eBook - ePub

Diversity in Organizations

New Perspectives for a Changing Workplace

This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Diversity in Organizations

New Perspectives for a Changing Workplace

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The changing demography of the workforce presents challenges and opportunities to individuals and to the organizations of which they are a part. This volume examines how diversity in organizations affords benefits such as a broader talent pool, but at the same time can lead to tension, misunderstanding and, at times, outright hostility.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Diversity in Organizations by Martin M Chemers, Stuart Oskamp, Mark Constanzo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

INDIVIDUAL REACTIONS TO DIVERSITY

1

A Theoretical Framework for the Study of Diversity

HARRY C. TRIANDIS

The future workplace, worldwide, will become increasingly more diverse, and this will be especially true in the economically most developed countries. The reasons are many.

Demographically, the populations of the developed countries are reaching a plateau (Ingelhart, 1990), while those of the developing countries are increasing. Thus migration from the developing to the developed areas of the world is likely to accelerate. This hydraulic model of population change suggests that the developed will accept those from the less developed so as to have services that only those from the poor parts of the world are willing to perform, and those from dense regions will move to the less dense to improve their standards of living. The pressure to do so can be seen in numbers; in the 18th century, the ratio of the gross national products per capita of the rich and poor nations was 2 to 1; in 1950, 40 to 1; in 1990, 70 to 1 (George, 1993). Productivity is accelerating geometrically in certain activities. For example, the introduction of word processors has increased my writing speed, I estimate, by 100%. However, the poor countries are still struggling, largely without such devices.

In addition, globalization means that professionals from the developed parts of the world will live among the workers from the less developed countries. At the same time, environmental degradation will create environmental refugees. The United Nations expects 20% of the population of the world to become environmental refugees by the year 2020 (George, 1993) because of the deterioration of their physical environments, lack of water, and the like. To give you a sense of the enormity of this problem, I will mention one point: The number of environmental refugees in the year 2020 is expected to be the same as the total population of the world was in 1926, when I was born.

The design-production-distribution processes of the 21st century will involve extreme diversity. For example, the design of a product may occur in Germany, financing might be obtained from Japan, execution of the plans might be directed from the United States, the clerical work might be done in Bulgaria, the manufacturing work in China, and the distribution may include a universalist sales force. The interfaces among those activities will require highly diverse workplaces.

In the developed countries, the shift from manufacturing to service and information economies will require that the sales force be as diverse as the populations of customers (Jackson & Alvarez, 1992).

This chapter examines the issues that will be faced by the managers of tomorrow in these diverse workplaces. It begins with definitions of the meaning of culture, race, ethnicity, and nationality. It examines the changes in the workplace that diversity requires. Then it explores basic issues such as whether the melting pot or multiculturalism are desirable or possible directions of social change, and the ways in which multiculturalism can be accommodated. Next it presents a theoretical model that should prove helpful in keeping in mind, at one time, the major relationships among the key variables that define diversity and its consequences.

Definitions

Culture is to society what memory is to individuals (Kluckhohn, 1954). In short, it consists of ways of perceiving, thinking, and deciding that have worked in the past and have become institutionalized in standard operating procedures, customs, scripts, and unstated assumptions that guide behavior.

Culture consists of both objective elements (tools, roads) and subjective elements (concepts, beliefs, attitudes, norms, roles, and values) (Triandis, 1972). A culture must have been adaptive and functional at some point in the history of a group of people who spoke the same language so they could develop shared beliefs, attitudes, norms, roles, and values, and it got transmitted from one generation to the next. Members of a culture must have had a common language so as to communicate the ideas that were later shared, and must have lived during the same time period in areas that were geographically close enough to make communication possible. Thus language, time, and place are three criteria that can be used to identify a culture.

According to this analysis, there are about 10,000 cultures in the world (it is estimated that there are about 6,170 distinct languages; Moynihan, 1993, p. 72). Because there are fewer than 200 members of the United Nations, it means that most nations are multicultural.

There are many factors, in addition to language, that help communication. Living in the same neighborhood, being members of the same physical type (colloquially called a race), having same occupation, same descent from particular ancestors (ethnicity), same gender, age, and so on provide opportunities to develop similar subjective cultures, reflected in similar attitudes and the like. A major dimension of cultural variation is between collectivist and individualist cultures. This dimension has received prominent treatment in studies of culture and work (Erez & Earley, 1993; Triandis, Dunnette, & Hough, 1994).

Ideologies About Diversity

Cultures emerge in different ecologies and are shaped in such a way that people can solve successfully the problems of existence (Berry, 1967, 1976). The schedules of reinforcement that people experience in each ecology result in unique ways of perceiving the social environment (Triandis, 1972). These perceptions occur along dimensions that have a neutral point, called the level of adaptation (Helson, 1964). This point shifts according to the experiences that people have in a particular environment. For example, in wealthy countries, the neutral point for financial compensation is much higher than in poor countries. A salary of $16,000 per year seems “low” in the United States, but its equivalent, 500,000 rupees per year, seems “high” in India. In short, the same stimulus has different meanings, depending on whether it falls above or below the level of adaptation, which shifts according to the experience that people have in a particular environment.

Two polar points of view have been proposed to deal with diversity. On the one hand, there is the melting pot conception (Zangwill, 1914), which argues that the best country has a single homogeneous culture. Japan has refused to receive migrants, on the ground that this will reduce the quality of life in that society. On the other hand, there is the multiculturalism conception, which assumes that each cultural group should preserve as much of its original culture as is feasible, without interfering with the smooth functioning of the society. Canada has an official multicultural policy.

The multiculturalism viewpoint requires, ideally, that each individual does develop a good deal of understanding of the point of view of members of the other relevant cultures. One aspect of this understanding is that each person should give approximately the same meaning to observed social behavior that the actor of this behavior gives. For example, in cultures where people are trained to give respect to powerful others by not looking at them in the eye, it is common for people to look down when spoken to by others. Yet in cultures that are more egalitarian, looking away can be attributed to being distracted, disinterested, hostile, or noncooperative. Thus people do not make the same attributions concerning the causes of this behavior. A multicultural person learns to make approximately the same attributions that the actors make in explaining their own social behavior (Triandis, 1975). Thus using multiple cues, such as ethnicity, social class, gender, and so on, the observer may say “perhaps this person is showing respect by looking away.”

Ethnocentrism

Most humans are ethnocentric (i.e., they judge events as good if they are similar to the events that occur in their own culture). That is inevitable, because we all grow up in specific cultures and view those cultures as providing the only “correct” answers to the problems of existence (Triandis, 1994). As we encounter other cultures, we may become less ethnocentric, but it is only if we reject our own culture that we can become nonethnocentric, and that is relatively rare.

Because all humans are ethnocentric, they make “ethnocentric attributions.” For example, when I went to India the first time in 1965, I wrote to a Western hotel and asked for a reservation and got back a card that had two lines: “We have,” and “we do not have a room for the dates you requested.” There was an X next to “we do not have a room.” I made the ethnocentric attribution that an X meant that they did not have a room. The correct attribution, however, as I found out later, was that “they cancel the category that does not apply.” In short, I misunderstood the message, because I assumed that they use X-marks the same way I do.

Myriad examples of this kind can be given. Let me add just two. Many people from collective cultures (Triandis, 1988, 1990) find receiving “personal credit” quite embarrassing, because they believe that the group should receive credit for a job well done. The expression of public appreciation can embarrass many Asians and Native Americans. Of course, from a Western point of view, credit and public appreciation are perceived as very positive events, but that is often an ethnocentric attribution.

Another example concerns treating everyone equally or in a personalized way. Western bureaucratic theory emphasizes treating everyone the same. In short, if you are going to praise Mr. Jones, you must praise Mr. Tanaka, if both did an equally good job. But what if Mr. Tanaka does not want public exposure?

When people from different cultures work together, their ethnocentrism will result in misunderstandings and lower levels of attraction. The greater the distance between two cultures, the lower the rewards experienced from work together. If the behavior of the other people in the workplace does not make sense, because individuals do not make sufficiently similar attributions, one experiences a loss of control. Such loss of control results in depression (Langer, 1983) and culture shock (Oberg, 1954, 1960) and dislike of the other culture’s members.

The more the interactions with these members are intergroup (emphasizing their membership in groups), the more the cultural differences will be emphasized. If they become interpersonal (paying attention only to the personal attributes of the other and ignoring the cultural aspects of the other’s behavior) and the perceiver has had positive experiences with the other person, it is possible to like the member of the other culture in spite of the cultural distance (Tajfel, 1982). However, there are some necessary conditions. Contact has to lead to the perception of similarity. This can be achieved if there is no history of conflict between the two cultures, if the person knows enough about the other culture to anticipate the culturally determined behaviors of the other person, if the person knows the other’s language, and if they have common friends and common goals (Triandis, Kurowski, & Gelfand, 1994).

The Need for a Theoretical Framework

Social psychologists have long examined intergroup relations (e.g., Stephan, 1985). There are numerous studies and theoretical frameworks, but the relationships appear to be operating the way a balloon reacts: If you push in one place, you get a change in many other places. To understand how the variables operate together as a system, we need a theoretical framework that places the main variables in relation to each other. This chapter will describe such a framework, which I hope can be the basis for more systematic research in the future. The framework is conceived as appropriate for the study of intergroup relations in situations where there is considerable “cultural distance” (differences in social class, language, religion, family structure, or political systems).

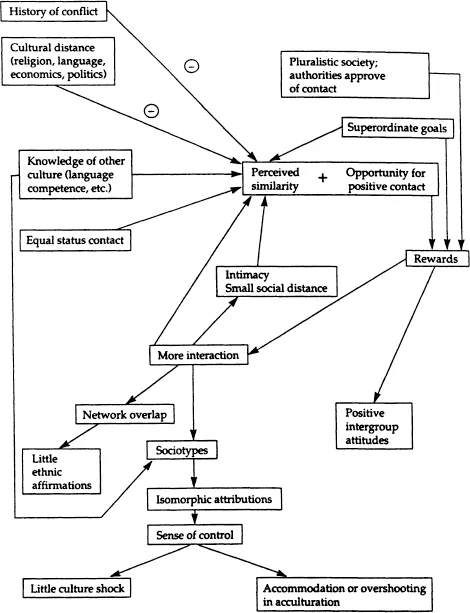

One problem with such a framework is that to make it comprehensive the number of variables that must be included is very large. Of course, the more complex the framework, the more difficult it is to test it. Furthermore, if we include the most important variables, we cannot include the less important even when they are relatively important, to avoid complicating the framework beyond the possibility of testing. Thus I have chosen not to include some variables in the framework itself but to mention them in the discussion of the framework. Similarly, Figure 1.1 does not include all the arrows that are important, but some of the relationships not shown in this figure are discussed in the text.

Tests of this framework are not yet available, but there is a vast literature that is consistent with it. Furthermore, the framework suggests numerous intervention strategies. If such interventions prove successful, the framework will be supported.

Figure 1.1. A Theoretical Model for the Study of Diversity

SOURCE: From Triandis, Kurowski, and Gelfand (1994).

The rest of this chapter first defines and suggests methods for the measurement of the key concepts of the framework. It then presents the framework and suggests how it can be used to test interventions.

Definitions and Measurements

Task Structure

Tasks differ in structure. That is, they vary in the extent that one and only one solution, method of doing them, or approach is optimal (high structure) as opposed to tasks that can be done with many methods, that is, are susceptible to many satisfactory solutions and approaches (low structure). For example, teaching that 2 + 2 = 4 is, by this definition, a high-structure task; exploring the meaning of “virtue,” the way Socrates did in ancient Athens, is a low-structure task.

History of Relationship

Each relationship—such as African Americans versus European Americans, men versus women, bisexuals versus heterosexuals—has its own history. This history structures the meanings that people give to interpersonal contact. When the history has been one of negative interactions (e.g., exploitation), people tend to see the out-group as the “enemy” and to be predisposed toward negative stereotyping, attitudes, and behaviors. Authoritarian personalities are especially likely to see the in-group as “totally in the right” and the out-group as “totally in the wrong,” in such confrontations.

Cultural Distance

Cultures are similar or different (distant) to the extent that they include many similar or different elements. Such elements can be objective or subjective. Objective distance depends on the linguistic distance of the two cultures, and the differences in the social structures, religions, and political and economic systems in use. Subjective distance depends on the dissimilarity of the subjective cultures of the two groups.

Linguists have identified language families, revealing why it is very easy to learn French if one already knows Italian, but more difficult to learn English, and even more difficult to learn Hindi. But all those languages belong to the Indo-European language family, and all the speakers of thes...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- An Introduction to Diversity in Organizations

- PART I. Individual Reactions to Diversity

- PART II: Diversity Effects on Groups and Teams

- PART III: Organizational Perspectives on Diversity

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- About the Contributors