![]()

1

Impact Schools

I’ve had the pleasure of working with some astonishingly good people from the Beaverton, Oregon, School District. Three times a year, on their own time, instructional coaches Susan, Michelle, Jenny, Lea, and Rich come to the Kansas Coaching Project at The University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning to collaborate with my colleagues and me. They come for one reason: they want to become better instructional coaches.

Our meetings are highlight days for me even though what we do is fairly simple. Most of the time, the coaches watch themselves doing their work on video1 and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of what they see themselves doing. This work is not easy. The conversations demand that the coaches be courageous, supportive, open-minded, reflective, and above all, committed to learning. Together, we take an honest look at what is working and what we can do better. They watch themselves coaching; our research team watches our ideas in action to see what works and what needs to be refined. Each day is filled with substantial reflective comments, kind words, hard truths, laughter, fun, energy, and, mostly, learning.

During one of our meetings, I decided to document what was happening, so I asked everyone to write down a few words that described how they felt. What they wrote offers some insight into what we experience.

- Learning, exploration, humbling, in awe, affirming, reflection, imperative for growth/change, helpful

- Sweaty, shaky, good, validation, curious, aha moments, respected and collegial, safe, insightful, nervous

- Pride, laughter, nervousness, sincerity, humility

- Sweaty, nerve-wracking, exposing, vulnerable … yet comforted, validated, supported, encouraged, learning a ton, silence is golden

Their words surface what makes our sessions together so significant—we are energized by learning with each other. Since we cannot avoid reality (it is right on the screen for all to see in the recordings of coaching sessions), our talk focuses on issues that really matter. However, because we like and respect each other, because as a community of learners we have a stake in each other’s well-being, we treat each other kindly and supportively, and that tenderness toward each other makes it possible for us to feel safe together. With a clear picture of reality and a safe setting, we learn an enormous amount.

The experiences of the Beaverton coaches put professional learning at the heart of our talk. We leave our conversations smarter, more empowered, and more aware of our mutual humanity. Learning fuels our talk and makes us more alive. This kind of learning—learning that is safe, humane, empowering, and guided by a vivid awareness of current reality—should be a driving force for humanizing professional learning in schools. Indeed, I believe that schools will only become the learning places our children deserve when our professional learning embodies this kind of humane learning. I’ve written this book to suggest how such learning might occur.

The Best Jobs

Most of us can think of a few elements we’d like to experience in a fulfilling, productive, and happy career. The best jobs involve frequent, supportive, encouraging, and warmhearted conversations like those created by the instructional coaches from Beaverton. The best workplaces are electric with learning, with the buzz of new ideas, the inherent joy of growth. In the most rewarding work, we use our knowledge, minds, and hearts to do something that contributes significantly to the greater good.

Teachers should have many opportunities for this kind of meaningful work, involving positive conversations, personal learning, and contributing to the greater good. By continually exploring new ways of reaching students, teachers can see their classrooms as learning laboratories where their own professional learning mirrors their students’ academic and life learning. By empowering students to be masters of language, to transcend their social status, and to love learning, educators have a marvelous opportunity to create a brighter future for their students and society at large.

Unfortunately, far too often, teaching does not feel like the best job in the world. Too frequently, conversation between educators is negative and unpleasant, with more eye rolling than nods of appreciation. Too often, educators, worn down by continual social and professional criticism (from politicians, journalists, parents, administrators, students, and others), slowly stop trying to improve. Defeated by the roadblocks that keep them from having the impact they hope to have on students, and naturally determined to protect their self-esteem, educators may adopt a defensive stance, blaming others for their lack of success rather than asking what they and their peers can do to reach more children. Feeling frustrated and defeated, many of these educators give up and stop their own learning. When teachers stop learning, so do students. When schools stop learning, our students and society as a whole suffer.

The Failure of the American School System

During my workshops, I often play a recording of a 15-year-old ninth-grade student, Tyshon, as he struggles to read a few hundred words written well below his grade level. Tyshon is able to sound out most of the words, and bit by bit, word by word, he makes his way through a paragraph about a family of geese, each syllable another mountain to be climbed. At times, Tyshon sighs deeply as he struggles through or mispronounces words such as signaled, immediately, trio, waddle, and children. While Tyshon eventually gets to the end of the paragraph, he has little understanding of what he has just read.

When workshop participants listen to Tyshon read, they quickly become silent. They know that Tyshon, even if he is totally committed to learning, is up against an enormous challenge. Every day, when he sits down to read—and he’ll need to read almost every day in every class— he is reminded of his reading challenges. It is quite possible that he will fail a pop quiz after spending hours on preparatory reading, only to be told, “If you want to pass the class, you’ll need to do the reading.”

I think the workshop participants fall silent when they listen to Tyshon because they know that they have students like him in their school. They also know that he probably isn’t going to make it. Even if he is very committed to graduating high school, he will eventually find his failure too frustrating, and he will drop out.

Unfortunately, Tyshon is not an isolated case. The statistics on students in American schools are frightening. Numerous extensive and comprehensive studies of the U.S. school system make it clear that our schools are not preparing our students to graduate and succeed. Here are just a few of the findings:

- Every year, over 1.2 million students—that’s 7,000 every school day—do not graduate from high school on time (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2005).

- Nationwide, only about 70 percent of students earn their high school diplomas. Among minority students, only 57.8 percent of Hispanic, 43.4 percent of African American, and 49.3 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native students graduate with a regular diploma, compared to 76.2 percent of white students and 80.2 percent of Asian Americans (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2005).

- Only 29 percent of America’s eighth-grade public school students meet the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) standard of reading proficiency for their grade level (U.S. Department of Education, 2007).

- About two-thirds of prison inmates are high school dropouts, and one-third of all juvenile offenders read below the fourth-grade level (Haynes, 2007).

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that the United States ranks 16th out of 21 OECD countries with respect to high school graduation rates (Kirsch, Braun, Yamamoto, & Sum, 2007).

- Among U.S. students, 71 percent told the Public Agenda Foundation that they only do the bare minimum to get by (Hussey & Allen, 2006).

- Fewer than half of all high school graduates are prepared for basic college-level math (Kadlac & Friedman, 2008).

- According to several studies, only one in five minority students who receive a high school diploma are ready to go to college (Williams, 2009).

- Too many new teachers, 14 percent, leave by the end of their first year; 30 percent have left within three years; and nearly 50 percent have left by the end of their fifth year of teaching (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2005).

- Unless current trends change, more than 12 million students will drop out during the course of the next decade—at a loss to the nation of more than $3 trillion (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2005). To put that number into perspective, the president’s proposed fiscal year 2009 budget for the entire federal government—including defense spending, Social Security, health care, education, NASA, and everything else—was $3.1 trillion (Stout & Pear, 2008).

- If the nation had graduated 100 percent of its high school students 10 years ago, the money the additional graduates would have put back into the economy would have covered the entire cost of running the federal government in 2009 (Amos, 2008).

Unmistakable Impact

These data are overwhelming, disturbing, even frightening; and not surprisingly, they have prompted many to seek someone to blame. Democracy, after all, as Laurence J. Peter has stated, is “a process by which the people are free to choose the person who will get the blame” (Lummis, 1996, p. 6).

When it comes to the crisis in schools, most of us have been indicted. Parents, television, central office, the government, the unions, teachers, we are all blamed, and of course the blame is usually misguided and unfair.

Rather than pinning the blame on someone, a more productive approach is to look for ways to make things better. One area we can improve in schools is professional learning. In interviews with more than 300 teachers about professional learning across Canada and the United States, the one finding that surfaces from those conversations is that traditional forms of professional learning (workshops without follow-up) do not make an impact on teaching or student learning.

This book proposes Impact Schools, where every aspect of professional learning is designed to have an unmistakable, positive impact on teaching and, hence, student learning. I am convinced we can radically improve how well our students learn and perform if our schools become the kind of learning places (for students and adults) our students deserve. Students will not be energized, thrilled, and empowered by learning until educators are energized, thrilled, and empowered by learning. When all educators engage in humane professional learning that empowers them to embrace proven teaching methods, we can move closer to the goal of every student receiving excellent instruction in every class every day.

Core Concepts of an Impact School

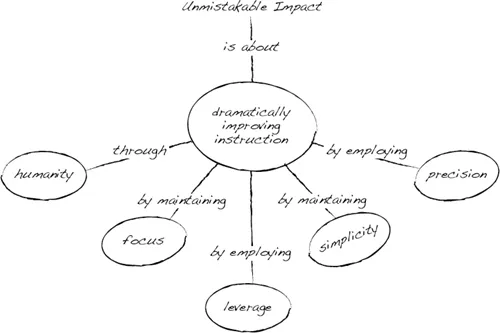

This book provides a simple map for creating the kind of schools our students and our teachers deserve. The professional learning occurring in Impact Schools is built around the following five concepts: humanity, focus, leverage, simplicity, and precision.

Humanity

When leaders and policy makers come face to face with the challenges that exist in American schools, many are tempted to propose and promote draconian methods designed to force teachers to learn new programs and hold teachers accountable for implementing them. Driven by their noble, passionate desire to improve children’s lives, people talk tough about school reform. “We don’t have time to ask for input; our teachers just need to follow the same script,” they might say. “The program provides the script and the pacing guide, and teachers just need to do it exactly how it is spelled out with fidelity.” “Teachers should be ashamed of these scores, and if they refuse to adopt this program, there is no place for them in this school.”

I understand the power of the moral purpose behind these comments, and I share the leaders’ desire to move schools forward as quickly as possible. However, I fear that the strategy of telling teachers what to do and making sure they do often by punitive measures is one of the reasons why schools do not move forward (Payne, 2008). When we take the humanity out of professional learning, we ignore the complexity of any helping relationship, and we make it almost impossible for learning to occur.

Humanity is not a concept we hear a lot of when people talk about professional learning, but I believe the absence of humanity within professional learning is precisely why it frequently fails. What is humanity? We can get a better understanding of the concept by looking at its opposite. According to the standard U.S. dictionary, to dehumanize means to “deprive of positive human values.” Similarly, the Oxford English Dictionary defines dehumanize as “to deprive of human character or attributes.” Wikipedia, on March 5, 2010, defined dehumanization as

the process by which members of a group of people assert the “inferiority” of another group through subtle or overt acts or statements. Dehumanization may be directed by an organization (such as a state) or may be the composite of individual sentiments and actions.

The opposite of dehumanize, then, is to recognize the inherent value of others and to celebrate positive human values, such as empathy, support, love, trust, and respect. Margaret Wheatley (Wheatley & Kellner-Rogers, 1996) describes what a humane way of organizing might look like:

There is a simpler way to organize human endeavor. It requires being in the world without fear. Being in the world with play and creativity. Seeking after what’s possible. Being willing to learn and be surprised … This simpler way summons forth what is best about us. It asks us to understand human nature differently, more optimistically. It identifies us as creative. It acknowledges that we seek after meaning. It asks us to be less serious, yet more purposeful, about our work and lives. It does not separate play from the nature of being. (p. 5)

Professional learning that dehumanizes its participants carries the seeds of its own failure. When a select few do the thinking for others, when people are forced to comply with outside pressure with little or no input, when teachers asking genuine questions are labeled resisters, when leaders act without a true understanding of teachers’ day-to-day classroom experiences, those dehumanizing practices severely damage teacher morale. And when teachers feel disillusioned and damaged by the professional learning they experience, their disappointment, hurt, and unhappiness surface in the classroom and inevitably damage the very children they are there to educate and inspire.

The necessity of putting humanity at the heart of professional learning was well stated by Parker Palmer, in his introduction to The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life:

In our rush to reform education, we have forgotten a simple truth: reform will never be achieved by renewing appropriations, restructuring schools, rewriting curriculum, and revising texts if we continue to demean and dishearten the human resource called teacher on whom so much depends … [nothing] will transform education if we fail to cherish—and challenge—the human heart that is the source of good teaching. (2007, p. 3)

In Impact Schools, educators nourish humanity by working from foundational principles that lead to respectful interchange. Whe...