![]()

1

Begin With the Brain

Interpreting Neuroscience Research

It is often popularly argued that advances in the understanding of brain development and mechanisms of learning have substantial implications for education and the learning sciences. … Neuroscience has advanced to the point where it is time to think critically about the form in which research information is made available to educators so that it is interpreted appropriately for practice.

—Bransford, et al., How People Learn

In the early 1980s I heard Dr. Marian Diamond, a neuroscientist from the University of California at Berkeley, give a keynote address at the annual conference for the California Association for the Gifted. After she had amazed the audience of primarily educators with her findings about “enriched environments,” brain “plasticity,” and the implications for students, she asked the most profound question, to which I still have not discovered a reasonable answer:

“If the brain is the organ for learning, then why aren’t teachers brain experts?”

Twenty-five years ago, I suppose we could put our naïve heads in the sand and profess that the latest brain research, including Dr. Diamond’s, was most often based on studies done on rats, sea slugs, and primates. The research didn’t yet prove anything about human brains. Now, we can’t ignore the incredible discoveries of the last three decades about the brain mechanisms that influence learning and memory:

- Advancements in neuroimaging techniques have allowed researchers to get a glimpse of the brain’s activity as people perform tasks.

- Neurobiologists are helping us understanding the brain’s chemistry and the influences of genetics and the environment—nature and nurture.

- Cognitive neuroscience research sheds light on the impact of emotions on learning and socialization.

- Neurophysiology studies demonstrate the importance of movement, exercise, and nutrition.

As the research surfaced during the 1990s, known as the Decade of the Brain, many noteworthy folks stepped up to the plate to help interpret the findings for the education community. Geoffrey and Renate Nummela Caine, Leslie Hart, Robert Sylwester, Eric Jensen, David Sousa, Susan Kovalik, Robin Fogarty, and Kay Burke were some of the first to refer to brain-compatible learning: the purposeful planning of classrooms, climate, and curriculum around what we knew about how the brain works best.

With the advent of neuroimaging devices in the 1970s (such as PET scans), we began a new journey—one that took scientists for the first time into the inner sanctum of the human brain during the process of learning. … Finally, some of what we have known intuitively all along can now be substantiated. Some teaching methods discourage quality learning, just as some clearly encourage it. (Jensen & Dabney, 2000, p. xi)

In pursuing the answer to Dr. Diamond’s important question, I’ve found out from direct experience that some teachers, while not brain experts in any formal sense, do teach in a way that supports what I will call a brain-compatible classroom. In this chapter, I’ll begin to show you what they’re doing right—usually without even realizing it. We’ve all run into teachers we admire and want to emulate, teachers who get truly extraordinary results from their students. What I’ve learned is that these great teachers are, very often, teaching in accordance with some of the most advanced findings on the workings of the human brain.

One of the best original summaries for brain-compatible learning (also referred to as brain-based learning) is by Geoffrey and Renate Caine (1994) in their book Making Connections: Teaching and the Human Brain. In one of their more recent books, coauthored with Carol McClintic and Karl Klimek (2005), 12 Brain/Mind Principles in Action, they state that,

We argue that on the basis of research and experience that meaningful learning occurs when three elements are intertwined: A state of mind in learners that we call relaxed alertness, the orchestrated immersion of the learner in experiences in which the standards are imbedded, and the active processing of that experience.” (p. xiii)

For the last 12 years, I have adapted these three elements, first referred to by the Caines, and developed them into three basic categories of brain research that can influence educational practices. These big ideas about how we can optimize learning based on neuroscience research are what the rest of this book is based on. The strategies included in the following chapters can all be clustered within at least one of these three key elements.

BEGIN WITH THE BRAIN BASICS

Brain Basics

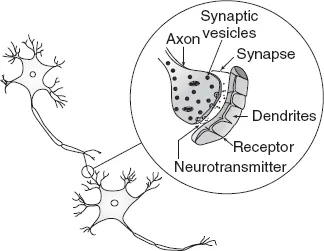

The human brain consists of over 100 billion neurons and about a trillion much smaller glial support cells. The two types of cells split the mass of our brain. Glial cells are not directly involved in information transmission but provide the support and maintenance of the neurons and their trillions of synapses: the points where each connection is made.

Each neuron has a cell body; multiple dendrites that branch out and grow with stimulation, forming the gray matter; and a single axon that typically develops myelin, a white fatty insulation, ending with a collection of synaptic terminals. Neurons communicate through an intricate network of electrochemical interactions. An electrical charge called the action potential is generated within the cell running from the dendrites through the axon to the synapse, the point of contact with another neuron. The myelin sheath acts as an insulator and assures that the charge reaches its goal.

The actual communication between neurons is a biochemical interaction. A variety of neurotransmitters are stored in vesicles at the base of each axon terminal, and with the arrival of the action potential, they are released to travel across the gap to attach to receptor sites on the other side of the synaptic cleft (gap). As the postsynaptic receptors are stimulated, another action potential is generated within that neuron, starting a chain reaction of firing.

Neurons create columns of connections, complex pathways, and form intricate networks and brain systems (see Neuroplasticity, page 13, and Use It or Lose It, pages 14–15). These circuits transport sensory and motor signals to all areas of the body. Specialized regions and lobes are dedicated to movement, sensory input, language, hearing and vision, and so on. The prefrontal lobe, largest in humans, is considered the executive area as it coordinates and integrates the work of all the other regions.

The average adult brain weighs about three pounds. The consistency is like a cube of unrefrigerated butter or cream cheese. It consumes about 20% of the body’s energy when at rest. The internal layers of the brain are surrounded by cerebral spinal fluid that acts as a watery cushion.

Research: The Executive Brain by Elkonon Goldberg, Oxford Univ. Press, 2001.

Practical Application: Magic Trees of the Mind by Marian Diamond & Janet Hopson, Penguin Books, 1998.

Web Site: The Lundbeck Institute: http://www.brainexplorer.org/brain_atlas/

Brainatlas_index.shtml

Three Key Elements of Brain-Compatible Teaching and Learning

1. Less Stress: Create a Safe and Secure Climate and Environment to Reduce Perceived Threat and Danger

The main task here is to create a climate and environment that are conducive to learning by creating a balance of “low threat” and “high challenge” (the Caines use the term Relaxed Alertness).

To create a state of mind that is optimal for meaningful learning, the most important factors are

- Maintaining an atmosphere of trust and respect, where perceived threat is low and balanced with high challenge (i.e., a sense of safety and security that encompasses the mental, emotional, and physical levels);

- Keeping learning joyful and yet rigorous;

- Making sure students know the agenda, purpose, and game plan to reduce anticipatory anxiety;

- Creating a physically healthy and safe environment (sound, light, temperature, basic needs, etc.);

- Orchestrating a socially safe atmosphere where a sense of inclusion is fostered and conflict resolution strategies are demonstrated and utilized;

- Allowing time for reflection, contemplation, and expansion to process new information; and

- Teaching coping strategies for dealing with everyday stress, including stressors from home and outside of school.

If the stress response is activated, it can minimize the brain’s capabilities to learn and remember. The best curriculum and instructional strategies will be useless if the student is in the reflex response. Later in this chapter, I will explain how this physiological reaction takes place and how to orchestrate strategies to avoid it.

2. Do the Real Thing! Provide Meaningful Multisensory Experiences in an Enriched Environment

According to Making Connections (Caine & Caine, 1994), the thrust here is to “take information off the page and the blackboard and bring it to life in the minds of students” (p. 115). The focus is on how students are exposed to content (the Caines refer to this as Orchestrated Immersion). A strong emphasis should be on creating themes and real-world connections around which fragmented curriculum topics can be organized. Students must then have opportunities to do their learning through multisensory, complex, real projects. Classrooms must be environments that combine the planning of key experiences for students and, at the same time, with the opportunity for spontaneity. Experiences must be aligned with students’ developmental stages and prior knowledge. Multisensory, real-world experiences actually promote brain growth and development. Teachers need to

- Pre-assess students’ prior experiences and background knowledge;

- Determine if the content and concept is developmentally appropriate;

- Provide complex, interactive, first-hand learning experiences;

- Make sure content is meaningful and relevant (hook concepts to prior knowledge);

- Provide a wide variety of input and resources; and

- Allow adequate time!

Research on brain plasticity is profound. When exposed to stimulation, the neurons in our brains are prompted to grow dendritic branches that reach out and connect with other neurons. Simply put, this neural network that develops is where our thoughts and memories are “stored.”

BEGIN WITH THE BRAIN BASICS

Neuro “Plasticity”

When the brain is exposed to multisensory stimulation in an enriched environment, neurons are prompted to grow dendritic branches and form new synaptic connections with other neurons. The “father” of the biology of learning and memory, Eric Kandel, was awarded a Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2000 for his early discoveries about neuroplasticity and memory. He discovered that when people learn something, the wiring in their brain changes. Dr. Marian Diamond’s (UC Berkeley) pioneering research proved that environmental enrichment could influence and change the structure of the brain by increasing the cerebral cortex. Her work indicated that being exposed to enriched environments and stimulation could enrich brains at any age.

When babies are born, many neural connections are already in place. By the time children are 10 years old, there will have been a tremendous growth period where some regions of the brain create three times as many connections as they will have later as adults. The brain then goes through a period of intense pruning (arborization). With the onset of puberty, there is another growth surge and subsequent pruning period. While there are basic developmental tendencies and time frames for growth, each brain becomes uniquely wired and shaped. There are some connections that are “experience independent,” which means that you are hard wired at birth or have a genetic predisposition (nature). Then there is “experience dependent” brain wiring that will occur only when we are exposed to experiences that prompt the new dendritic growth and synaptic connections (nurture). No two brains are wired in exactly the same way. Every brain is uniquely formed.

Research: In Search of Memory by Eric R. Kandel, W.W. Norton & Co., 2006.

Practical Application: How the Brain Learns by David Sousa, Corwin, 2005.

Web Site: The Brain Connection http://www.brainconnection.positscience.com

When we have stimulating experiences that are appropriate for our level of development, our brains can grow rapidly. In classrooms, I call this the “Aha! moment.” Marcia Tate’s (2003) popular book, Worksheets Don’t Grow Dendrites!, puts forth the theory that active learning will develop brains and thinking more effectively than a more passive, paper-pencil, worksheet approach.

3. Use It or Lose It! Actively Process New Concepts in a Variety of Ways to Assure Long-Term Retention

In order for students to make sense of an ex...