This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Domicile and Diaspora investigates geographies of home and identity for Anglo-Indian women in the 50 years before and after Indian independence in 1947.

- The first book to study the Anglo-Indian community past and present, in India, Britain and Australia.

- The first book by a geographer to focus on a community of mixed descent.

- Investigates geographies of home and identity for Anglo-Indian women in the 50 years before and after Indian independence in 1947.

- Draws on interviews and focus groups with over 150 Anglo-Indians, as well as archival research.

- Makes a distinctive contribution to debates about home, identity, hybridity, migration and diaspora.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Domicile and Diaspora by Alison Blunt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Domicile and Diaspora: An Introduction

The photograph on the cover of this book was taken in February 1948, six months after Indian Independence and the Partition of India and Pakistan. It was taken outside a bungalow in a railway colony near Chittagong in what was then East Pakistan and is now Bangladesh (see Figure 1.1). It is a photograph of an Anglo-Indian girl, Felicity, with her ayah’s daughter, 1 both dressed up in saris made from a pair of old curtains, and it was taken by Felicity’s father, who worked on the railways. In many ways, this photograph could be viewed as a classic representation of British domesticity in India, forming part of a long tradition of British families posing with their servants and reproducing an empire within as well as beyond the home. 2 But this photograph differs in three main ways. First, it was taken after Independence, when many of the British elite had left India. For those who remained, either waiting for a passage home or, in fewer cases, ‘staying on’, 3 family photographs could now less easily represent imperial domesticity and an empire within the home. Second, although the Bengali girl looks far less confident than two-year-old Felicity, they appear more similar than different in other ways. The Bengali girl is standing further back, with her hand to her face, and returns a far less assured gaze to her mother’s employer. But both girls are dressed up in the same way, both are holding dolls, and both have been playing together. Finally, unlike photographs of British domesticity in India, Felicity is an Anglo-Indian rather than a British girl.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the term ‘Anglo-Indian’ referred to the British in India, and is still sometimes used in this way. 4 But since the Indian Census of 1911, the term has referred to a domiciled community of mixed descent, who were formerly known as Eurasian, country-born or half-caste. Anglo-Indians form one of the largest and oldest communities of mixed descent in the world, and continue to live in India as well as across a wider diaspora, particularly in Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Descended from the children of European men and Indian women, usually born in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, 5 Anglo-Indians are English-speaking, Christian and culturally more European than Indian. Before Independence in 1947, the spatial politics of home for Anglo-Indians were shaped by imaginative geographies of both Europe (particularly Britain) and India as home. Although Anglo-Indians were ‘country-born’ and domiciled in India, many imagined Britain as home and identified with British life even as they were largely excluded from it. In many ways, Anglo-Indians imagined themselves as part of an imperial diaspora in British India. Indian nationalism and policies of Indianization gave a new political urgency to AngloIndian ideas about home and identity. Some Anglo-Indians who did not feel at home in India settled in a homeland called McCluskieganj, whereas many more migrated after Independence. In 1947, there were roughly 300,000 Anglo-Indians in India and, against the advice of Anglo-Indian leaders, at least 50,000 had migrated by 1970, half of whom resettled in Britain in the late 1940s and 1950s. 6 The second main wave of migration was to Australia in the late 1960s and 1970s once White Australia migration policies had become less restrictive.

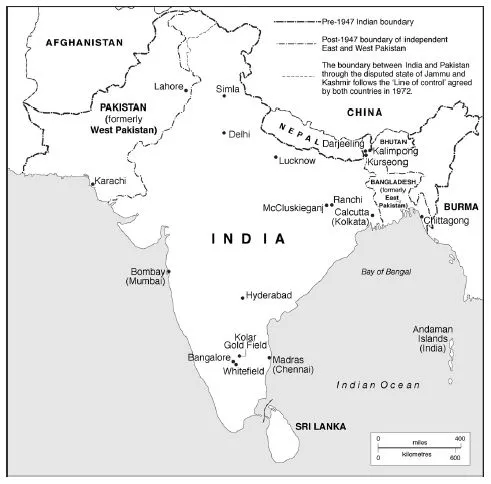

Figure 1.1 Map of the Indian subcontinent

In the 1935 Government of India Act, Anglo-Indians were defined in relation to Europeans in terms of their paternal ancestry and domicile:

An Anglo-Indian is a person whose father or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent but who is a native of India. A European is a person whose father or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent and who is not a native of India. 7

Whereas Anglo-Indians and Europeans shared European paternal descent, Anglo-Indians were born in India and would, before Independence, and unlike most Europeans, expect to die there. Although written out of this definition, the maternal line of descent for Anglo-Indians usually included an Indian woman, often as far back as the eighteenth century. This gendered and geographical definition of what it meant to be an Anglo-Indian formed the basis for the definition that has been part of the Indian Constitution since 1950. 8 Since 2002, the date that the legal definition was adopted in 1935 has been designated ‘World Anglo-Indian Day’, which is celebrated by community functions held in India and across the wider diaspora.

The legal definition is important in personal as well as official terms as it informs how many Anglo-Indians understand and explain their identity and community. For example, a teacher who grew up in Lahore before Independence and now lives in Lucknow told me about her family background by explaining the origins of the Anglo-Indian community:

I shall start from approximately three hundred years ago. The British came out to India and stayed there. Now some of them married. Well, there’s no such thing as an Anglo-Indian that they married, they actually married the Indian girls. So the British and that Indian lady started up a line of AngloIndians. By the time my grandfathers came out, which was two hundred years after that, one came with the Welsh regiment and one came with the Irish regiment . . . there was a line of Anglo-Indian ladies. . . . They married a mixture of Anglo-Indians. Therefore we Anglo-Indians are a different strata. . . . I think I have two-thirds British blood in me, and one-third Indian, hence the way I dress, the way I speak, the way I live.

In 1951, three years after the photograph on the cover was taken, Felicity moved to Britain with her parents and older sister, Grace. Felicity lost both her knowledge of Hindi and her Anglo-Indian accent, and grew up as her family’s ‘foreign child’. This description comes from a 2001 album entitled Panchpuran by the folk-singer Bill Jones, who is Felicity’s daughter Belinda. The album includes the same photograph of Felicity and her friend on the inside cover. The word panchpuran is Hindi for five spices and, according to Belinda, describes not only her music but also her family. As she says, ‘my mum’s family are Anglo-Indian and came to England in 1951, and my dad was born and bred in Wolverhampton in the West Midlands’. In the title track, the word ‘is used to mean many different things all mixed together’. The a capella song describes, through her Aunty Grace’s eyes, ‘the trials of adjusting to life in a country which is not your homeland’. 9

This book is about the spatial politics of home for Anglo-Indian women like Felicity and Grace, both in India and across a wider diaspora. I explore the intersections of home and identity for Anglo-Indians in the fifty years before and after Independence, both domiciled in India and resident in Britain and Australia. I consider the ways in which Anglo-Indian women have felt both at home and not at home in India, Britain and Australia, and the ways in which they have embodied and domesticated personal and collective memories and identities of mixed descent. I also investigate the ways in which such memories and identities have been politically mobilized and resisted through depictions of Anglo-Indian women and through the imaginative and material spaces of home.

Domicile and Diaspora considers the spatial politics of home in relation to imperialism, nationalism, decolonization and multiculturalism, and seeks to extend feminist and postcolonial ideas about mobile and located homes and identities in relation to critical ‘mixed race’ studies. This book is part of a wider attempt not only to explore material and imaginative homes as key locations for theorizing identity, but also to write the home and domesticity into grand narratives of modernity, imperialism and nationalism. 10 Moving beyond binaries such as public and private space and imaginative geographies of ‘self’ and ‘other’, I investigate the power-laden interplay of home and identity in terms of spatial politics. This term refers to home as a contested site shaped by different axes of power and over a range of scales. Mobilizing identity beyond an individual sense of self, and geographies of home within, but also beyond, the household, I focus on their collective and political inscription over space and time and on their contested embodiment by women.

To do so, I explore the spatial politics of home on three intersecting scales. On a household scale I discuss social reproduction, material culture, domesticity and everyday life, particularly focusing on the ways in which Anglo-Indian domesticity has been influenced by both European and Indian ideas of home. I also explore the ways in which an identification with Britain and/or India as home was reproduced on a domestic scale, and the roles of Anglo-Indian women, particularly as wives and mothers, in fashioning a distinctively Anglo-Indian domesticity. On a national scale, I am interested in the intersections between home, identity and nationality and the ways in which Anglo-Indians identified with Britain and/or India as home both before and after Independence and how this was embodied by women and both domesticated and resisted within the home. I also explore the political mobilization of Britain as fatherland and India as motherland, ideas about Anglo-Indians as a homeless community within the country of their birth, and the foundation and promotion of homelands for AngloIndian colonization and settlement. Finally, on a diasporic scale I chart transnational geographies of home and identity for Anglo-Indians in Britain and Australia, reflecting the two main waves of migration by Anglo-Indians after Independence. I explore the implications not only of Independence but also the 1948 British Nationality Act and the White Australia Policy on Anglo-Indian migration, and the ways in which an Anglo-Indian identity has become more visible in the context of official multiculturalism.

Domicile

The term ‘domicile’ invokes geographies of home, settlement and residence, and is both conceptually and empirically significant for this book. One of the main arguments of this book concerns the critical connections between home and identity, whereby a sense of self, place and belonging are shaped, articulated and contested through geographies of home on scales from the domestic to the diasporic. But, more than this, the term ‘domicile’ is particularly apt for studying Anglo-Indians, who formed a large part of the ‘domiciled community’ in India. Unlike the ‘heavenborn’ British elite, who usually returned home on their retirement, the ‘country-born’ domiciled community consisted of people of European descent who were permanent residents in India. 11

The home has begun to attract an increasing amount of critical attention across the humanities and social sciences. 12 As a space of belonging and alienation, intimacy and violence, desire and fear, the home is charged with meanings, emotions, experiences and relationships that lie at the heart of human life. Studies of home as a space of lived experience and imagination range from a focus on everyday life and social relations to domestic form and design, and material, visual and literary cultures of home. Moving beyond the separation between public and private spheres, current studies of home often investigate mobile geographies of dwelling, the political significance of domesticity, intimacy and privacy, and the ways in which ideas and lived experiences of home invoke a sense of place, belonging or alienation that is intimately tied to a sense of self. Such geographies of home traverse scales from the domestic to the global, mobilizing the home far beyond a fixed, bounded and confining location. Studies of home on a domestic scale include work on housing, household structure, domestic divisions of labour, paid domestic work, material cultures of home and homelessness. On a national scale, ideas about home have been studied in relation to debates about citizenship, nationalist politics, indigeneity and multiculturalism. Beyond national borders, research on diasporic, transnational and global geographies includes studies of different domestic forms, multiple places of belonging, cultural geographies of home and memory, and global patterns of domestic labour. A key feature of research on home has been the ways in which it is not only located within but also travels across these different scales, 13 as shown by research on the political significance of domesticity in anti-colonial nationalism, 14 the bungalow and the highrise as transnational domestic forms, 15 and the transnational employment of domestic workers. 16 Domicile and Diaspora explores how the spatial politics of home are mobilized on different, coexisting scales and over material and imaginative terrains.

Another key theme within recent research on home is an interest in the critical connections between home and identity, whereby ideas of home invoke a sense of place and displacement, belonging and alienation, inclusion and exclusion, that is not only intimately tied to a sense of self but also reflects the importance of intimacy. 17 An interest in home and identity within geography can be traced back to the work of a number of humanistic geographers writing in the 1970s and 1980s who celebrated the home as a site of authentic meaning, value and experience, imbued with nostalgic memories and the love of a particular place. 18 But, as Gillian Rose argues, humanistic geographers largely failed to analyse the home as a gendered space shaped by different and unequal relations of power, and as a place that might be dangerous, violent, alienating and unhappy rather than loving and secure. 19

More recent research has addressed the spatial politics of home and identity in more critical and contextual ways, redressing not only the ‘suppression of home’, but also apolitical celebrations of home. In metaphorical terms, images of home form part of a wider spatial lexicon that has become important in theorizing identity, and are often closely tied to ideas about the politics of location and an attempt to situate both knowledge and identity. 20 Through life stories and through archival, textual and ethnographic research, feminist and postcolonial critiques have been particularly important in tracing and traversing the metaphorical and material meanings of home. Feminist postcolonial work has investigated the contested sites of home and domesticity as critically important not only in the social reproduction of nation and empire, but also in revealing the interplay of power relations that both underpinned and undermined such processes of social reproduction. Important themes within this work include the domestication of imperial subjects, particularly as servants, housewives, mothers and children; the material cultures of domesticity, both in the metropolis and in the wider empire; and the home as a site of inclusion, exclusion and contestation, both at times of conflict and in the more everyday practice of imperial rule.21 Other research has explored the importance of the home and domesticity in shaping anti-imperial nationalist politics, particularly through the roles of women both within and beyond the home. 22 Such studies challenge the masculinist knowledge that either ignores the home completely or overlooks the power relations that exist within it. Alongside the work of many black feminists who have rewritten home as a site of creativity, subjectivity and resistance, 23 such studies also challenge a white, liberal feminism that has understood the home primarily as a site of oppression for women. Rather than see home as a solely gendered space, usually embodied by women, such writings also reveal domestic inclusions, exclusions and inequalities in terms of class, age, sexuality and ‘race’. 24

Ideas about home and identity are a recurrent theme in work on, and by, people of mixed descent. Alongside a wide literature on ‘interracial’ partnering, parenting, fostering and adoption, 25 there is a growing literature on home and identity that extends beyond domestic life and family relationships to explore a wider sense of place and belonging. According to Joanne Arnott, ‘possibly the most difficult issue for people of mixed heritage is that of belonging’: 26 of finding a place to call home. In a book entitled Scattered Belongings, Jayne Ifekwunigwe writes that ‘In the de/territorialized places, which ‘‘mixed race’’ cartographers map, the idea of ‘‘home’’ has, by definition, multilayered, multitextual and contradictory meanings.’ 27 Such complex and multiple mappings of home often reveal a sense of identity and belonging as simultaneously personal and transnational, as shown by feminist autobiographical writings on the plural concurrence of homes and identities. For example, Velina Hasu Houston writes that ‘As an Amerasian who is native Japanese, Blackfoot Indian, and African American, I am without the luxury of state (‘‘home’’). . . . Home is sanctuary from the world, but it is not found in one physical place or in a particular community.’ 28 In recent years, particularly in the United States, many people have claimed and asserted their place within a wide and diverse community of mixed ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One: Domicile and Diaspora: An Introduction

- Chapter Two: At Home in British India: Imperial Domesticity and National Identity

- Chapter Three: Home, Community and Nation: Domesticating Identity and Embodying Modernity

- Chapter Four: Colonization and Settlement: Anglo-Indian Homelands

- Chapter Five: Independence and Decolonization: Anglo-Indian Resettlement in Britain

- Chapter Six: Mixed Descent, Migration and Multiculturalism: Anglo-Indians in Australia since 1947

- Chapter Seven: At Home in Independent India: Post-Imperial Domesticity and National Identity

- Chapter Eight: Domicile and Diaspora: Conclusions

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index