![]()

SECTION 1

IMPORTANT CONTEXTS FOR RESEARCH ON CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT

JAMES H. MCMILLAN

Associate Editor

![]()

1

WHY WE NEED RESEARCH ON CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT

JAMES H. MCMILLAN

In 1973, I took a measurement class from Bob Ebel at Michigan State University. Bob was a respected measurement authority, educated at an assessment mecca, the University of Iowa, by none other than E. F. Lindquist. We used Ebel’s textbook Essentials of Educational Measurement (Ebel, 1972), which devoted 400 pages—out of 650 pages for the entire book—to what he said were principles of classroom testing. There were chapters on test reliability and validity, different types of tests, and test score statistics, all directed at what teachers do in the classroom. This suggests that interest in classroom assessment (CA), or perhaps more accurately, how teachers test students in the classroom, has been around for a long time. Looking back, though, the course I took mostly reflected the application of summative psychometric measurement principles to teaching. The classroom, and what teachers did in the classroom, were essentially only the setting in which the principles were applied. There was little regard for CA as integrated with teaching or as a separate field of study.

Fast-forward to today … First, I believe Bob Ebel would be pleased with what has happened to CA, because he was always concerned about student learning. But I think he would be surprised by how CA has matured into a field that is separating itself from traditional notions of psychometrically based measurement, the theories and principles he relied on to write his book. CA is becoming a substantial field of study—one that is increasing a knowledge base so that progress can be made in what Bob was most concerned about: enhancing student achievement. However, the research that is needed to provide a comprehensive foundation for CA is splintered. It has been reported here and there but has not found a home or permanent identity. It is given relatively little attention from the National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME), not withstanding efforts by Rick Stiggins, Jim Popham, Susan M. Brookhart, Lorrie Shepard, and a few others, dwarfed by the psychometrics of large-scale testing.

This handbook is meant to signal the beginning of CA as a separate and distinct field of study with an identifiable research base, a field that integrates three areas: what we know about measurement, student learning and motivation, and instruction. While combining these three areas in a meaningful way is not new (see Cizek, 1997; Guskey, 2003; Pellegrino, Chudowsky, & Glaser, 2001; and Shepard, 2000, 2006), the present volume aims to provide a basis for the research that is needed to establish enduring principles of CA that will enhance as well as document student learning. It is about the need to establish a more formal body of research that can provide a foundation for growing our knowledge about how CA is undertaken and how it can be effective in enhancing student learning and motivation. Our collective assertion is that CA is the most powerful type of measurement in education that influences student learning.

CA is a broad and evolving conceptualization of a process that teachers and students use in collecting, evaluating, and using evidence of student learning for a variety of purposes, including diagnosing student strengths and weaknesses, monitoring student progress toward meeting desired levels of proficiency, assigning grades, and providing feedback to parents. That is, CA is a tool teachers use to gather relevant data and information to make well-supported inferences about what students know, understand, and can do (Shavelson & Towne, 2002), as well as a vehicle through which student learning and motivation are enhanced. CA enhances teachers’ judgments about student competence by providing reasoned evidence in a variety of forms gathered at different times. It is distinguished from large-scale or standardized, whether standards-based, personality, aptitude, or benchmark- or interim-type tests. It is locally controlled and consists of a broad range of measures, including both structured techniques such as tests, papers, student self-assessment, reports, and portfolios, as well as informal ways of collecting evidence, including anecdotal observation and spontaneous questioning of students. It is more than mere measurement or quantification of student performance. CA connects learning targets to effective assessment practices teachers use in their classrooms to monitor and improve student learning. When CA is integrated with and related to learning, motivation, and curriculum it both educates students and improves their learning.

A CHANGING CONTEXT FOR RESEARCH ON CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT

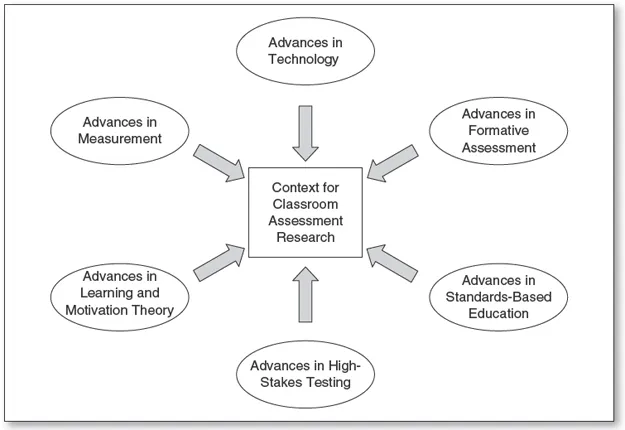

In this section, I want to outline important factors that frame issues and considerations in research on CA. I argue that changes in several areas set the current context, which influences what research questions are appropriate, what methodologies are needed, and what advances can be expected. As depicted in Figure 1.1, there is a dynamic convergence of these contextual factors that influence CA research. The good news is that the emphasis is on how to generate knowledge about effective assessment for learning (AFL) and assessment as learning. As appropriate, I’ll also indicate how subsequent chapters in this handbook address many of these factors.

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, there are six major factors that have a significant influence on the current context in which CA research is conducted. For each of these six, there are important advances in knowledge and practice, and together they impact the nature of the research that needs to be designed, completed, and disseminated. Each is considered in more detail.

Advances in Measurement

Throughout most of the 20th century, the research on assessment in education focused on the role of standardized testing (Shepard, 2006; Stiggins & Conklin, 1992). It was clear that the professional educational measurement community was concerned with the role of standardized testing, both from a large-scale assessment perspective as well as with how teachers used test data for instruction in their own classrooms. Until late in the century, there was simply little emphasis on CA, and the small number of studies that researched CA was made up of largely descriptive studies, depicting what teachers did with testing and grading. For example, an entire issue of the Journal of Educational Measurement, purportedly focused on “the state of the art integrating testing and instruction,” excluded teacher-made tests (Burstein, 1983). The first three editions of Educational Measurement (Lindquist, 1951; Linn, 1989; Thorndike, 1971), which were designed with the goal of presenting important, state-of-the-art measurement topics with chapters written by prominent measurement experts, did not include a chapter on CA (that changed with Lorrie Shepard’s chapter in the 2006 edition [Shepard, 2006]. Similarly, the first three editions of the Handbook of Research on Teaching (Gage, 1963; Travers, 1973; Wittrock, 1986) had little to say about CA or, for that matter, about testing more broadly (Shepard provided a chapter on classroom assessment in the fourth edition [Shepard, 2001]). The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association [AERA], American Psychological Association [APA], and the National Council on Measurement in Education [NCME], 1999) does not explicitly address CA, nor are the standards written for practitioners. While the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing contains a separate chapter on educational testing and assessment, it focuses on “routine school, district, state, or other system-wide testing programs, testing for selection in higher education, and individualized special needs testing” (p. 137). Clearly, the last century established what could be described as a psycho-metric/measurement paradigm, a powerful context in which attention to assessment focused on the psychometric principles of large-scale testing and corresponding formal, technical, and statistical topics for all educators, including teachers.

| Figure 1.1 | Factors Influencing Classroom Assessment Research |

The cultural and political backdrop of earlier research examined issues pertaining to “assessment of learning” (evidenced by summative test scores; for more information on summative assessments, see Chapter 14 by Connie M. Moss). Inadequacies of assessment training in teacher education were reported many decades ago (Goslin, 1967; Mayo, 1964; Noll, 1955; Roeder, 1972). Subsequent research echoed the shortcomings of teacher education in the assessment area, calling for improved preparation (Brookhart, 2001; Campbell & Evans, 2000; Green & Mantz, 2002; Hills, 1977; Schafer & Lissitz, 1987) and for preparation to be relevant to the assessment realities of the classroom (Stiggins, 1991; Stiggins & Conklin, 1992; Wise, Lukin, & Roos, 1991). Others researched and suggested needed teacher assessment competencies (Plake & Impara, 1997; Schafer, 1993). A generalized finding was that, by and large, teachers lack expertise in the construction and interpretation of assessments they design and use to evaluate student learning (Marso & Pigge, 1993; Plake & Impara, 1997; Plake, Impara, & Fager, 1993), though this referred primarily to constructing, administering, and interpreting summative assessments. When AFL is emphasized, different teacher competencies are needed, including the need for teachers to clearly understand the cognitive elements that are essential to student learning, such as being able to identify errors in cognitive processing that prevent students from advancing along a learning progression (Heritage, 2008).

Similarly, research investigating assessment as learning has documented the benefits of student involvement throughout the learning process—in particular, how peer and self-assessment enhances metacognition and ownership of learning as a result of active involvement in evaluating ones own work (Dann, 2002; Shepard, 2000; see also Chapters 21 and 22 of this volume).

A systemic effect on the United States’ educational system was fueled by A Nation at Risk (National Committee on Excellence in Education, 1983), which suggested the need for substantial improvement in teacher preparation programs. Following this report, many states updated or initiated state-required proficiency exams for beginning teachers. Concurring with the need for teachers to be able to accurately assess student learning, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the NCME, and the National Education Association (NEA) developed Standards for Teacher Competence in Educational Assessment of Students (American Federation of Teachers (AFT), NCME, and National Education Association [NEA], 1990), which summarized critical assessment knowledge and skills and provided a guide for research, teacher preparation, and professional development. These standards have been updated by Brookhart (2011) to incorporate learning and teaching as important components of what teachers need to know to be effective assessors in the classroom.

Though the context of research for CA has shifted away from specific large-scale testing principles, the fundamental ideas of validity, reliability, and fairness are still very much a part of understanding what occurs in the classroom and research on CA. From the perspective of researchers, traditional ideas of validity, reliability, and fairness are used to assure adequate instrumentation and credible data gathering. Our emphasis here is on the validity, reliability, and fairness of CAs. In Chapter 6, Sarah M. Bonner suggests new viewpoints about the validity of CAs. She presents five principles based on new interpretations from traditional conceptualizations of validity. These include (1) alignment with instruction, (2) minimal bias, (3) an emphasis on substantive processes of learning, (4) the effects of assessment-based interpretations, and (5) the importance of validity evidence from multiple stakeholders. These principles extend the idea of validity—evidence of the appropriateness of interpretations, conclusions, and use—to be more relevant to classroom settings. This extends earlier work by Brookhart (2003) and Moss (2003) on the need to reconceptualize validity to be more useful for CA. In addition, Margaret Heritage, in Chapter 11, focuses on validity in gathering evidence for formative assessment.

New thinking is also presented in this volume on reliability and fairness, which also have been conceptualized mainly from technical requirements of large-scale assessment. Jay Parkes, in Chapter 7, posited a reconceptualization of reliability, one that blends measurement and instruction, considers teacher decision making and a subjective inferential process of data gathering, and includes social dynamics in the classroom. He proposes a new conceptual framework for the development of CA reliability. In Chapter 8, Robin D. Tierney argues that fairness for CA, while inconsistently defined in the literature, is best conceptualized as a series of practices, including transparency of assessment learning expectations and criteria for evaluating work, opportunity to learn and demonstrate learning, consistency and equitability for all students, critical reflection, and the creation and maintenance of a constructive learning environment in which assessment is used to improve learning.

This is not to suggest that there were not some attempts during the last part of the 20th century to study CA. Shepard (2006) summarized several of these efforts, which gathered momentum in the 1980s. These studies highlighted the need to understand teachers’ everyday decision making concerning both instruction and assessment. Two landmark publications (Crooks, 1988; Stiggins & Conklin, 1992) summarized data to describe the complex landscape of CA and set the stage for a surge of interest in understanding how teachers assess and what the nature of teacher preparation should look like to ensure that teachers have the knowledge and skills to effectively develop, implement, and use assessments they administer in their classrooms. During the 1990s, CA established an independent identity with the publication of textbooks (e.g., Airasian, 1991; McMillan, 1997; Popham, 1995; Stiggins, 1994; Wiggins, 1998), the Handbook of Classroom Assessment: Learning, Adjustment, and Achievement (Phye, 1997), and forming of the Classroom Assessment Special Interest Group in AERA. Significantly, in Great Britain, the Assessment Reform Group, which was started in 1989 as a task group of the British Educational Research Association, initiated study...