- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The articles are well-written and informative. . . . All the authors write with authority. . . . This is a sound and interesting . . . text that merits consideration as a library purchase, and has implications for researchers in the field of negotiation studies. --The Service Industries Journal "The essays . . . are of a consistently high standard. . . . The appendixes are well laid out with useful material for those engaged in teaching negotiatory skills, or developing programmes in this field. . . . The essays in this volume cover a wide range of topics. . . . The strength of the book, however, is that it provides a good blend of theory and practice in the art and science of negotiating in diverse settings. The book is well organized in a systematic manner, and deals in a logical way with the interaction processes in negotiating. . . . This book is highly recommended to practitioners who would find much by way of applicable theory developed from practice. It will be of interest to academics, and especially to those who use the case-study method of teaching in graduate courses." --Industrial Relations Journal "Negotiation is a valuable contribution for both negotiators and students of the process. Most of the authors are themselves both innovators in practice and scholars. The book is packed with so much wisdom . . . nuggets of insight and practical advice. Challenged with conveying such wisdom in a chapter, each author comes right to the point, usually in straightforward language, buttressed by vivid examples. It is a must read." --Richard E. Walton, Wallace Brett Donham Professor of Business Administration, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University "Negotiation: Strategies for Mutual Gain is a rich store of creative ideas and valuable advice by leading experts in the field of negotiation and conflict resolution." --Jeswald W. Salacuse, Dean, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University "Lavinia Hall has managed to pack into a single volume much of this country?s most provocative current work on the subject of what is known popularly as ?win-win? negotiations. The book should prove invaluable to those concerned with how we manage our differences--in the workplace, the courtroom, and at home. There is something in this volume for everyone." --Michael Lewis, President, ADR Associates, Washington, DC "Lavinia Hall has pulled together an excellent collection of readings. The articles represent important contributions by many of the leading thinkers in the fields of negotiation and dispute resolution. This is a very useful anthology." --Roy J. Lewicki, Professor of Management and Human Resources,

Information

PART II

Applying Mutual Gains to Organizations

Introduction

► Creating awareness of how different players perceive the real problem and helping to change locked-in, unproductive habits are the themes in this part about applying these problem-solving frameworks to organizations. The authors speak from their experiences in different settings and analyze the obstacles to applying their process frameworks in specific contexts.

Sander’s chapter on the range of dispute resolution techniques being used by the legal profession and courts is heartening. Saving time, energy, and money of the court system and individuals are goals, but they must not outweigh the overriding concern for fairness and the constitutional guarantees of due process.

Susskind applies his ideas to building consensus around how-to issues in public debate and demonstrates some successes that have been achieved using process skills. He views the processes as supplemental aids to existing public systems but to the extent that regulatory negotiation and other processes transform the way that public debate takes place, the change may be transformative rather than merely supplemental.

McKersie and Heckscher show how difficult unfreezing old habits can be, even in a climate in which those habits are self-defeating. They offer a number of suggestions and hopes for employment relations in the long run, while recognizing that many unionized organizations will need to make some painful adjustments if cooperative, mutual gains decision making is ever to become the predominant mode of collective bargaining. Although there are success stories, they are not the rule; their chapters point out why that is so and how some of the ideas and techniques presented here can help to change the existing paradigm.

Rowe offers many interesting insights around the issue of choice in organizational settings. Rather than arguing for one way of doing things, she urges that employers set up systems in which their employees help to create and select the option of their choice. Perhaps more than any other chapter, this one emphasizes that there is no one right way to resolve anything and that an individual’s freedom to create his or her own dispute resolution process is a prerequisite for a successful system within an organization.

4

The Courthouse and Alternative Dispute Resolution

FRANK E. A. SANDER

Introduction

► This chapter introduces alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms and the ways in which they can be further integrated into the court system. I will start with an overview of dispute resolution and then focus on some specific processes within the court system. I use three concepts to examine disputes and their resolution: the dispute pyramid, the process spectrum, and inside-the-court and outside-the-court mechanisms.

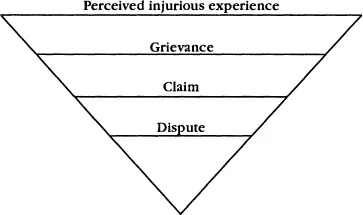

The Dispute Pyramid

The dispute pyramid (Figure 4.1) is an inverted pyramid. At the top of the pyramid is what Bill Felstiner, Richard Abel, and Austin Sarat (1980-1981) call perceived injurious experiences (PIES); a person feels hurt about something. The next level of the pyramid is the identification of a culprit, the person who is responsible for the injury. There is now a grievance against someone. As you move down the inverted pyramid, the injured party would make a claim against the culprit. However, not all people make claims. For example, you might want to take some sort of action against your employer if she or he transfers you to a job that you do not like. But you realize that it would be difficult to get another job and that you need to get along with your employer, so you do not make a claim. It all depends, in dispute resolution jargon, on what alternatives you have available to you, what your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) is. Not everybody who has voiced a grievance will make a claim. If a claim is made, it will likely become a dispute. But not all claims become disputes because some culprits believe that the injured party is correct and agree to compensate them.

Figure 4.1. The Dispute Pyramid

One of my students who works at the Harvard Mediation Small Claims Program told me of a case she was attempting to mediate. After identifying herself as a mediator and explaining what a mediator does, the defendant responded, “The plaintiff is absolutely right, I owe him that money.” My student was very upset because she did not have a chance to mediate the case, which shows you that we are not always trying to settle disputes, but sometimes trying to learn how to mediate. Clearly this is a claim that did not become a dispute, because the respondent accepted the claim.

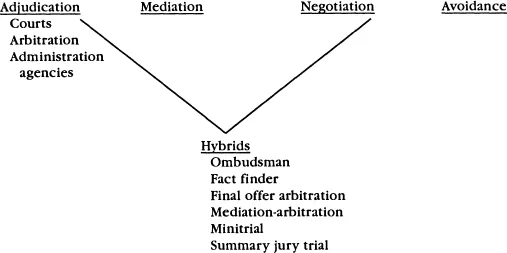

Figure 4.2. The Process Spectrum

Once we have a genuine dispute, there are many alternatives available to resolve them. Some disputes go to court, where a variety of mechanisms are used. Others go to an assortment of noncourt complaint mechanisms such as labor arbitration, ombudsmen, and consumer complaint mechanisms such as the Better Business Bureau. Some of these cases eventually wind up in court, but most of them do not.

What can be learned from the dispute pyramid is that the courts are used to resolve only a tiny proportion of people’s perceived injurious experiences. Law schools should not be spending all their time on such a small part of the dispute resolution universe. We are, therefore, trying to convince law schools to spend more time focusing on alternative methods of dispute resolution. We are making gradual progress; increasingly, some of these concepts are being introduced. Courses are being offered in negotiation, mediation, and other forms of alternative dispute resolution.

The Process Spectrum

Another useful tool for examining dispute resolution processes is the process spectrum (Figure 4.2). As one moves along the spectrum from right to left, third-party involvement increases. At the extreme right end there is avoidance which is comparable with the level of the dispute pyramid at which a person decides not to voice a claim. Once a claim becomes a dispute, there are several processes that can be used to resolve it. The most common form of dispute resolution is bargaining or negotiation, a field that has grown considerably over the past 15 or 20 years. There is increased third-party involvement in the resolution as you move along the spectrum from negotiation to mediation and finally to adjudication. There are essentially three types of adjudication: adjudication in courts, arbitration, and that in administrative agencies.

A dividing line exists between negotiation and mediation. To one side of the line people handle disputes on their own, either by not voicing a claim or by negotiating. The processes to the left of the line—mediation and adjudication—involve third parties. However, the really important dividing line exists between mediation and adjudication because mediation, although a third-party process, is really more akin to negotiation than to adjudication. I think the key to understanding dispute resolution is understanding the significance of the dividing line between mediation and adjudication.

In teaching mediation, I ask people to take a relatively simple problem such as an uncomplicated divorce or a simple dispute between two neighbors; I then ask them first to resolve the dispute by adjudication and then by mediation. Think about what happens.

When people play the roles of the disputants as well as the third party, they feel entirely different in the two processes. In mediation, the disputants feel much more in control of the process. They come up with and, therefore, own the result; the mediator does not tell them what the answer is. The mediator is simply a catalyst. In adjudication, the disputants have to be very careful not to alienate the adjudicator, because she or he can impose a solution on them. Their whole argumentation is entirely different. They play up to the adjudicator, which is what happens in most courts between the lawyers and the judge.

The third party also feels different in these two processes. In mediation, the third party typically feels less responsibility for the substance of the agreements, although this depends on the type of dispute. This raises the issue of the ethical responsibility of the mediator. Many argue that the primary criterion for judging a mediation is whether the parties are satisfied with the outcome, not whether the results are fair and well-reasoned and serve as a precedent for the future, criteria that would apply in judging a court decision. Susskind has argued that, at least in the public sector, mediation outcomes should be judged by whether they are fair, efficient, wise, and stable.1

In the mediation chapter of the book Dispute Resolution (Goldberg, Sander, & Rogers, 1992) there is a hypothetical Socratic dialogue that addresses this issue. Does the mediator have the same kind of social responsibility as the adjudicator in producing an ethical decision? Should the mediator withdraw if she or he strongly disagrees with and does not wish to bless an arguably unfair decision with which both parties are satisfied? The conclusion is that the ethical responsibility of a mediator depends on the nature of the relationship between the parties and the kind of dispute that is involved.

In the environmental area, and perhaps also in the family area, there is generally a public interest in the outcome of the dispute, and the parties themselves are often not sophisticated; often too, there are bargaining imbalances between the parties. In these cases, the mediator may have an ethical and social responsibility to ensure a fair decision, similar to, if not the same as, a judge. By contrast, in the labor sphere, where you have sophisticated people who regularly deal with each other, most mediators feel that the goal does not extend much beyond producing a result with which both parties are satisfied.

Before I leave the world of mediation, it is worth noting that there are two distinct forms of mediation. In one, which may be termed rights based, the mediator looks to the rights that the disputants would have in court, and with that guideline as a benchmark, tries to help the disputants resolve the dispute within those parameters. For example, in a personal injury case, such a rights-based mediator might seek to predict the likely result in court if the case went to trial and then use that information to help the parties reach an acceptable settlement.

A different approach is one that focuses on the interests, or needs, of the parties. Take, for example, a dispute between two partners of a small manufacturing business, one of which has contributed the capital and the other an invention. Assume that the inventor partner has come forth with a product that was initially rejected by the capital partner, but that the latter now wants to appropriate this product for the partnership. The rights-based approach would look to the outcome if this case were to go to court and seeks to use that shadow to facilitate a settlement. An interest-based approach would look to the needs of the parties (such as the inventor’s need to exercise his creative powers while the supplier of capital wants to make sure that the inventor does not use the business to feather his own nest).

Inherent in this approach is the desirability of fashioning a new relationship between the two disputants that will address the general question of the inventor’s relation to the company with respect to future inventions and that may incidentally yield an acceptable solution to the present dispute. For example, regardless of what a court might decide in this situation, the disputants after canvassing various options might decide that a fair solution in such cases would be for the inventor to get 25% of the royalties off the top and then to contribute the remainder to the partnership. Or they may decide to formulate a much more complex arrangement. But the key point is that mediation will attempt to explore the interests of each disputant and then come up with some accommodative resolution.

Hybrid Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Let us return now to the process spectrum. Galanter (1984) at the Wisconsin Law School coined the term litigotiation. He says that most cases are really disposed of through litigotiation, a combination of litigation and negotiation. There are many hybrid processes that combine some aspects of the primary processes discussed above, including fact finder, neutral expert, minitrial, summary jury trial, mediation-arbitration, and final offer arbitration. All are described in this chapter.

Fact Finder. A fact finder combines some aspects of mediation and arbitration. A fact finder is similar to a mediator in that she or he is a disinterested third party who determines the facts but has no authority to impose a decision on the parties. However, a fact finder, based on his or her conclusions from the case, can weigh in on the side of one of the disputants. For example, a fact finder in a labor dispute can find that the union is correct in saying that a fair wage to pay for a particular job is $7 rather than $5 an hour. The effect of such a finding is, therefore, similar to quasi-adjudication.

Final Offer Arbitration. Final offer arbitration is a hybrid of negotiation and adjudication used in baseball player salary disputes and in public sector bargaining, particularly for the police and fire departments. Each side comes up with its best offer. The third party must pick one of the offers but cannot select a compromise between the two. In form, the process is similar to adjudication or arbitration in that the third party chooses and imposes the outcome. But, in effect, it is similar to negotiation in that it presses the disputants to compromise and make more reasonable demands because they know that the third party will pick the most reasonable offer. It encourages the disputants to come up with their own result, but if they are unable to, it offers a third-party decision as a failsafe.

Mediation-Arbitration. Mediation-arbitration is known in the field as med-arb and is a mechanism commonly used in labor disputes. The process begins with mediation. If the parties cannot settle, the mediator takes off the mediation hat, puts on the arbitration hat, and imposes a solution. Some academics in the dispute resolution field are very troubled by this method, because they think that it commingles two very different processes in a nonconstructive manner. The parties in a mediation often give the mediator information in confidence. If the mediator suddenly becomes a judge, she or he can impose a decision based on confidential information received from one of the parties during the mediation. However, people in the labor field advocate this method and use it all the time. I am reminded of the Maine farmer who, when asked whether he believes in infant baptism, said, “Believe in it? Hell, I’ve seen it done.” Of course, this issue of role confusion can be avoided if the arbitrator is a different person than the mediator, but then there is also a concomitant loss in efficiency.

Another variant, used in South Africa, is call arb-med. There, the neutral, after hearing the case, writes a decision that is then placed in a sealed envelope and put aside. Only if the subsequent mediation fails to produce an agreement is the envelope opened.

Inside-the-Court and Outside-the-Court Mechanisms

I will now focus on a third way of looking at dispute resolution by considering inside-the-court and outside-the-court mechanisms. There are many outside-the-court dispute resolution mechanisms that are used regularly: labor arbitration, commercial arbitration, consumer protection mechanisms such as the Better Business Bureau, internal grievance mechanisms in prisons and hospital...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- I. Frameworks for Effective Negotiation

- II. Applying Mutual Gains to Organizations

- III. Perspectives on Individual Negotiators

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Negotiation by Lavinia Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.