This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dictatorship in South America

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Dictatorship in South America explores the experiences of Brazilian, Argentine and Chilean experience under military rule.

- Presents a single-volume thematic study that explores experiences with dictatorship as well as their social and historical contexts in Latin America

- Examines at the ideological and economic crossroads that brought Argentina, Brazil and Chile under the thrall of military dictatorship

- Draws on recent historiographical currents from Latin America to read these regimes as radically ideological and inherently unstable

- Makes a close reading of the economic trajectory from dependency to development and democratization and neoliberal reform in language that is accessible to general readers

- Offers a lively and readable narrative that brings popular perspectives to bear on national histories

Selected as a 2014 Outstanding Academic Title by CHOICE

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dictatorship in South America by Jerry Dávila in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Dependency, Development, and Liberation

Latin America in the Cold War

How does a country develop? Is economic development simply created by a free marketplace? Or is it possible to accelerate development by guiding the market? If so, how can a government engineer that development? In the twentieth century, these were among the most pressing questions facing Latin America, and the answers to them had enormous consequences.

At the beginning of the century, liberalism was the predominant political and economic ideology in Latin America. It entailed constitutional republican government whose role was to preserve order, protect private property, and promote free trade. In practice, this meant that a handful of people controlled farmland, mines, mills, and the labor to exploit them. This minority profited by exporting agricultural commodities and minerals, while importing manufactured goods. It was a system that placed great wealth in a few hands, and its critical integer was cheap labor. The patrons of the economic system were also the directors of the political system.

By the middle decades of the century, social groups including women, urban workers, and rural laborers, pressed for political and economic inclusion. At the same time, Latin Americans began to ask whether it was possible to catch up with wealthy, powerful, and industrialized nations like the United States, Britain, Germany, or Japan. The dual impulses of political inclusion and economic growth were interrelated, and a new kind of politician, populists, learned to tap the groundswell of new voters and the appeal of economic development. Populist politicians cultivated a mass following by promising rights to workers, access to health and education, industrialization, and rising wages. In Brazil, Getúlio Vargas played this role in the 1950s, building on the base of labor legislation and state sanctioned unions he created during 15 years of mostly dictatorial rule (1930–45). Argentina had one of the most charismatic populists, Juan Perón (1946–55). Chile, by contrast, had little populist experience because traditional political parties expanded their appeal to workers, producing electoral competition between its center Christian Democratic Party and leftist groups like the Socialist Party, which culminated in the presidential election of Salvador Allende (1970–3).

By the end of the Second World War, Latin Americans faced a transcendent question: what is the path to development? And this question begat two difficult ones: Who bears the costs? And who reaps the rewards? The answers to the first question reflected a broad consensus: the state must act where the market had failed to propel economic development. But the second set of questions were divisive: any development plan confronted the gulf between those who traditionally held wealth and political power, and those who did not.

What did development mean? It was the response to underdevelopment, which had many facets. Economically, underdevelopment meant reliance on export agriculture sustained by impoverished rural laborers, as well as reliance on imported technology, manufactured goods, and capital. It also meant deficient infrastructure. Take Brazil as an example: much of its territory was unreachable by road. Its rail lines and highways were inadequate and badly conserved. The reach of electricity, telephone, telegraph, as well as water and sewer treatment was restricted to urban areas in a country where the majority of the national territory and population were rural. Politically and socially, it meant weak institutions with a limited reach. Education and access to healthcare were restricted: in 1950, 57% of Brazilians were illiterate (and consequently lacked the right to vote). The armed forces lacked capacity, training, and equipment. Adding to these challenges, Brazil’s population was exploding: Of 52 million inhabitants in 1950, more than half were under the age of 20.

“Developmentalism” was the art of correcting underdevelopment. Among 1950s U.S. intellectuals, modernization theory was an especially influential vision of development which was based on the assumption that underdeveloped societies faced a lag relative to developed societies. It presumed a linear path of evolution in which the United States sat hierarchically above Latin America. Under this model, which became the logic of U.S. foreign assistance programs during much of the Cold War (1945–90), societies like Argentina, Brazil, and Chile should embark on projects to become more like the United States. Understandably, this model appealed to mid-century U.S. intellectuals and policymakers. In Latin America, modernization theory and its colonialist implications, held less sway.

The most powerful diagnoses of underdevelopment and its remedies came from Latin America itself, especially the social scientists associated with the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA), headquartered in Santiago, Chile, and directed between 1950 and 1963 by Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch. Prebisch’s approach, structuralism, interpreted the world as divided between a core (countries which were capital rich and industrialized), and a periphery (poor countries which relied on exports of raw materials, and were politically and economically vulnerable to the influence of core nations). For Prebisch, Latin American countries could not industrialize just by following liberal free-market rules. Instead, industrialization needed a push by the state through a process called import-substitution industrialization (ISI). This could be achieved through tariff barriers to keep imports out, as well as state financing or even ownership of industry. Prebisch’s ideas were a located between liberal thought and more radical developmentalist thinking. For instance, he believed ISI had to be balanced with private ownership, free trade, and limited public spending.

Prebisch’s approach became a springboard for a new interpretation of development and underdevelopment called dependency theory, pioneered by later generations of social scientists affiliated with ECLA. Dependency theorists offered a new diagnosis of the conditions that made that role necessary: industrialized countries in the northern hemisphere prevented the industrialization of countries in the southern hemisphere. Dependency theory was largely the opposite of modernization theory: it saw the terms of the relationship of countries like Argentina to countries like the United States as a perverse engine that inhibited development and reinforced inequality in Latin America. It was also pessimistic that development could be achieved under capitalism.

Dependency theorists drew from Marxism as well as from Prebisch’s structuralism. They believed the relationship between core and periphery trapped Latin America in poverty and underdevelopment. Specifically, trade between the United States and countries like Argentina, Brazil, or Chile was governed by “unequal exchange” between the low value of agricultural and mineral exports relative to the high value of manufactured imports. This unequal exchange was dynamic: over time, the value of agricultural goods continued to decrease relative to the value of industrial goods.1 In other words, Chile would have to export many, many grapes in order for a few Chileans to afford a car imported from the United States. In turn, exporting cars meant that many more people in the United States could afford Chilean grapes. Dependency theory explained that this growing differential trapped these countries in underdevelopment.

The solution to this problem, according to structuralists and dependency theorists was to replace the free-market doctrine of promoting the export of commodities for which they had a comparative market advantage (like coffee or copper) with policies such as ISI, fostering the creation of domestic industry. Dependency theorists went further, stressing social and economic reforms to combat poverty, such as land redistribution. These perspectives were widely shared: Prebisch was Argentine, Chile was the host of ECLA, and many influential dependency theorists were Brazilian, including Celso Furtado, who would serve as minister of planning (1962–3) and Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who would be the first elected Brazilian president to serve his full term after the end of military rule (1994–2002), though by this point he had renounced the theories he pioneered. Not all Latin Americans were dependency theorists, and disputes about the path to development paved the road to dictatorship, as three examples show.

In Brazil, the debate over oil exploration exemplified divergent paths to development. Nationalists like populist Getúlio Vargas rallied around the slogan “the oil is ours!” and sought to create a state monopoly to control the new industry. Since oil was a strategic resource, it should not be owned by foreigners, nor should foreigners reap the profits from extracting and refining Brazilian oil for Brazilian consumers. Conservative opponents argued for foreign investment: it was foreign companies, not the state, which had the capital and the technology to develop the oil industry. The outcome was a compromise: a new state company, Petrobras, held a monopoly over extraction but shared refining and distribution with private (mostly foreign) companies. The debate over oil reflected the ongoing political struggle over the development.

In Argentina, populist Juan Perón nationalized industries and pushed ISI to a degree well beyond that advocated by structuralists and dependency theorists. Prebisch disagreed with Perón’s takeover of the Central Bank (which Prebisch had directed from 1935 until 1943) and resigned his faculty position at the University of Buenos Aires in 1947 when the university refused to remove his name from a list of supporters of Perón’s economic plans.2 Peronists and leftists in Argentina disdained Prebisch’s approach because of its emphasis on private ownership of industry, foreign investment, and economic stability.

Among these leaders, Salvador Allende took the most radical path to breaking economic dependency. His 1970 electoral program explained “Chile is a capitalist country, dependent on the imperialist nations and dominated by bourgeois groups who are structurally related to foreign capital and cannot resolve the country’s fundamental problems.”3 Allende’s approach went beyond the prescriptions of structuralists and dependency theorists like his friend Prebisch. He pursued socialization of the economy through nationalization of banks, utilities and the foreign-owned copper industry (which accounted for the 80% of Chile’s exports and was primarily held by U.S. Anaconda Mining), as well as accelerated redistribution of land. Politically, these economic changes would be matched by a process of empowering workers and communities to make local decisions. This would be a new historical course, liberating Chile from dependency on foreign capital and its domestic allies. Allende called it the Chilean Road to Socialism.

The Cold War in Latin America

The debate over development was intensified by the U.S. Cold War doctrine of containment, which sought to prevent the spread of communism beyond Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. The United States pressed Latin American countries to adhere to free-market policies, provide a supportive environment for U.S. business, and reject Marxism and Socialism. The United States counted on the support of traditionally wealthy and powerful social classes in Latin America whose fortunes were often tied to trade with the United States or to American business interests. The United States also cultivated Latin American armed forces by providing training, financing, and equipment. U.S influence was not just overwhelming, when necessary it was enforced with violence, either by supporting military coups or through occasional direct military intervention.

The United States and its allies within Latin America used a wide brush to paint populism, developmentalism, and nationalism red. Much of the Latin American political and economic spectrum – ranging from moderate developmentalists like Prebisch to populist nationalists like Juan Perón and Getúlio Vargas, to Socialists like Salvador Allende, and beyond them to the revolutionary Marxist left – faced U.S. antagonism. U.S. policymakers defended archaic social, economic and political orders that reflected legacies of exclusion and exploitation that were often inherited from the colonial era. This alliance resulted in the violent suppression of social movements and radicalization of those seeking social change.

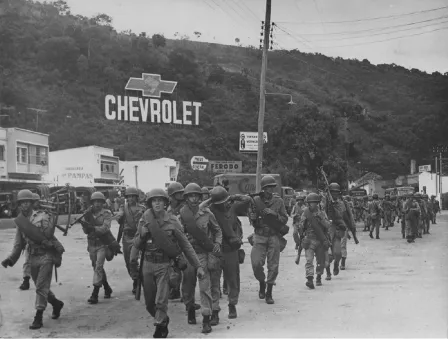

Figure 1.1 Soldiers marching beneath a Chevrolet advertisement during the Brazilian military coup, 1964.

Source: © Arquivo Nacional, Brazil.

U.S. Cold War policy in Latin America varied in its nature and degree. In the Caribbean and Central America, the United States often employed direct intervention, such as orchestrating the military coup that deposed the reformist president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz (1954), and invasions of the Dominican Republic (1965), Grenada (1983), and Panama (1989), as well as a failed invasion of Cuba (1961). South American countries were not in the direct shadow of the United States. Since the United States could not impose its objectives as directly, it worked through allies among the armed forces as well as domestic and international business groups. U.S. companies became proxies for U.S. foreign policy: Ford and General Motors funded secret police and death squads in Argentina and Brazil. International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) supported groups seeking to overthrow Chile’s Allende.

The 1959 Cuban Revolution was a watershed. Cuba’s economy was closely tied to the United States and its political system was shaped by repeated U.S. intervention. Fidel Castro’s movement had a clear goal among its initial objectives: attaining autonomy from the United States Castro adhered to Marxism only gradually as his regime distanced itself from the U.S and carried out social and economic reforms. Since the Cuban economy was vulnerable to sanctions imposed by the U.S. government, Castro pursued a relationship with the Soviet Union that was cemented by the failed U.S. attempt to land a military force of Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, followed 18 months later by the Cuban missile crisis. Yet Castro bristled at trading one form of dependency for another. Often in defiance of the Soviet Union, Castro supported revolutionary movements in Latin America and Africa in order to create a block of liberated nations that could become politically and economically autonomous from both the United States and the Soviet Union.

For the left, and particularly among university students, the Cuban Revolution suggested that the transformation of a society to alleviate historic injustices could be done with heroic speed. Underdevelopment could be vanquished through more direct means than those advocated by developmentalists like Prebisch. The revolutionary regime nationalized industries and large farms, implemented reforms protecting the poor from landlords, created a socialist economy, eliminated malnutrition by rationing and equitably distributing food, eradicated illiteracy, and made education and healthcare free and universally accessible. These achievements were the envy of social reformers across Latin America. What was more, the Cuban Revolution seemed to show that insurgency could be a successful path to power, and that once in power, leftists could quickly and decisively transform a society.

For the right, the Cuban Revolution inspired fear and intensified its willingness (present long before 1959) to violate the constitutional order to preserve the social and economic order. For the United States, it seemed to validate the Containment Doctrine. For Latin American armed forces, the revolution expanded the meaning of national security to incorporate action within national borders and against their own citizens, and intensified the stakes of that struggle. Castro had executed the officers of the president he deposed, so Latin American military officers saw their struggle against insurgencies as a fight to the death: they would not surrender to revolutionary groups out of fear they would be dealt the same hand.

The trajectory of Che Guevara reflects the dynamics of revolution. An Argentine doctor, Guevara traveled to Guatemala with an interest in Arbenz’s reforms. He fled to Mexico after the U.S.-backed coup and met Fidel Castro. When Castro mounted his insurgency in Cuba, Guevara became the movement’s strategist. In revolutionary Cuba, Guevara implement his far-ranging ideals for creating a more just society by seeking to eliminate the profit motive as an economic engine out of the belief that profit engendered exploitation. As minister of industry, Guevara’s ideals proved ruinous. Guevara left to continue supporting movements for liberation, first in Zaire, then in Bolivia, where he was captured and killed by troops trained by the United States.

The methods of guerrilla war proposed by Guevara, and refined by French collaborator...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Viewpoints/Puntos de Vista

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Illustrations

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Dependency, Development, and Liberation: Latin America in the Cold War

- 2 Brazil: What Road to Development?

- 3 Argentina: Between Peronism and Military Rule

- 4 Chile: From Pluralistic Socialism to Authoritarian Free Market

- 5 Argentina: The Terrorist State

- 6 Brazil: The Long Road Back

- 7 Chile: A “Protected Democracy”?

- Conclusion

- Sources

- Index