Purpose: This chapter defines community, civic engagement, and social capital, and their relationship to community organizing. Various approaches to community organizing, including consensus organizing, are discussed and compared.

Learning Objectives

- To define and discuss community, civic engagement and social capital and their relationship to community organizing.

- To define and analyze traditional and current approaches to community organizing.

- To define and analyze the consensus organizing approach to community organizing and compare it with traditional and current approaches.

- To analyze and compare various approaches to community organizing by applying them to specific circumstances and issues.

Keywords

- community,

- civic engagement,

- social capital,

- community organizing,

- power-based organizing,

- community building,

- locality development/civic organizing,

- social planning,

- women-centered/feminist organizing,

- consensus organizing

Community, Civic Engagement, and Social Capital

The word “community” can mean different things to different people. Community can be used to refer to communities of association (e.g., religious communities), gender, race, or geography. Cohen (1985) defines community as a system of norms, values, and moral codes that provide a sense of identity for members. Fellin (2001) describes a community as a group of people who form a social unit based on common location (e.g., city or neighborhood), interest and identification (e.g., ethnicity, culture, social class, occupation, or age) or some combination of these characteristics. In many community organizing approaches, geography is the determining factor for community, including “… people who live within a geographically defined area and who have social and psychological ties with each other and with the place where they live” (Mattessich, Monsey, & Roy, 1997, p. 6). This workbook uses a definition of community that emphasizes geography, including neighborhoods, and relationships, including social and psychological connections and networks.

Scholars as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville (Stone & Mennell, 1980) have emphasized the engagement of the community as a focal point of a healthy democracy. More recently, scholars and researchers have argued that civic engagement and participation are decreasing, jeopardizing our democratic system. Etzioni (1993) warned that declining civic engagement and responsibility were eroding the fabric of American society. Putnam's (2000) Bowling Alone provided statistical evidence of the decline in citizen participation over the past 50 years and its negative implications for democratic life. However, Smock (2004) argues that a “significant portion of our nation's population has always been excluded from meaningful participation in the democratic arena” (p. 5). Furthermore, genuine political equality must be built on equal access to voting, as well as direct participation in public decision making.

Putnam's (2000) solution to the erosion of civic engagement involves rebuilding the social fabric or social capital of communities. Social capital is defined as “… the connections among individuals—social networks and norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” (p. 19). Putnam argues that social capital is important for government effectiveness, economic health, and community well-being. Social capital and networks also allow ordinary people to engage in the political process, work together to solve common problems, improve the quality of life, and take advantage of opportunities (Smock, 2004). Furthermore, the role of social capital in understanding and strengthening community organizing and development has been noted by several scholars (Gittell & Vidal, 1998; Hornburg & Lang, 1998; Keyes, Schwartz, Vidal, & Bratt, 1996), including understanding how community organizing facilitates social capital, developing supportive social networks for the production of affordable housing, and building connections that low-income communities may need in the face of diminishing federal responsibility. Temkin and Rohe (1998) found that social capital is a key factor determining neighborhood stability over time, including the overall sense of attachment and loyalty among residents, and the capacity of residents to leverage their relationships and networks into effective community action.

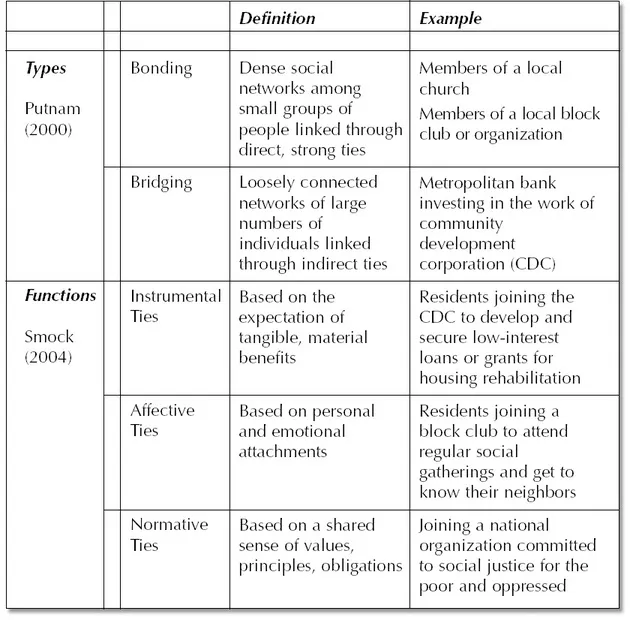

Table 1.1 summarizes the types and functions of social capital. Putnam makes an important distinction between two types of social capital: bonding and bridging (Putnam, 2000). Bonding social capital involves dense social networks among small groups of people that bring them closer together. It is inward-looking, tends to reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups, and accumulates in the daily lives of families and people living in communities through the course of informal interactions. Bridging social capital is composed of loosely connected networks of large numbers of individuals typically linked through indirect ties. It is outward-looking, connects communities and people to others, and encompasses people across diverse social groups and/or localities. Temkin and Rohe (1998) also found that both bonding and bridging social capital are needed to create positive community change.

Smock (2004) further distinguishes social capital and networks by their substance and function, including instrumental, affective, and normative ties. Instrumental ties are based on the expectation of tangible, material benefits; affective ties are based on personal and emotional attachments; and normative ties are based on a shared sense of values, principles, and/or obligations. Community organizing approaches differ in how they facilitate social capital and networks, the forms they take, and the functions they serve. However, they share the same goal: to develop social capital and networks in an attempt to address the erosion of civic engagement, particularly among those typically left out of the decision-making process. Community organizing provides a mechanism for ordinary citizens to impact public decision making in order to improve their social and economic conditions.

Community Organizing Approaches

Table 1.2 summarizes the major approaches to community organizing, including consensus organizing, by synthesizing approaches defined by Rothman (1968, 1996, 2001) and Smock (2004). Approaches and models of community organizing have evolved over the last century; however, initial approaches can be traced back to Saul Alinsky (1946, 1971), who is seen as the founder of community organizing. His approach to community organizing, called conflict organizing, was the dominant form of community organizing practiced over the past century and it continues to be practiced today (Eichler, 2007; Smock, 2004). Saul Alinsky (1971) incorporated the idea of self-interest as a motivating factor for community involvement. The goal of conflict organizing was empowerment through the development of People's Organizations in which regular people with similar self-interests would come together and confront and make demands on the power structure to create improvements for the community (Eichler, 2007; Smock, 2004).

Social Action

Today's social action models have their roots in conflict organizing. Social action approaches assume the existence of an aggrieved or disadvantaged segment of the population that needs to be organized to make demands on the larger community for increased resources or equal treatment (Rothman, 1995). The goals of social action include making fundamental changes in the community, such as redistributing resources and gaining access to decision making for marginal groups, and changing legislative mandates, policies, and practices of institutions.

Smock (2004) distinguishes between power-based and transformative social action models (see Table 1.2). Power-based organizers believe there is a power imbalance and they must work to shift or build power. However, transformative models believe that the power structure/system is fundamentally flawed, and they work to radically restructure it. Power-based models emphasize bridging social capital based on instrumental ties and individual self-interest. Transformative models facilitate social capital based on normative ties that is bonding (e.g., among small groups of residents) and bridging (e.g., with groups of activists and organizations outside their neighborhood based on a shared ideological vision).

Examples of national organizations using social action approaches today include the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), which was created by Saul Alinsky; ACORN (Association of Communities Organizations for Reform Now); and the Midwest Academy. Smock provides examples of organizations that utilize power-based (e.g., West Ridge Organization of Neighbors in Chicago) and transformative organizing approaches (e.g., Justice Action Group). While social action is the p...