This is a test

- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Arthur Asa Berger elucidates narrative theory and applies it to readers' everyday experiences with popular forms of mass media. This unique book demonstrates how to interpret narratives while presenting the analysis in an accessible manner.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Narratives in Popular Culture, Media, and Everyday Life by Arthur A, Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Cultura popular. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Nature of Narratives

We seldom think about it, but we spend our lives immersed in narratives. Every day, we swim in a sea of stories and tales that we hear or read or listen to or see (or some combination of all of these), from our earliest days to our deaths. And our deaths are recorded in narratives, also—for that’s what obituaries are. As Peter Brooks (1984) puts it: “Our lives are ceaselessly intertwined with narrative, with the stories that we tell, all of which are reworked in that story of our own lives that we narrate to ourselves. . . . We are immersed in narrative” (p. 3).

In this book I will discuss a number of topics related to narratives. What are narratives? How do they differ from other kinds of literary works? Why are they important to us? What roles do narratives have in our lives? How do narratives function?

I should note that I adopt here the term used in literary theory to refer to creative works of all kinds, text. This enables me to talk about everything from comic strips to novels without having to repeat myself all the time and signifies that what is being discussed, the text, is some kind of a work of art—low or high, popular or elite, for children or adults. Text is an abstract and general term that can be very useful, especially when one is dealing with theoretical matters.

We are exposed to narrative texts from our earliest days, when our mothers sing lullabies and recite nursery rhymes for us. The songs and simple verse we learn when we are small children are narratives. For example, take the nursery rhyme about Humpty Dumpty:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the king’s horses

And all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the king’s horses

And all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again.

This is a narrative text—a simple one, but a narrative nevertheless. So are fairy tales, adventure stories, biographies, detective stories, and science fiction stories. Television is a narrative medium par excellence. It is possible to see the evening news shows on television as narratives (or as having many narrative elements in them), although the people who create newscasts would probably find that idea somewhat farfetched. Comic strips are narratives, but single-frame cartoons are not. Such cartoons give us a moment in time, but they contain no sequence, generally speaking.

Although narratives may be simple or complex, understanding how they function and how people make sense of them are subjects that are extremely complicated and that have perplexed literary theorists for centuries—from at least as far back as Aristotle’s time to the present.

Speculations About Humpty Dumpty

Let’s consider the information the little nursery rhyme about Humpty Dumpty gives us.

1. Humpty Dumpty. Humpty Dumpty is the name of a character, the hero, whose “tragic fate” is the subject of the story. We also have an example of personification, as an egg is turned into a person (although the rhyme does not specify that Humpty Dumpty is an egg, this element of the story is understood through tradition and reinforced by illustrations that have accompanied the rhyme in countless publications). There is also an internal rhyme in the name (the repetition of “umpty”) that adds emphasis.

Interestingly, a case can be made that Humpty Dumpty isn’t just a nonsense name. The word hump refers to a rounded protuberance of some kind, and dump can refer to the emptying out of a container (as in dump truck); thus “Humpty Dumpty” is a rounded protuberance that empties itself out—which is precisely what happens in the story. Of course, both hump and dump have other meanings as well, but without stretching things too much we can see a relationship between Humpty Dumpty’s name and what happens to him.

2. Sat. Here an action or, perhaps more accurately, an activity is described. Humpty Dumpty is doing something—in this case sitting on a wall. Something is about to happen, so we can say that we have “rising action” here—though we know it will soon be falling action.

3. On a wall. Here we have location and spatiality. Where is Humpty Dumpty sitting? On a wall—though we don’t know where the wall is. Walls generally have some height, so we have reason to believe (and we know from traditional illustrations of the rhyme) that he is quite a distance from the ground.

4. Humpty Dumpty. Once again the name of the main character appears. Such repetition is a way of generating emphasis.

5. Had a great fall. With this description of more action, Humpty Dumpty’s crisis is related. This is the crucial event in this simple story The word fall can be connected to many different kinds of events, from the fall of Adam and Eve to other kinds of falling, sometimes good (falling in love) and sometimes not so good (falling into debt, falling behind in payments).

6. All the king’s horses. This part of the rhyme is puzzling. What do the king’s horses have to do with anything? The line suggests, implicitly, the power of the king and the nature of the king’s commitment. He committed all his horses to a task. The horses actually are secondary characters in this story, as we shall see.

7. And all the king’s men. This line adds emphasis to the one preceding it through repetition, and together these two lines suggest that even if the king committed all his resources to the matter of putting Humpty Dumpty together again, it still could not be done. There are limitations, then, on what kings can do and, by implication, limitations on what anyone can do in given situations. The king’s men and, by inference, the king are actually secondary characters in this tale. The two lines “All the king’s horses / And all the king’s men” represent a response to Humpty Dumpty’s fall and can be thought of as part of “falling action.” The main event has occurred, other secondary things are going on, but in a sense the story has had its crisis.

8. Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again. With this line we reach the “tragic” resolution of the story. Nobody—not even the king, with all his horses and all his men—could put Humpty Dumpty together again—nobody can reconstruct an egg that has fallen and splattered.

We can see that even a simple nursery rhyme has the basic components of a narrative, even if they are elemental in nature. Such narratives are well suited for the intellectual capacities and emotional development of their target audience—young children. As we get older and grow more mature, we become interested in narrative texts that are more challenging and more complicated. These texts require more of us; we need more refined sensibilities and more information, as well, to understand and appreciate them.

What Is a Narrative?

A narrative is, as I have suggested, a story, and stories tell about things that have happened or are happening to people, animals, aliens from outer space, insects—whatever. That is, a story contains a sequence of events, which means that narratives take place within or over, to be more precise, some kind of time period. This time period can be very short, as in a nursery tale, or very long, as in some novels and epics. Many stories are linear in structure, which may be represented as follows:

A → B → C → D → E → F → G → H → I

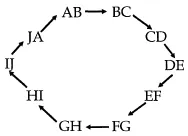

Figure 1.1. The Circular Nature of La Ronde

In this case, A leads to B, which leads to C, and so on, until the story ends with I.

Stories need not always follow straight lines, however; they can also move in circles or in other configurations. Consider the play La Ronde (The Circle), which can be diagrammed as follows:

AB → BC → CD → DE → EF → FG → GH → HI → IJ → JA

However, a diagram of La Ronde that shows its circular nature, such as that in Figure 1.1, gives a better idea of what happens in the play. La Ronde has a plot in which the motion is circular: A has a relationship with B, B has a relationship with C, and so on until J has a relationship with A and the circle is, so to speak, closed.

The 10 “dialogues” or scenes of La Ronde are described by Arthur Schnitzler (1897), the author of the play, as follows:

- AB: the Whore and the Soldier

- BC: the Soldier and the Parlour Maid

- CD: the Parlour Maid and the Young Gentleman

- DE: the Young Gentleman and the Young Wife

- EF: the Young Wife and the Husband

- FG: the Husband and the Little Miss

- GH: the Little Miss and the Poet

- HI: the Poet and the Actress

- IJ: the Actress and the Count

- JA: the Count and the Whore

Thus the circle is complete when the Count and the Whore have their dialogue.

Although Schnitzler calls his scenes “dialogues,” various actions also take place in each scene, so that term is not quite accurate. There are, of course, plays in which almost no action is shown—in which actors (functioning as narrators of sorts) read letters between characters and that sort of thing—but most of the time plays depict actions; that is, characters do other things as well as talk. Talking, of course, can also be construed as a kind of action.

Notice that I used the term plot above regarding La Ronde. Is there a difference between a plot and a story? If so, how does a plot relate to a story? I will discuss this matter later, but I mention it here to show that there are complications that we must deal with when discussing narratives.

The Differences Between Narratives and Nonnarratives

As I have stated, narratives, in the most simple sense, are stories that take place in time. What else might we say about them? One topic we should deal with involves the way narratives differ from nonnarratives. Consider, for example, the story about Humpty Dumpty and a drawing of Humpty Dumpty shown sitting on a wall. In the story we find out what happened to Humpty Dumpty—he had a fall and couldn’t be put back together again. (This simple story, I might add, is used endlessly by writers and speakers to make points about the frailty of institutions and about the nature of life; sometimes, Humpty Dumpty serves to teach us, we tear things apart and find that we can’t put them back together again. So we learn something from this tale.) In the picture, we see Humpty Dumpty sitting on the wall and that is all. We capture a moment in time, but we do not see any sequence.

Drawings, paintings, photographs—anything pictorial, in one frame—are not generally thought to be narratives, though they may be parts of narratives that we all know and are familiar with. For example, comic strips are made up of frames; each frame captures a moment in time, and the collection of frames takes place in time. Drawings of Humpty Dumpty are part of the common knowledge of young children in England and the United States (and perhaps elsewhere); when they see a picture of Humpty Dumpty sitting on the wall, they know what will happen because they’ve been exposed to the nursery rhyme as part of their childhood culture.

Although some paintings contain enough information that they can be read as narratives, with the viewer looking at one part of the painting and then moving on to another, generally speaking, pictures that stand alone are not understood to have narrative content.

Narration and Narratives

A narrator is someone who tells a story. The word comes from the Latin narratus, which means “made known.” A narrator makes something—a story—known, whether one created by another or by the narrator him- or herself, as in the case of a storyteller. Take the nursery rhyme we’ve been discussing, “Humpty Dumpty.” Technically speaking, this story is narrated.

Humpty Dumpty is an object, but not a subject. That is, he is someone whose tragic fa...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Nature of Narratives

- 2. Theorists of Narrativity

- 3. Narrative Techniques and Authorial Devices

- 4. A Glossary of Terms Relating to Narrative Texts

- 5. Dreams: A Freudian Perspective

- 6. Fairy Tales

- 7. The Comics

- 8. The Macintosh “1984” Television Commercial: A Study in Television Narrativity

- 9. The Popular Culture Novel

- 10. Radio Narratives: A Case Study of the War of the Worlds Script

- 11. Film Narratives

- 12. Narratives and Everyday Life

- Appendix: Simulations, Activities, Games, and Exercises

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- About the Author