teeth, and the perioral area as related to aesthetics has vastly increased since this early beginning.

This expansion of cosmetic understanding by dentists was paralleled by the growth in the number of patients who became aware of what is considered to be a pleasing smile. Many Americans feel that a healthy, attractive smile is an important social asset. A survey performed by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry revealed that more than 87% of adults feel that an unattractive smile can impede career success. In addition, 92% of the respondents said that an attractive smile is an important social asset.2

In a population where 50% of individuals are unhappy with their smiles, addressing this concern is a matter of importance. Even young people of today have an opinion about what a nice smile demonstrates. Teenage girls in the United Kingdom were asked to assess models in girl magazines. Models that appeared to be “cool” and “desirable” were deemed not to need orthodontic treatment.3 Although the dentist is the person that will deliver the restorative treatment, it is the responsibility of all health-care professionals who practice cosmetic procedures to recognize the importance of orodental aesthetics when rejuvenating and enhancing a person’s overall appearance.

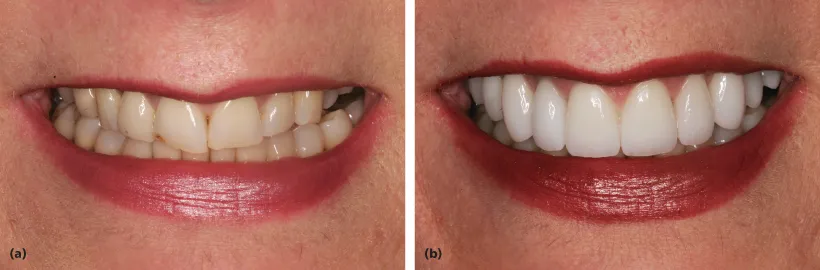

The term smile makeover has become well infused into the vocabulary of our society. As a play on the facelift, the smile lift became a new concept in aesthetic dental care.4 Smigel described the nonsurgical facelift5 (Figure 2.2).

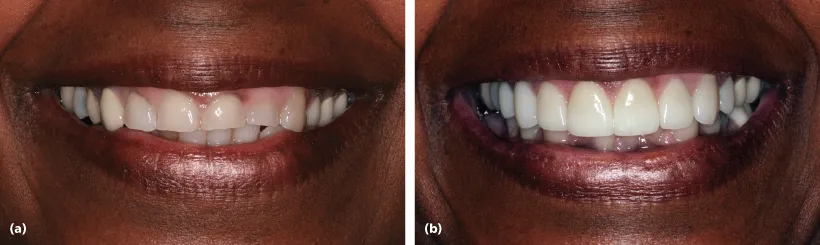

It represents an overall tooth-to-tooth, tooth-to-gums, tooth-to-lips, and tooth-to-face relationship. Smile makeovers are performed to improve the aesthetics of teeth not in balance and harmony. They could also be an attempt to rejuvenate smiles that have degenerated over the years through wear and tear (Figure 2.3).

The type of treatment that encompasses a smile makeover could be as simple as tooth bleaching to the complexity of a full mouth reconstruction. In the end, the treatment must fulfill both functional and aesthetic components. It can be said that good function will promote good aesthetics and vice versa. However, this does not mean that a smile that is unattractive does not function properly. The clinician must be fully aware that elective procedures should maintain or improve function, not impair it.

Teeth that have a dark shade, are creamy yellow, brown, gray, or a combination of these colors can create an unsightly smile. These color changes can occur slowly over many years as microporosities in enamel pick up staining from ingested food and drink, chemical exposure, or smoking. In addition, the discoloration can occur hereditarily. The ingestion of certain antibiotics (most notably tetracycline-containing medications) during the formative years of permanent tooth structure can cause teeth to turn gray-brown and sometimes have a petrified wood appearance. High levels of fluoride ingestion, usually from a water supply that is naturally fluoridated, can cause fluorosis, a condition in which the teeth may demonstrate unattractive white or brown mottled spots. Furthermore, dental discoloration can occur after trauma or secondary to endodontic tre...