eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Marketing Research

Uses, Misuses, and Future Advances

This is a test

- 720 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Handbook of Marketing Research: Uses, Misuses, and Future Advances comprehensively explores the approaches for delivering market insights for fact-based decision making in a market-oriented firm. Divided into four parts, the Handbook addresses (1) the different nuances of delivering insights; (2) quantitative, qualitative, and online data gathering techniques; (3) basic and advanced data analysis methods; and (4) the substantial marketing issues that clients are interested in resolving through marketing research.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Marketing Research by Rajiv Grover, Marco Vriens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing Research. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FOUNDATIONAL DESIGN

1

TRUSTED ADVISER

How It Helps Lay the Foundations for Insights

As alluded to in the Introduction of the book, the trusted adviser status enables the market researcher to delineate the right problem definition, which, in turn, ensures that insights will be generated. In this chapter, we develop two processes for arriving at the right problem definition under the trusted adviser model of engagement. The first process applies to a class of problems that we term as decision-making problems. These normally stem from or surface with a symptom. The second process pertains to the market-learning class of problems that begin with a fuzzy, broad-based need for information. Since for both these processes, it is essential that the market researcher serve in the capacity of trusted adviser, we first establish the need for trust in the marketing research context, build a model of trust, and develop the attributes of a trusted adviser.

THE NEED FOR TRUST IN THE MARKETING RESEARCH CONTEXT

Research has shown that trust between two parties results in better quality of decisions and, therefore, in the performance of the dyadic unit. Trust engenders better usage of marketing research results and mutual satisfaction with the relationship between the researcher and the client. When trust exists between two parties, the following factors facilitate the resulting positive outcomes: (a) open communication, (b) lesser blame attribution and conflict, (c) acceptance to influence and control by the other, and (d) exhibition of positive behaviors beyond the call of duty (Zand, 1972).

Although it may be clear why trust is important between a client and an outside supplier, its significance in an in-house context might not be evident. Even when internal researchers conduct the research, their clients in the same company are exposed to risks. And when there is risk, there is a need for trust (see, e.g., Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). In the context of marketing research, there are two types of risks that clients face, which might be termed as information usage risk and personal exposure risk.

Information usage risk is that which results from the use of information provided by the market researcher, and it exists because information is inherently never fully accurate or complete. In the context of market research, inaccuracies of information stem from research design as well as execution of the design. Every research design has some potential for bias, and further errors occur during execution of the research. For example, the design of a mail survey may be tainted by any one or more of the standard sources of bias: leading questions, questions that result in alternative interpretation, or questions that test the limits of the recallability of respondents. Even if these design biases are addressed, biases in execution, such as in sampling and/or that resulting from nonresponse, might still prevail. In other words, the results of a particular market research project might be idiosyncratic in the sense that the same problem researched with another audience or method might yield different results. Besides inaccuracy, incompleteness of information generated by market research is quite inevitable. For making a decision, several aspects of the problem might need to be investigated, but not all aspects might be obvious and/or researchable due to the potential practical constraints. Thus, the market researcher might not be able to take those aspects into consideration, ultimately leading to provision to the client of information that is incomplete.

The second type of risk, personal exposure risk, is the risk the client faces of being upstaged by the researcher, and it exists because the market researcher has an edge over the client in having more information about the project than the client. The market researcher can potentially leverage the imbalance of information to gain and demonstrate undue advantage over the client in situations where parties are present to discuss the results with others in the organization. This threat is one of the factors that prevents clients from offering market researchers “a seat at the table.”

The above risks dictate the need for two types of trust that the client must find in the researcher: professional and personal. The next section discusses these two types of trust.

A Model of Trust

The construct of trust is among the most researched concepts as it has a useful role in many disciplines (e.g., organization behavior, sociology, psychology). Correspondingly, there are numerous definitions of the concept (see, e.g., Bigley & Pearce, 1998; Mayer et al., 1995).1 From our perspective, we adopt the following definition of trust, “the willingness of a client (trustor) to be vulnerable to the actions of a market researcher (trustee) based on the expectation that the researcher will perform a particular action important to the client, irrespective of the client’s ability to monitor or control the researcher” (Mayer, et al., 1995). This definition weighs in on “willingness,” whereas other conceptualizations in academic research put forth the concept as a “belief,” a belief about the exchange partner’s trustworthiness (e.g., honesty, integrity, capability), or as an “expectancy,” an expectancy that a person can be relied on. From a practical point of view, these definitions have the same implications.

Literature has also identified many bases of trust. The term basis denotes the origin or source of trust in a trustor. Two of these that have been considered as umbrella sources are cognitive and affective bases (Jeffries & Reed, 2000).2 A cognitive basis of trust exists when trustors use rational reasons to trust the trustees. Such rational reasons relate to objective evaluations of the trustee’s expertise, dependability, or work quality. Conversely, an affective or emotional basis of trust stems from a “gut” feeling of the trustor, who relies on traits such as likeability or similarity to judge the trustee.

The two types of risks—information usage and personal exposure—and the two bases of trust—cognitive and affective—translate well into the two types of trust we propose. The first of these, “professional” trust, refers to a client’s trust in the market researcher’s capability to provide as accurate and complete as possible information that is required for decision making. It stands to reason that such trust would be strongly based on the cognitive component. The second type of trust, “personal” trust, pertains to the trust a client has in the market researcher regarding the latter supporting and promoting the client or the client’s cause in various forums. Research on homophily in the sociology area points to the affective basis as the source of personal trust.

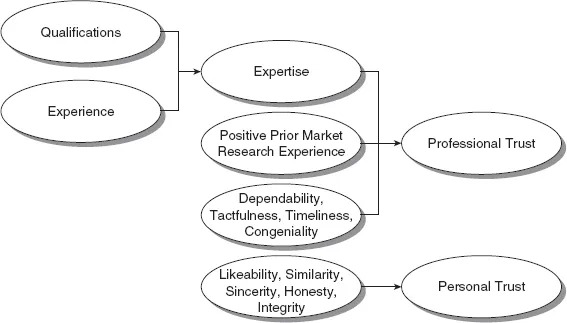

Figure 1.1 Factors Forming Professional and Personal Trust

Figure 1.1 shows the factors that influence professional and personal trust. Professional trust that a client has in a market researcher results from the expertise of the market researcher and the client’s prior direct or indirect experiences with the market researcher. The market researcher’s expertise is judged by the client on the basis of the former’s qualifications and experience. The other major component that leads to professional trust in the market researcher is the professionalism demonstrated by the market researcher. The indicators of professionalism include dependability, timeliness, congeniality, and tactfulness (Moorman, Deshpandé, & Zaltman, 1993). The figure shows that formative indicators of personal trust in a market researcher are qualities such as likeability, similarity, sincerity, honesty, and integrity of the market researcher.3

Constituent Attributes of a Trusted Adviser

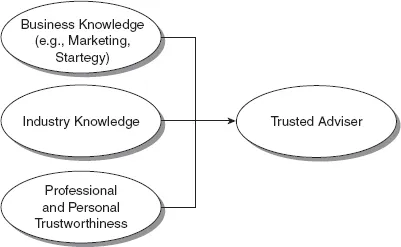

From the above discussion, it is clear that professional and personal trustworthiness are two key attributes a market researcher needs to demonstrate to be able to serve and be accepted as a trusted adviser. Among all the formative characteristics of the two types of trust shown in Figure 1.1, in-depth marketing research knowledge is perhaps the most important. That knowledge by itself, however, is not enough to transform the market researcher into a trusted adviser. Beyond marketing research knowledge, a trusted adviser needs to also be equipped with business knowledge. By business knowledge, we refer to knowledge of subject areas such as new product development, branding strategies, consumer behavior, organization buying behavior, pricing, distribution channels, promotions, marketing strategy, and so forth. The implication is that for researching and acquiring insights into an advertising issue, for example, a researcher must have a good understanding of the advertising discipline. Industry knowledge subsumes knowledge about the organization’s products and strategies and about the products and strategies of competitors. Figure 1.2 summarizes the key attributes that help a market researcher develop into a trusted adviser.

Figure 1.2 Attributes of a Trusted Adviser

Having stated the case for the client’s need to be able to trust the market researcher, we next propose that the market researcher also needs to be able to trust the client—that is, trust the client to provide the right information to enable the formulation of the right problem definition. If the client does not reveal all the relevant information, the market researcher will be unable to provide a meaningful solution.

Figure 1.3 graphs the total amount of mutual trust between a client and a market researcher. On the far left-hand side, the client uses the market researcher only for data collection. The market researcher, perceived to have weak industry and business knowledge, is told what to collect, thus making the market researcher an order taker. At the extreme right-hand side, the client has a weak base of marketing research knowledge and is unable to gauge the contribution of marketing research in the yet unspecified needs for information. The researcher is not able to trust the client to articulate the issues completely. In such a situation, the marketing researcher will end up shooting in the dark. In the middle of the graph, both the market researcher and the client have the requisite amounts of knowledge of the industry, the business discipline, and marketing research—with the researcher knowing more about the research function and the client more about his or her own function (see Madhavan & Grover, 1998). The potential of the mutual amount of trust is maximum in this situation. The market researcher can behave and serve as a trusted adviser, and the client also accepts him or her in this role.

When the market researcher is a trusted adviser, the client articulates the symptoms of the problem to the market researcher, who then interacts with the client to determine the problem and the research approach. In such a role, the market researcher evaluates the diagnosis, designs and executes the methodologies for gathering complete and accurate data, and interprets the implications of the findings for the client. This dynamic scenario is analogous to the patient-physician interaction and relationship. The physician diagnoses the problem from the symptoms articulated by the patient and then prescribes a treatment regimen. Just as a physician would resist and refuse a request for a particular drug that is unwarranted, we argue that the market researcher should resist and refuse to take orders from the client regarding the type of data or methods of data collection. Just as a physician would be prescribing in the dark if the patient does not disclose, whether intentionally or unintentionally, all the symptoms and case history, we argue that a researcher would be shooting in the dark if the client is not able to provide or is not forthcoming with all the necessary information. Finally, just as a physician is proactive in advising checkups to the patient, we recommend that as a trusted adviser, a market researcher should be proactive in advising clients on when and what to research next. In short, a market researcher should strive to develop a relationship with the client similar to the one that a physician has with a patient.

Figure 1.3 Total Mutual Trust and Strengths of the Client and the Researcher

From the above analogy, it also follows that many times, the patient (client) might not be aware of what information would be relevant to the physician (researcher), and hence it behooves and falls upon the physician (researcher) to ask the right questions when interacting with the patient (client). In other words, client-researcher interaction becomes key in determining whether and how the root problem is identified. The processes for such interaction between client and researcher to arrive at the stage of problem definition are developed next.

PROCESSES FOR DEFINING MARKET RESEARCH PROBLEMS

Marketing problems that can be addressed by marketing research can be broadly classified into two categories: decision-making problems and market-learning problems. Decision-making problems are those that, when solved, help clients make a decision. Market-learning problems, on the other hand, are those that, when addressed, shed light on the company’s and the competitors’ products, existing and potential customers, environment, and so forth. The answers to such problems are not necessarily used for making imminent decisions. There is a distinct and separate process for arriving at the problem definition for each of these two types of problem. Both the processes require the trusted adviser status of the marketing researcher.

The Process for Defining Decision-Making Problems

A characteristic of the decision-making class of problems is that it is the symptom that first emerges. The symptom could be a decline in sales or market share, a decline in customer or distributo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Changing World of Marketing Research

- Acknowledgments

- PART I: Foundational Design

- PART II: Data Collection

- PART III: Analysis and Modeling

- PART IV: Conceptual Applications

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors