eBook - ePub

Ten Best Teaching Practices

How Brain Research and Learning Styles Define Teaching Competencies

This is a test

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ten Best Teaching Practices

How Brain Research and Learning Styles Define Teaching Competencies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Engage, motivate, and inspire students with today’s best practices

In this third edition of her classic methods text, Donna Walker Tileston engages readers from the beginning with real-life classroom examples, proven techniques for reaching every learner, and up-to-date strategies, all outlined in her reader-friendly style. She incorporates the latest research on brain-compatible pedagogy and learning styles throughout the updated chapters on today’s most critical topics, including:

- Using formative assessment for best results

- Integrating technology to connect students’ school and home lives

- Differentiating instruction to inspire all students

- Creating a collaborative learning environment

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ten Best Teaching Practices by Donna E. Walker Tileston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Creating an Environment That Facilitates Learning

The difference between an expectation and a standard is that the standard is the bar, and the expectation is our belief about whether students will ever reach the bar.

—Robyn R. Jackson

In the first edition of this book, I wrote the following lines about creating a classroom environment that is conducive to learning. I repeat them here because the importance of this aspect of learning remains paramount to the craft of teaching:

An enriched and supportive environment is so important that none of the other techniques discussed will be really effective unless the issues of enrichment and support are addressed first. In a world full of broken relationships, broken promises, and broken hearts, a strong supportive relationship is important to students. While we cannot control the students’ environments outside the classroom, we have tremendous control over their environment for seven hours each day. We have the power to create positive or negative images about education, to develop an enriched environment, and to become the catalysts for active learning. We now know that how we feel about education has great impact on how the brain reacts to it. Emotion and cognitive learning are not separate entities; they work in tandem with one another. (Tileston, 2005, p. 1)

Ask teachers what is keeping them from being the kind of teacher they dreamed of being and you will probably get an answer that involves the motivation level or lack thereof demonstrated by their students. Through current brain research, we know so much more now about what causes us to be motivated to learn and to complete tasks at a high level. In his groundbreaking book Drive, Daniel Pink (2009) surprises us with what current brain research says about what really motivates our students and us. In the last century we relied on the carrot-and-stick approach to motivating our students. We offered tangible rewards for finished work and behavior such as stickers, free time, prizes, and even money. Pink says that in this day and time what truly motivates us clusters around three things: (1) autonomy, (2) mastery, and (3) purpose.

THE NEED FOR AUTONOMY IN THE CLASSROOM

We seem to be hardwired to be active, engaged, and curious. Pink (2009) calls this our default switch, and he adds that when we reach a point in our lives—whether it is in middle school or middle age—that we are not curious and actively engaged in learning, it is because something has turned the switch to the “off” position. Watch a two-year-old at play if you have any doubts about these phenomena of natural curiosity. We help build autonomy or self-direction in our students through task, time, technique, and team.

Task: When possible, give students choices in how they demonstrate understanding, the independent projects that they work on, and in how they tackle procedural tasks. Provide the parameters and the scaffolding needed and then stand back and let students work on the tasks. In the last century we were so fixed on a model from industry that compartmentalized and standardized everything that even elementary-classroom art projects became cookie cutter works. This century is about creativity, and it is time to throw away the cookie cutters.

Time: Time is the brutal enemy of understanding in the classroom. We live by a set of standards that must be taught in a given amount of time—and too often it is time that rules how and what we teach, rather than student success and understanding. What if we got rid of this “tail wagging the dog” idea and began to believe and implement a system that allowed students more time if they needed it or wanted it to create a better product? What if we put the emphasis on the quality of the learning rather than on just covering the subject? What if we looked at progress over time rather than time over progress?

Technique: Autonomy over technique refers to providing choices to students when they do group or individual projects and when they demonstrate understanding. To the extent possible, allow students to show that they understand through a variety of ways such as written or verbal projects, demonstrations, models, or using a kinesthetic or other creative approach of their own. In my workshops I often use the following problem to demonstrate this technique: There are 100 people in a room. If everyone in the room shakes hands with everyone else, how many handshakes is this? For the verbal learners, there is a formula; for the visual learners, they can draw or use graphics to show the answer; and for the kinesthetic learners, they can demonstrate the answer.

Team: Autonomy over teams occurs when I allow students to create social networks of their own choosing to study together, complete projects together, and to collaborate. As technology becomes available to each student, those networks can go beyond the classroom. For example, a small group is working on an independent project in the form of a book report using technology. The group might want to add to their team a teacher or peer who has used this method successfully online or a consultant from one of the universities where this technique has been developed. There are places right now where students are doing this—where learning is not limited by the classroom teacher or by the bricks and mortar of a school building—and it adds great depth to the project. Jensen (1997) says that the best learning state for students is one in which there is mild stress—pushing the envelope slightly. In this state, students feel a nudge, but they have the knowledge base to be successful. In other words, when we push the envelope we need to be sure that our students have the foundation and the tools to be successful otherwise it becomes a high-stress situation in which none of us do our best work. Pink (2009) sums up autonomy with an important statement to those of us who value accountability:

Motivation 2.0 assumed that if people had freedom, they would shirk—and that autonomy was a way to bypass accountability. Motivation 3.0 begins with a different assumption. It presumes that people want to be accountable—and that making sure they have control over their task, their time, their technique, and their team is a pathway to that destination. (p. 107)

STUDENTS’ STATES OF MIND: MAKING LEARNING POSITIVE

Have you ever been so involved in a project that you literally lost track of time? You were completely engaged and were seeking mastery. Psychologist Csikszentmihalyi, as discussed by Pink (2009, p. 114), was curious as to what was going on in the brains of people while they were totally engaged in what they were doing. He found that people who are engaged, whether it is in learning or a project, are in a state of flow. It is the state of flow of the brain that causes us to pay attention, finish work at a high level, or sleep through class.

Our brains are constantly changing their emotional states (flow) based on both internal and external stimuli. Jensen (2003) explains these states as patterns in the brain that affect our behaviors. These patterns shift constantly as new stimuli change them. For example, a student may be listening to the teacher when a fight erupts in the hallway. Suddenly, her state has changed from attentive learner to one characterized by very different emotions such as excitement, disgust, anger, or sadness. The kinds of states that students bring to the classroom depend, in part, on the states that are dominant or most often used by them outside the classroom. We all have attractor states and repeller states.

Signature states or attractor states are the states that we enter most often. These neural networks have been strengthened over time through the emotions and sensations attached to that particular state. Jensen (2003) explains,

Some people laugh a lot because that’s their primary attractor state. Others are angry a lot—that’s their strongest attractor state. That state becomes their allostatic (adjusted stress load) state, instead of the healthier homeostatic state. The result is that they will often pick fights with others just to feel “like themselves” by reentering that familiar state. (p. 9)

States make up our personalities and can usually be predicted based on past experience. By the same token, our states in regard to learning are created by the experiences that we have most often in the classroom. If I experience failure, ridicule, embarrassment, or even fear in the classroom most often, then my state in that classroom will be based on avoiding those things. Repeller states are those states that we avoid, states that we experience only for short periods or in extremes. A student might experience failure in math and success in all other subjects; that experience will lead to a state for learning in all other classes except math. Jensen (2003) adds,

Our systems naturally repel these states when we move towards them. We tend to avoid them because the complex interplay of our intent (frontal lobes) and the myriad of our other subsystems (emotions, hunger, high-low energy cycles, heart rate, etc.) indicate that we’ll find no good maintaining in those states. (p.10)

Students enter our classrooms with a great deal going on in the brain that has nothing to do with the learning at hand. They may have had an argument at home before school or a negative experience in the hallway. They may be excited about an upcoming event or a new boyfriend or girlfriend. As teachers, we have a great deal of competition for our students’ attention. Learning is the “process by which our system memorizes these neuronal assemblies (our states) until they become attractor states” (Jensen, 2003, p. 10). What if students do not have attractor states about learning but have, over time, created a pattern for repelling the learning? We can guide them to a state in which learning is an attractor state. By using what we know about the brain and what attracts the brain to learning, we can, over time, reverse the state of mind of our students.

In order to bring students to mastery, we need to understand how to bring them to engagement in the learning. True mastery is a process of constantly moving past my “personal best.” What was my personal best in second-grade mathematics will not be good enough in third-grade mathematics. I am constantly trying to achieve greater heights. It is no surprise that during the winter Olympics, we constantly heard the words, “He has a new personal best with that score.” If I want students in my classroom to achieve mastery, I must help them to create personal goals for the learning, and I need to revisit those goals often to help my students see their progress. Most students have not been directly taught how to follow through when there are constraints to meeting their goals. Thus, they often throw up their hands and simply give up at the first sign of trouble. We can help our students to achieve mastery by teaching them positive self-talk; show them what you do when you cannot get a problem solved or how you determine the meaning of a new word in a sentence. In a study on why some cadets in military academies drop out and some stay regardless of circumstances (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007), researchers found that those who stayed with the program in spite of grueling and tough training were those who had a “grit,” the ability to effectively monitor and regroup when they were having difficulty with meeting long-term goals.

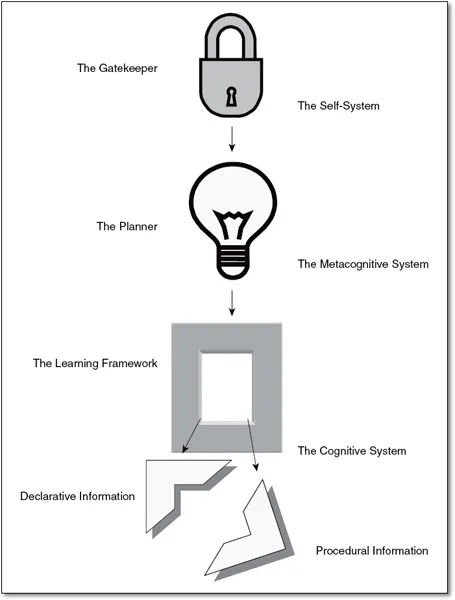

Most of us were taught to begin our teaching with the cognitive center of the brain. It is no wonder that teachers all over the country lament the fact that students are not motivated to learn. We know from researchers such as Marzano and Kendall (2008) that motivation to learn is controlled by the self-system of the brain, not the cognitive system. Let me say that again: all learning begins in the self-system of the brain. It is this system that decides whether the student will pay attention and engage in the learning; it is the learning state that most of us seek in our classrooms. Marzano (2001a) puts it this way:

The self-system consists of an interrelated system of attitudes, beliefs, and emotions. It is the interaction of these attitudes, beliefs, and emotions that determines both motivation and attention. Specifically, the self-system determines whether an individual will engage in or disengage in a given task; it also determines how much energy the individual will bring to the given task. (p.50)

Once the decision has been made to pay attention or begin a task, the metacognitive system of the brain takes over and makes a plan for carrying out the work. Only then is the cognitive system employed. Figure 1.1 is a graphic representation of this process.

Figure 1.1 The Systems of Thinking

As teachers, we need to be cognizant of the fact that the decision whether or not to engage in the learning is going to take place with or without us. We can influence that decision by the way we approach the teaching and learning process. We also can influence the learning state of our students through what we say and do. Jensen (2003, p. 11) says that we should target the state that we want for our students depending on the learning activity. He lists the states based on the amount of energy they require from highest need for energy to lowest need:

- Hyper, overactive

- Physically active, learning

- Writing or talking

- Focused thinking

- Alert concentration

- Scattered thinking

- Visualizing

- Relaxed focus

- Daydreaming

- Drowsy, drifting

The following three criteria are critical to the decision by the brain to pay attention to the learning (see Tileston, 2004a).

1. The Personal Importance of the Learning to the Student

No one will argue that learning is important. However, for learning to be addressed by the brain, it must be perceived as important to the individual. The first criterion is that the student must believe the learning satisfies a personal need or goal. Marzano (2001a) explains it this way: “What an individual considers to be important is probably a function of the extent to which it meets one of two conditions: it is perceived as instrumental in satisfying a basic need, or it is perceived as instrumental in the attainment of a personal goal.” Jensen (2010) reinforces the importance of goal setting as a way to emphasize the personal importance of the new learning to students. Jensen suggests,

Encourage students to set daily, weekly, and long-term goals. Check in with them on a regular basis, provide feedback, and validate their progress. For example, ask students to share their goals with classmates by posting them as timelines or charts. Public recognition is a great motivator and strategy for reinforcing progress. Once distressed learners set a goal, do everything in your power to help them succeed. (p. 68)

How many of us have heard students say, “When are we ever going to use this?” Students today are in information overload; if they only need to know it for the test on Friday, then they will memorize it long enough to put it on the test and then promptly forget it. If it has real-world meaning to them personally, it is more likely to be placed into long-term memory. Begin units of study by helping students see the importance of the learning to them personally. In his book, The Art and Science of Teaching: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Instruction (2007), Marzano cites a meta-analysis by Lipsey and Wilson (1993) in which 204 studies are synthesized to determine the effect size of setting goals. An effect size provides us with data on the effect of using a particular instructional strategy as opposed to classrooms where the strategy is not being used. We can ask the question, “If I use this strategy in my classroom, what will be the average effect on student learning? In this case the effect size was 0.55. This means that in the 204 studies they examined, the average score in classes where goal setting was effectively employed was 0.55 standard deviations greater than the average score in classes where goal setting was not employed” (Marzano, 2007, p. 11). Effect sizes can be interpreted as percentile gains as well. In this case, when goals and objectives were set for the learning,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- About the Author

- 1. Creating an Environment That Facilitates Learning

- 2. Differentiating for Different Learning Styles

- 3. Helping Students Make Connections From Prior Knowledge

- 4. Teaching for Long-Term Memory

- 5. Constructing Knowledge Through Higher-Level Thinking Processes

- 6. Fostering Collaborative Learning

- 7. Bridging the Gap Between All Learners

- 8. Evaluating Learning With Authentic Assessments

- 9. Encouraging In-Depth Understanding With Real-World Applications

- 10. Integrating Technology Seamlessly Into Instruction

- 11. Putting It All Together

- References

- Index