eBook - ePub

Introduction to Typology

The Unity and Diversity of Language

Lindsay J. Whaley

This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Typology

The Unity and Diversity of Language

Lindsay J. Whaley

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Ideal in introductory courses dealing with grammatical structure and linguistic analysis, Introduction to Typology overviews the major grammatical categories and constructions in the world's languages. Framed in a typological perspective, the constant concern of this primary text is to underscore the similarities and differences which underlie the vast array of human languages.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Introduction to Typology an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Introduction to Typology by Lindsay J. Whaley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART

I

Basics of Language Typology

1

Introduction to Typology and Universals

What is language? On the face of it, the question seems simple. After all, language is so much a part of our everyday experience, so effortlessly employed to meet our impulses to communicate with one another, that it cannot be too intricate a task to figure out how it works. Hidden below the surface of the “what is language” question, however, is a web of mysteries that have taxed great minds from the beginning of recorded history. Plato, Lucretius, Descartes, Rousseau, Darwin, Wittgenstein, and Skinner, to name just a few, have all probed into some aspect of the human capacity for speech, yet none of them were able to explain the origin of language, why languages differ, how they are learned, how they relay meaning, or why they are the way they are and not some other way. Language largely remains an enigma that awaits further exploration.

This is not to say that we have learned nothing or know nothing about our ability to utter meaningful sequences of sound. Centuries of careful observation and experimentation on language have revealed some extraordinary insights into its fundamental properties, some of them quite surprising. Perhaps most significant, language has no analogs in the animal kingdom. Nothing remotely similar to language has been discovered in the vast array of communication systems utilized by the fauna of our planet. Language, it seems, is uniquely human, a fact summarized well by Bertrand Russell (1948) when he exclaimed, “A dog cannot relate his autobiography; however eloquently he may bark, he cannot tell you that his parents were honest though poor.”

In addition to the species-specific quality of language, a second basic notion about language might be highlighted that has become foundational for modern linguistics: There is a basic unity that underlies the awesome diversity of the world’s languages. Whether it be Apache or Zulu or Hindi or Hebrew, there are certain core properties that languages have in common. These properties, often referred to as language universals, allow us to say that all languages are, in some sense, the same.

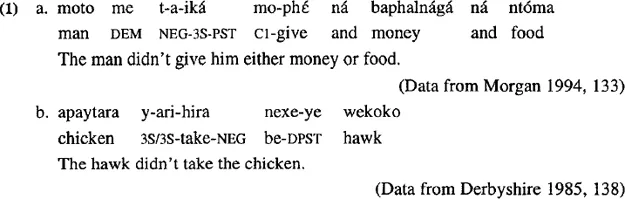

This is, in many ways, an astonishing claim, especially when confronted by the immense variety in the structures of the world’s languages. Consider the following sentences, the first from Lobala (Niger-Congo: Zaire) and the second from Hixkaryana (Carib: Brazil).1

Despite the fact that the two sentences in (1) are both simple negative clauses, they appear to have little in common with each other or with the equivalent English sentences. For instance, the order of words varies: The subject of the Lobala example, moto me (“the man”) occurs at the beginning of the sentence, whereas the Hixkaryana subject wekoko (“hawk”) is located at the end. The negation in Lobala is indicated by an auxiliary verb t-, but in Hixkaryana there is a negative suffix (-hira) on the main verb, -ari- (“take”). Both languages exhibit verb agreement, but in Lobala the agreement suffix (-a) is found on the negative auxiliary, and it only reveals information about the subject (namely, that the subject is third-person singular). In Hixkaryana, the agreement marker is a prefix (y-) rather than a suffix. Furthermore, it is located on the main verb, and it reveals information about both the subject and the object (namely, that both are third-person singular). With regard to these, and many other, differences, the concept of “language universals” may seem hard to accept. Nevertheless, most linguists would claim that there is an underlying homogeneity to language that is far more striking than differences like those just described. Discovering instances of this homogeneity and determining why it exists constitutes one of the major research goals of modern linguistics in general and typology specifically. It also represents the primary concern of this book.

The consensus in linguistics about the underlying unity of language is not paralleled by agreement over how the unity is to be explained or, even more fundamentally, what even constitutes an explanation for the unity. On this point, there are profound philosophical and methodological differences. For example, Noam Chomsky, perhaps the most significant figure in modern linguistics,2 has argued that the unity is due to human biology. In his view, all humans are genetically endowed with a “language faculty,” which is distinct from other cognitive capacities. As children are exposed to the particular language (or languages) of their speech communities, this language faculty directs them in the rapid acquisition of a complex and mature grammatical system. To accomplish this, the language faculty must contain enough information (called Universal Grammar) to ensure that the child can learn a language accurately and learn it in the space of just 4 or 5 years. On the other hand, the innate language faculty must be flexible enough to give rise to the diverse array of structures that we actually find in the world’s languages.

Chomsky has appealed to an extraterrestrial authority on several occasions (e.g., Chomsky 1988, 1991) to drive this point home. Chomsky (1991) suggests that a Martian scientist who visited Earth would reach the following conclusion about a human’s inborn capacity for language:

Surely if some Martian creature, endowed with our capacities for scientific inquiry and theory construction but knowing nothing of humans, were to observe what happens to a child in a particular language community, its initial hypothesis would be that the language of that community is built-in, as a genetically-determined property, in essentials …. And it seems that this initial hypothesis may be very close to true. (26)

In contrast to Chomsky, other linguists have argued that the unity that underlies languages is better explained in terms of how languages are actually put to use. To be sure, languages are all employed for like purposes: asking questions, scolding bad behavior, amusing friends, making comparisons, uttering facts and falsehoods, and so on. Because languages exist to fulfill these types of functions, it stands to reason that speakers will develop grammars that are highly effective in carrying them out. Consequently, under the pressure of the same communicative tasks, languages evolve such that they exhibit grammatical similarities. Language universals, under this “functional” perspective, result from commonalities in the way language is put to work. Closely allied with this view is the proposal that common experiences among humans can account for certain universals in language structure. Lee (1988) articulates this view well:

Despite the fact that I come into contact with quite a different set of objects than a Kalahari bushman, the possible divergence between our experiences in the world is circumscribed by a number of factors independent of us both, and even of our speech communities as a whole. For example, we can both feel the effects of gravity and enjoy the benefits of stereoscopic vision. These shared experiences exert a force on the languages of all cultures, giving rise to linguistic universals. (211-12)

Which explanation for the similarities between languages is right? In all likelihood, the unity of language, and consequent language universals, arises from a slate of interacting factors, some innate, others functional, and still others cognitive, experiential, social, or historical. What this means in practical terms is that there are a number of legitimate ways to approach the question, “What is language?” This book examines the nature of language from a “typological” approach. In the following section, a better sense for what this means is developed.

1.0. Defining “Typology”

What exactly is meant by typology in the context of linguistics? In its most general sense, typology is

| (2) | The classification of languages or components of languages based on shared formal characteristics. |

As a point of departure, it is important to note that typology is not a theory of grammar.3 Unlike Government and Binding Theory, Functional Grammar, Cognitive Grammar, Relational Grammar, or the many other frameworks that are designed to model how language works, typology has the goal of identifying cross-linguistic patterns and correlations between these patterns. For this reason, the methodology and results of typological research are in principle compatible with any grammatical theory. The relationship between typology and theories of grammar is further explored later in this chapter and in Chapter 3.

Having described something that typology is not, we now must come to understand what it is. There are three significant propositions packed into the dense definition in (2): (a) Typology utilizes cross-linguistic comparison, (b) typology classifies languages or aspects of languages, and (c) typology examines formal features of languages. These parts of the definition will be examined one at a time with an eye to better understanding what is involved in performing language typology.

Proposition 1: Typology involves cross-linguistic comparison.

Ultimately, all typological research is based on comparisons between languages. Consider the following data:

| (3) | a. I met the man who taught you French. |

| b. The dog which licked Cora has become her friend. | |

| c. I sent the story to the newspaper that your mother owns. |

From these sentences, we could form the generalization that English relative clauses (in bold type) follow the nouns that they modify (in italics). This description is of import to someone investigating English, but it is incomplete as a typological claim because it is not grounded in a cross-linguistic perspective. Instead, in a typological approach we expect to find a description such as “English is typical in placing relative clauses after the nouns which they modify.” Note that to employ a term such as “typical” properly, one must first have gathered data on relative clauses from a representative sample of the world’s languages. Compiling an adequate sample remains one of the central methodological issues in typological research, an issue to which we return in Chapter 3.

Proposition 2: A typological approach involves classification of either (a) components of languages or (b) languages.

In the first case—classification of components of language—attention is directed toward a particular construction that arises in language—for example, reflexive verbs, oral stops, or discourse particles. Then, using cross-linguistic data, all the types of these specific phenomena are determined. The goal is to better comprehend how this facet of language operates by identifying the degrees of similarity and the degrees of variance that one finds among languages. There is also keen interest in determining whether there are correlations between the various patterns that one finds in a language.

For instance, we might do a typological investigation on oral plosive sounds.4 These are sounds, also called “stops,” that are produced when the airstream is completely impeded in the vocal tract, as in English [p] and [g]. If we were to examine the distribution of oral stops in the world’s languages, we would immediately be struck by the fact that all languages have at least one plosive sound. Thus, we would have discovered a universal about sound systems in human language. It is important to realize that this fact is not a logical requisite for language because we can easily conceive of a language that does not have any oral plosives. Therefore, our empirical discovery that all lan...