![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Historical Overview of Disasters and the Crisis Field

Priscilla Dass-Brailsford

Hurricane Katrina cut a wide swath of destruction across the Gulf Coast at the end of August 2005. In the span of 5 hours, the storm devastated approximately 90,000 square miles in the Gulf Coast areas (Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi) and displaced hundreds of thousands of people, leaving much of New Orleans under water for several weeks. The reconstruction process has taken several years at an estimated cost of $81.2 billion (U.S.), making Hurricane Katrina one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history. However, U.S. cities have arisen from massive devastation before; the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and Hurricane Andrew in 1992 are a few examples of events that have challenged the resources of other cities in the past. In this chapter, several major disasters are discussed to provide a historical backdrop to the crisis and disaster field. These disasters offer important lessons that future disaster responders are urged to heed. Finally, this chapter provides an overview of the major agencies involved in disaster planning, management, and response.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

Provides a history of the evolution of the crisis and disaster field;

Reviews in depth some of the worst disasters, both nationally and internationally in terms of the contributions made to the disaster field; and

Describes the development of major disaster and crisis response organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, Federal Emergency Management Agency).

BACKGROUND

Disasters have occurred long before recorded history. For example, in approximately 1500 B.C., the Mediterranean Stroggli island blew up after a tsunami nearly eradicated the Minoan civilization. The area is now called Santorini, and Plato referred to it as the site where the city of Atlantis disappeared under the waves (Crossley, 2005). In 3000 B.C., a major global paleo-climate event, of which little is known, appears to have affected sea-level vegetation and surface chemistry. It is speculated that this disaster may have been the flood recorded in the Old Testament of the Bible. About 65 million years ago, a space rock hit the Earth and wiped out dinosaurs and countless other animal species. Many other natural disasters occurred globally prior to Hurricane Katrina. Similar to Hurricane Katrina, they were cataclysmic events that reshaped government policy and captured the nation’s empathy for generations.

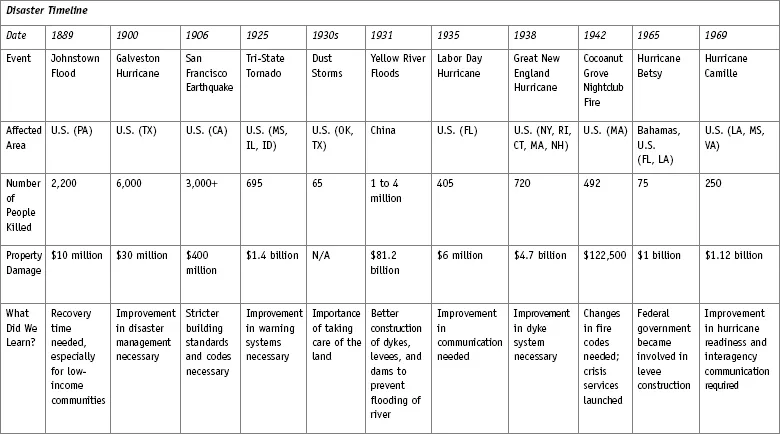

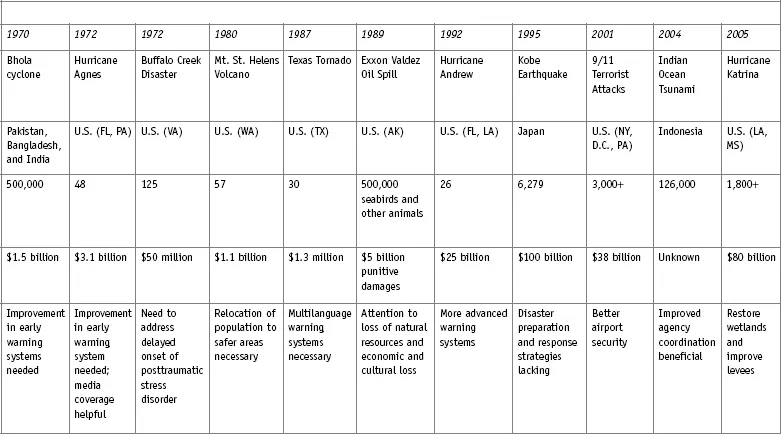

The disaster timeline lists some of the significant disasters that occurred in the world over the past century (see below). The lessons learned paved the way for major changes in the delivery of disaster and crisis services as we know it today.

These disasters are reviewed because of the impact they had in terms of loss of life and property damages, as well as the contribution they made in the development of the crisis and disaster field.

The Great San Francisco Earthquake (1906)

On April 18, 1906, residents of San Francisco were awakened by an earthquake that would later devastate their city. The magnitude of the main tremor extended from 7.7 to 7.9 on the Richter scale, the result of a 296-mile rupture along the 800-mile San Andreas fault line that lies on the boundary between the Pacific and North American plates. During the earthquake, the ground west of the fault line moved northward. The point where the most extreme shift occurred measured 21 feet across. Seismologists estimated the speed of this rupture to have been 8,300 mph northwards and 6,300 mph southwards. Residents from Los Angeles to central Nevada reported feeling the effects of the earthquake, which was later rated 8.3 on the Richter scale, developed in 1935 to measure the magnitude of earthquakes.

The earthquake lasted approximately 1 minute but was a secondary concern to the destructive 4-day fire that followed. Broken water hydrants made fighting the fires a challenge, and the fire resulted in the destruction of almost 500 city blocks. Damages were estimated at $400 million at the time; more than 225,000 people were left homeless, and the death toll was approximately 3,000. Scientists predict a 62% probability of a larger earthquake (6.7 or more in magnitude) occurring in the Bay Area in the next 30 years.

Many new developments in the disaster field occurred as a result of the San Francisco earthquake and efforts by the Californian governor George Pardee, who put together a task force of renowned scientists to investigate the causes of the earthquake. Four years after the disaster, the Lawson (1908/1969) report, which laid the foundation for what we know about earthquakes today, was produced. The exhaustive report was favorably received upon its publication and continues to be highly regarded by seismologists, geologists, and engineers concerned with earthquake damage to buildings; the report stands as a milestone in the development of understanding earthquake mode of action and origin.

Thus, the study of seismology grew rapidly after the San Francisco earthquake and the data collected after the catastrophe transformed the field into a respected science that would prove invaluable in predicting future earthquakes and understanding their impact; the 1906 disaster marked the birth of earthquake science in the United States.

Given the exorbitant financial costs incurred after the disaster, earthquake preparedness became a major priority for city officials and local businesses throughout the city of San Francisco. Unfortunately, in their haste to restore economic and pre-disaster functioning, more emphasis was placed on rebuilding quickly rather than securely. As a result, building codes were not modified to accommodate the possibility of a similar or worse earthquake occurring. Despite the Bay Area’s vulnerability to earthquakes, thousands of homes today do not meet current earthquake safety standards, making the city no less safe today than it was in 1906. In fact, its vulnerability is greater for several reasons: It is situated in the proximity of two active fault systems, its population has doubled to almost 800,000, and its economy ranks as the 21st largest in the world. As a result, if a major earthquake occurred today, a larger number of structures would collapse rather than sustain damage; this would increase the potential human death toll tremendously.

Hurricane Betsy (1965)

Hurricane Betsy was the first hurricane in the United States to cost a billion dollars in estimated damages, earning it the infamous title “Billion Dollar Betsy.” The hurricane gained momentum as it came over the Florida Keys on September 7, 1965, emerging as a Category 3 storm after crossing Florida Bay and entering the Gulf of Mexico. It came ashore at Grand Isle, south of New Orleans, where it caused immense property damage before traveling upriver, triggering a 10-foot rise in the Mississippi River. The hurricane continued to move in a northwesterly direction, grew into a Category 4 storm with 155 mph winds, and caused major storm surges in Lake Pontchartrain, north of the city of New Orleans. These high storm surges caused an overtopping of the levee system so that water reached the eaves of several houses in the Crescent City. Hurricane Betsy was the first hurricane to directly hit New Orleans. The hurricane killed 76 residents in New Orleans, most of whom lived in the Ninth Ward area where water reached the highest level. Extreme flooding also occurred in the St. Bernard’s Parish neighborhood of New Orleans. Sadly, history repeated itself many years later in 2005, when Hurricane Katrina wreaked similar devastation in both these neighborhoods of New Orleans.

At the time of the disaster, the federal government was minimally involved in the construction of levees and floodwalls; this responsibility fell within the purview of local government agencies. However, the devastation caused by Hurricane Betsy prompted the federal government to become more actively involved in disaster management. The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers was authorized to build 16-foot-high levees to protect New Orleans from future disasters, even though it was not clear whether such levees would sufficiently protect the city. That question was answered with alarming clarity when Hurricane Katrina washed ashore in 2005.

Although the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers has overseen the construction of millions of dollars of federal hurricane protection projects in New Orleans, parts of the metropolitan areas of New Orleans do not meet federal flood protection standards. Budgetary constraints have limited the Corp’s ability to construct and repair constantly sinking levees, while the city’s vulnerability to flooding has dramatically increased in recent years. The construction of 120 miles of levees and floodwalls, initiated before Hurricane Katrina and costing approximately $740 million were predicted to provide more than $11 billion in storm damage reduction benefits. Since Hurricane Katrina, the cost of this project has risen to $2 billion.

Hurricane Camille (1969)

As a Category 5 hurricane, Camille was recorded as one of the strongest and most intense storms to make landfall in the United States. Unlike most hurricanes, it struck at its greatest intensity after entering the Gulf Coast from the Caribbean Sea on August 16, 1969. Hurricane Camille first made landfall at the mouth of the Mississippi River on August 17, accompanied by 200-mph winds. The devastation in the southern Mississippi region was astounding; property and other building structures from Ansley to Biloxi completely disappeared under the storm’s wrath, and only foundation slabs remained as reminders of where buildings had once existed.

Hurricane Camille’s 22.6-foot tidal surges were the highest recorded in U.S. history by the Army Corp of Engineers. As the hurricane moved inland into the southeastern states, the intensity of the storm weakened, but flooding increased and roads, bridges, and buildings were washed away. Devastating flash floods and landslides along the Blue Ridge Mountains destroyed many small communities and caused more than 100 deaths in the states of Virginia and Tennessee. Overall, the best estimate of the number killed by the hurricane was 255 persons. About 50 to 75 people were never found, and the total damages from the storm were estimated at $4.2 billion.

Pielke and Pielke (1997) present two important lessons that Hurricane Camille delivered in terms of testing the nation’s level of disaster preparedness and identifying areas for improvement. First, they indicate that hurricane preparedness should be viewed as the “cost of doing business.” Waiting for a storm to occur to demonstrate a city’s level of preparedness is futile. When a hurricane makes landfall, it results in extreme disruption; communication, power, transportation, and other necessary infrastructures are destroyed or malfunction. Second, decisions made under disaster conditions have to be made quickly; therefore, advanced planning is critical and establishing relationships and other important linkages prior to the disaster supports this goal. Decisions can then be made quickly, based on prior discussions and long-standing relationships. With Camille, coordination between government agencies and state and local officials was enhanced because of such pre-existing plans.

Hurricane Agnes (1972)

Hurricane Agnes blew across the Florida panhandle on June 19, 1972, and scurried up the Atlantic coast into Pennsylvania on June 22, 1972. Although only a Category 1 hurricane when it hit Florida, the rainfall produced by the storm made it more destructive than previous hurricanes. At the time, it was identified as the costliest disaster in U.S. history. Twelve states were devastated before the hurricane made landfall in Pennsylvania, where it became known as Pennsylvania’s worst disaster: Forty-eight deaths occurred in the state; 222,000 residents became homeless; and damages were estimated at $2.1 billion. The overall estimated damages from the storm were $3.1 billion and 117 people were killed.

The hurricane produced 18 inches of rain over 2 days, and the subsequent flooding caused the evacuation of entire towns. A bold prediction by the National Weather Service in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, that floodwaters would overtop the 3-foot-high levees that were built in 1936 around Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, resulted in an orderly evacuation of 100,000 people; this ultimately saved many lives. There were many similarities between Hurricanes Agnes and Katrina: The rushing waters of Agnes tore out a section of a cemetery near Wilkes-Barre, causing 2,000 caskets to be washed away and leaving body parts strewn in residential areas. Returning residents found 5-foot-high watermarks above the first-floor windows of their homes. Cars had floated away and garbage and debris littered the streets. Although advanced, early warning systems were not available at the time, extensive media coverage played a major and supportive role in preparing the public for an effective evacuation.

When Vice President Agnew visited the hurricane-affected area 10 days after the storm had made landfall, disaster victims were still waiting in line for temporary housing at Red Cross shelters. Thousands of disaster victims continued to live in federal trailers a year later. In addition, there were major communication gaps between state and federal agencies of government about which expenses would be reimbursed by the federal government (Miskel, 2006). First responders and Red Cross volunteers reported a similar situation developing in the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina. Much blame was placed on people who did not evacuate fast enough, although they had just a few hours of advance warning. Today, improved technology in advance disaster warning systems provides at least 12 hours’ notice. However, despite this advanced warning capability, 33 years later, survivors of Hurricane Katrina faced a similar situation to the survivors of Hurricane Agnes.

The Texas Tornado (1987)

On May 22, 1987, a violent, multiple-vortex tornado, with winds of 207 to 260 miles per hour devastated Saragosa, Texas, a community of approximately 5,200 people in southwest Texas. The tornado inflicted widespread damage throughout the town. The worst damage occurred in residential and business areas where property and other building structures were completely destroyed. Thirty people were killed and 131 injured. Among the destroyed buildings was a community hall in which about 80 people had gathered for a preschool graduation ceremony; the disaster took 22 lives, and approximately 60 pe...