![]()

CHAPTER 1

All Those Years Ago

The Historical Underpinnings of Shared Leadership

Craig L. Pearce

Jay A. Conger

The purpose of this book is to articulate a model of a particular form of leadership—shared leadership—and to stimulate future research on this poorly understood form of leadership. We define shared leadership as a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both. This influence process often involves peer, or lateral, influence and at other times involves upward or downward hierarchical influence. The key distinction between shared leadership and traditional models of leadership is that the influence process involves more than just downward influence on subordinates by an appointed or elected leader (see Pearce & Sims, 2000, 2002). Rather, leadership is broadly distributed among a set of individuals instead of centralized in hands of a single individual who acts in the role of a superior.

This conceptualization of leadership stands in stark contrast to traditional notions. Historically, leadership has been conceived around a single individual—the leader—and the relationship of that individual to subordinates or followers (see Chapter 1, Conger & Kanungo, 1998). This relationship between the leader and the led has been a vertical one of top-down influence. As a result, the leadership field has focused its attention on the behaviors, mind-sets, and actions of “the leader” in a team or organization. This paradigm has been the dominant one in the leadership field for many decades. In recent years, however, a few scholars have challenged this conception, arguing that leadership is an activity that can be shared or distributed among members of a group or organization. For example, depending on the demands of the moment, individuals who are not formally appointed as leaders can rise to the occasion to exhibit leadership and then step back at other times to allow others to lead. This line of thinking is gaining attention among leadership scholars. Yet our understanding of the dynamics and opportunities for shared leadership remains quite primitive. At the same time, there is a sense of urgency to understand the dynamics of this phenomenon given growing demands for shared leadership within the world of organizations.

These demands have largely to do with shifts in how work is performed. For example, today the fastest growing organizational unit is the team and, specifically, cross-functional teams. What distinguishes these units from traditional organizational forms is the absence of hierarchical authority. Although a cross-functional team may have a formally appointed leader, this individual is more commonly treated as a peer. For example, outside the team, they often do not possess line authority over the individual members. Moreover, the formal leader is usually at a knowledge disadvantage. After all, the purpose of the cross-functional team is to bring a very diverse set of functional backgrounds together. The formal leader’s expertise represents only one of the numerous functional specialties at the table. The leader is therefore highly dependent on the expertise of team members. Leadership in these settings is not determined by positions of authority or depth of expertise but rather by an individual’s capacity to influence peers and by the leadership needs of the team in a given moment. In addition, each member of the team brings unique perspectives, knowledge, and capabilities to the team. At various junctures in the team’s life, there are moments when these differing backgrounds and characteristics provide a platform for leadership to be distributed across the team.

In addition to organizational demands for team-based work arrangements, there is a parallel demand for leadership to be more equally distributed up and down the hierarchy. This need is being driven by a number of forces. The first is the realization that seniormost leaders may not possess sufficient and relevant information to make highly effective decisions in a fast-changing and complex world. In reality, managers down the line may be more highly informed and in a far better position to provide leadership. Second, speed of response is an organizational imperative given a faster-paced environment. Many companies, for example, have actually incorporated speed as one of their core values (General Electric being the most commonly cited example). This demand suggests that organizations cannot wait for leadership decisions to be pushed up to the top for action. Instead, leadership has to be distributed or shared across the organization to ensure speedier response times. The final force driving the need for shared leadership has to do with the complexity of the job held by the seniormost leader in an organization—the chief executive officer. Increasingly, this individual is hard-pressed to possess all the leadership skills and knowledge necessary to guide complex organizations in a dynamic and global marketplace. In response to this dilemma, there have been a growing number of experiments in which leadership is being shared at the very top. At Dell, for example, there is an office of the CEO where the responsibilities of the chief executive are distributed among several executives. In summary, a powerful set of forces within organizations is fostering greater demand for shared leadership across all levels.

Although the need and appreciation for shared leadership has been growing, our understanding of it lags seriously behind. In large part, this shortcoming is due to the leadership field’s singular focus on the conception of an individual leader to the neglect of distributed forms of leadership. As a result, there have only been a small number of published studies examining shared forms of leadership. For example, until very recently, only two publications have indicated a clear interest in shared leadership as a potential mechanism for constructively engaging in integrated human effort. The first was in the 1920s, and the second occurred more than 40 years later in the mid-1960s. Shortly, we will describe in some detail these two instances.

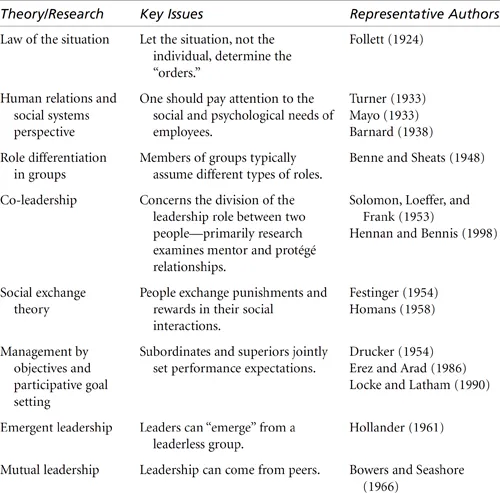

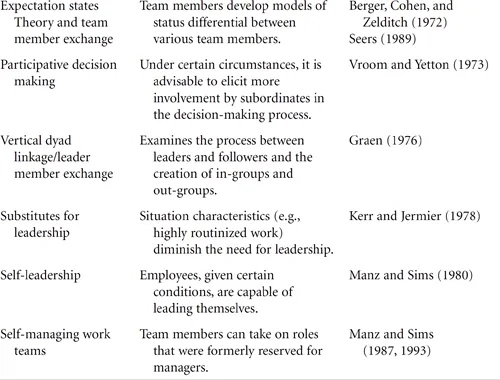

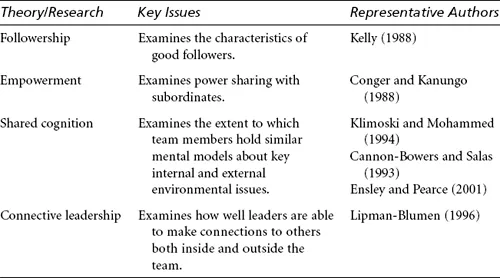

The purpose of this introductory chapter is to provide a historical backdrop for shared leadership. As Bass and Avolio (1993) have astutely noted, the field of leadership often reinvents itself without regard to previous theory. We hope to avoid falling into this selective memory trap and, rather, hope to illuminate the extensive historical underpinnings of the concept of shared leadership. Specifically, we wish to illustrate how our current conceptions of the phenomenon have been shaped by other contributions in the fields of leadership, organizational behavior, psychology, and teamwork (see Table 1.1). In so doing, we intend to craft the proper space for future research on the topic to be well-grounded and to advance the understanding and practice of teamwork and leadership in a deeper, more meaningful way.

The Emergence of the Scientific Study of Leadership: The Leader in a Command Role

Not until the Industrial Revolution was the task of leadership formally studied and documented in a scientific manner: At the beginning of the 1800s, leadership and management was formally recognized as a factor of production when Jean Baptiste Say (1803/1964), a French economist, claimed that entrepreneurs “must possess the art of superintendence and administration” (p. 330). Prior to this time, economists were primarily occupied with two factors of production—land and labor—and, to a lesser extent, capital. During the Industrial Revolution, however, the concept of leadership as important to economic endeavor was recognized. Nonetheless, the predominant role of leadership was command and control. It was not until much later that we observed slight acknowledgment of concepts related to the notion of shared leadership.

The emphasis on leadership centered on control or oversight—in other words, the “vertical model” of leading. For example, James Montgomery (1840) is credited as the first author to scientifically study industrial management and leadership. In 1840, he published a book that compared and contrasted cotton manufacturing in the United States and Great Britain. He concluded that the British organizations were more effective based on their enhanced level of managerial expertise. This expertise was largely focused on the establishment of control systems (Wren, 1994).

Throughout the 1800s, the literature on management focused primarily on organizational forms, structures, and manufacturing processes shaped in large part by the advent of the Industrial Age and the needs of an emerging new industry—the railroads. The advent of the railroads, the first of the large-scale American corporations, necessitated more systematic organizational and leadership approaches to coordinate and control these vast organizations that were geographically dispersed, capital intensive, and employing large numbers of people (Chandler, 1965). One of the early management thinkers in this arena was Daniel C. McCallum. He developed six principles of management, and this was perhaps the first articulation of management principles that could apply across industrial lines. One of McCallum’s principles dealt specifically with the notion of leadership. Although this principle did not indicate what was appropriate leadership, it indicated that the organization should not interfere with supervisors’ “influence with their subordinates” (Wren, 1994, p. 77). Thus, during the mid-1800s, we observe the beginnings of interest in the scientific study of leadership.

Table 1.1 Historical Bases of Shared Leadership

By the turn of the century, thinking on management and leadership had crystallized into what was ultimately termed “scientific management” (Gantt, 1916; Gilbreth, 1912; Gilbreth & Gilbreth, 1917; Taylor, 1903, 1911). The fundamental principle of scientific management was that all work could be studied scientifically and optimal procedures could be developed to ensure maximum productivity. An important component of scientific management was the separation of managerial and worker responsibilities, with managerial ranks having responsibility for identifying precise work procedures and workers following the dictates of management to the letter. Thus, scientific management perhaps went the furthest in clearly articulating a command-and-control perspective on the role of leaders in organizational life. The formally appointed leader was to oversee and direct those below. Subordinates were to follow instructions to the letter. The notion that leaders and their subordinates might mutually influence one another was largely unthinkable at the time.

During the period of the development of scientific management in the United States, two Europeans also made particularly noteworthy intellectual contributions to the formal study of leadership. Henri Fayol from France derived 14 flexible principles of management (Fayol, 1916/1949). Thus, one could credit him with early developments in contingency theory. The second, Max Weber from Germany, developed both a theory of organizational structure—bureaucracy (Weber, 1924/1947)—and a theory of authority or leadership (Weber, 1905/1958). Both individuals clearly articulated influence or leadership processes centered on an individual leader whose authority was top-down and based on command and control. Thus, by the end of the Industrial Revolution, management and leadership had come to be scientifically studied. The consensus was one that emphasized a distinction between leaders and followers and rested on the principle of the unity of command. Orders should come from above and be followed by those below. In addition, these early thinkers on management also spent considerable time trying to figure out ways to prevent followers from shirking responsibilities and thus designed more and more elaborate methods for controlling the behavior of followers. The absolute control of worker behavior—down to the smallest detail—was defined as the prerogative of management.

The Management Field’s Brief Flirtations With Concepts Related to Shared Leadership

Despite this strong historical emphasis on a command-and-control approach to leadership, alternative perspectives did appear in the 20th century—albeit briefly. In fact, in two instances, management thinkers pointed to the possibility of shared leadership processes augmenting the strictly command and control orientation to leadership. These are reviewed below.

Flirtation Number One

Mary Parker Follett (1924) introduced the concept of the law of the situation. The law of the situation stated that rather than simply following the lead of the person with the formal authority in a situation, one should follow the lead of the person with the most knowledge regarding the situation at hand. Thus, Follett proposed a radically different leadership process in contrast to her contemporaries—one closely aligned with the concept of shared leadership.

Follett was a popular speaker and management consultant during the 1920s and was regarded as “the brightest star in the management firmament” of the times (Drucker, 1995, p. 2). Many of her ideas, however, were discounted and discarded by business leaders due to the socioeconomic realities of the late 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. This period erased any notion that workers might actively shape the thinking and actions of management. Peter Drucker recalls a conversation he had with a member of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in the late 1940s that powerfully illustrates the attitudes of the times. Drucker (1995) explains that

when I said something about both management and workers having “a common interest in the survival and prosperity of the company” (also one of Follett’s arguments, although I did not know that at the time), my friend cut me short: “Any company that asserts such a common interest,” he said, “is prima facie in violation of the law and guilty of a grossly unfair labor practice.” (p. 5)

Thus, the common wisdom following the stock market crash and depression years was very much one of command and control: Leaders and subordinates in the modern industrial complex were to have separate roles and conflicting goals. Influence was to remain vertical and unidirectional—downward.

Flirtation Number Two

The second instance of historical interest in shared leadership-type concepts came with the Bowers and Seashore (1966) study of insurance offices. Interestingly enough, Bowers and Seashore did not cite Follett in their theoretical development of a concept they termed “mutual leadership.”

What Bowers and Seashore (1966) empirically documented was that leadership influence processe...