- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Combining the main findings, methods and analytic techniques of this central approach to language and social interaction, along with real-life examples and step-by-step explanations, Conversation Analysis is the ideal student guide to the field.

- Introduces the main findings, methods and analytic techniques of conversation analysis (CA) – a growing interdisciplinary field exploring language and social interaction

- Provides an engaging historical overview of the field, along with detailed coverage of the key findings in each area of CA and a guide to current research

- Examines the way talk is composed, and how conversation structures highlight aspects of human behavior

- Focuses on the most important domains of organization in conversation, including turn-taking, action sequencing, repair, stories, openings and closings, and the effect of context

- Includes real-life examples and step-by-step explanations, making it an ideal guide for students navigating this growing field

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Talk

Talk is at the heart of human social life. It is through talk that we engage with one another in a distinctively human way and, in doing so, create what Erving Goffman (1957) once described as a “communion of reciprocally sustained involvement.” We use talk to argue, to complain, to woo, to plead, to commemorate, to denigrate, to justify, to entertain and so on. Clearly, if we didn’t talk we would not have the lives we do.

This book offers an introduction to “conversation analysis” (CA): an approach within the social sciences that aims to describe, analyze and understand talk as a basic and constitutive feature of human social life. CA is a well-developed tradition with a distinctive set of methods and analytic procedures as well as a large body of established findings. In this book I aim to introduce this tradition by guiding readers through a series of topics including turn-taking, action formation, sequence organization and so on. In this introductory chapter I attempt to give some of the flavor of the approach by examining a few fragments of conversation, sketching out in broad brush strokes some basic ways in which they are organized. My goal is essentially twofold. First, and most importantly, I hope to convey at least some of the immediacy of conversation analysis – the fact that what is most important for conversation analysis is not the theories it produces or even the methods it employs but rather the work of grappling with some small bit of the world in order to get an analytic handle on how it works. Secondly, I want to make a point about the way that conversational practices fit together in highly intricate ways. In the interests of clarity I have divided this book into chapters each of which focuses on some particular domain of conversational organization. In point of fact, of course, these different domains of organization are fundamentally interconnected. This interconnectedness creates something of a problem for a book like this one. It means that if we start off talking about the way turns at talk are distributed we soon find it necessary to make reference to the ways in which troubles can be fixed and this then requires some discussion of the way sequences of actions hang together. As Schegloff (2005: 472) suggests, it seems as though one can’t do anything unless one knows everything! Where then to begin? We have to start somewhere and since the book in its entirety is an attempt to come to terms with the interconnectedness of practices in talk-in-interaction, here I just want to jump into the water. My aim for now, then, is simply to show that, in conversation as in talk-in-interaction more generally, one thing truly is connected to a bunch of other things.

Intersecting Machineries

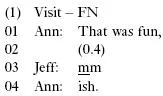

And so, to that end, here is a bit of conversation. To understand it, you’ll need to know that Ann and her husband Jeff had been entertaining two old friends and their young child. The friends had stayed overnight, for breakfast and into the early afternoon. After some rather extended goodbyes, the couple left and Ann and Jeff came back into the house. The following exchange then occurred:

This short fragment may seem at first glance unremarkable but, as I hope to show in the following pages, it illustrates many important features of conversation. It also exemplifies the principle of interconnectedness that I’ve already alluded to. Another way to put it is to say that, if we take any bit of talk, such as that presented in the example above, we find that it is the product of several “organizations” which operate concurrently and intersect in the utterance, thereby giving it a highly specific, indeed unique, character. At this point, a term like “organizations” may seem a bit obscure, but what I mean is actually pretty straightforward. Basically there is an organized set of practices involved in first getting and, secondly, constructing a turn, another such organized set of practices involved in producing a sequence of actions, another set of practices involved in the initiation and execution of repair and so on. Harvey Sacks who, along with Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson, invented the approach to social interaction now called “conversation analysis”, sometimes used the metaphor of machines or machinery to describe this.

In a way, our aim is . . . to get into a position to transform, in what I figure is almost a literal, physical sense, our view of what happened here as some interaction that could be treated as the thing we’re studying, to interactions being spewed out by machinery, the machinery being what we’re trying to find; where, in order to find it we’ve got to get a whole bunch of its products. (Sacks 1995, v. 2:169)

The machinery metaphor is quite revealing. What we get from it is a picture of speakers and hearers more or less totally caught up in and by the socially organized activities in which they are engaged. This is a highly decentralized or distributed view of human action that places the emphasis not on the internal cognitive representations of individuals or on their “external” attributes (doctor, woman, etc.) but on the structures of activity within which they are embedded.

It will be useful to keep this metaphor of machineries in mind as we move into the analyses of this chapter. Our inclination as ordinary members of society and as language users is to think of talk in a much more individualistic, indeed, atomistic way. Here’s a fairly pervasive view of the way that talk works: The words that I produce express thoughts which exist inside my mind or brain. These thoughts-put-into-words are sent, via speech, to a hearer who uses the words to reconstruct the original thoughts. Those thoughts or ideas are thus transferred, by means of language, from a speaker to a hearer. Although this is not the place to discuss this commonplace view of language and communication I mention it here so as to draw a contrast with the view Sacks proposes when he speaks of “machineries”.1

If we think about this little fragment in these terms, that is, as the product of multiple, simultaneously operative and relevant organizations of practice, or “machineries” for short, we can get a lot of analytic leverage on what may at first seem somewhat opaque.

Let’s start by noting that there is an organization relating to occasions or encounters taken as wholes. For a given occasion, there are specific places within it at which point particular actions are relevantly done. An obvious example is that greetings are properly done at the beginning of an encounter rather than at its conclusion. Similarly, introductions between participants who do not know one another are relevant at the outset of an exchange. If I meet a friend on the street and do not fairly immediately introduce her to the person with whom I’m walking, I may well apologize for this – saying something like “Oh, I’m so sorry this is Jeff” – where the apology is specifically responsive to the fact that the introduction has not been done earlier. When an action is done outside of its proper place in conversation it is typically marked as such (with “misplacement markers” like “by the way . . .” and so on). Now I think most people will agree that one of the things people regularly do when their guests leave is to discuss “how it went”. Notice then that Ann’s utterance can be heard as initiating just such a discussion. It does this by making a first move in such a discussion, specifically by positively evaluating or assessing the event. Of course, an utterance like this not only assesses (or evaluates) what has just taken place; it also, in doing so, marks its completion. This utterance does that in part by explicitly characterizing the event as past with “was”. So, to begin with, we can see this utterance as coming in a particular place within the overall structural organization of an occasion – at its completion.

Let’s now consider this fragment in terms of turns-at-talk. This first thing to notice is that there is something about “That was fun” that makes it recognizable as a possibly complete turn, whereas the same is not true for “that was”, or “that”, or “that was fu” etc. In English, turns can be constructed out of a sharply restricted set of grammatically defined units – words, phrases, clauses and sentences. In the example we are looking at the turn is composed of just one such “sentential” unit (even with “ish” added) but in other examples we will see turns composed of multiple units. In characterizing the turn as “possibly” complete we are not hedging our bets but rather attempting to describe the talk from the point of view of the participants. Jeff may anticipate that the turn will end with “fun” but he can’t be sure that it will; as it turns out this is both a possible completion and the actual completion of the turn, but as we’ll see it’s quite possible to have a possible completion which is not the actual completion (indeed, the addition of “-ish” here extends the turn, retrospectively casting the turn as not complete at the end of “fun”).

Now, the possible completion of a turn makes transition to a next speaker relevant in a way it is not during the course of that unit’s production. So we call such places “transition relevance places” and we’ll see, in chapter 3, that speaker transition is organized by reference to such places. The point is, of course, that when Ann finishes her utterance – “That was fun” – she may relevantly expect Jeff to say something by virtue of the way turn-taking in conversation is organized. So we have two more organizations – the organized sets of practices involved in both the construction and the distribution of turns – implicated in the production of this fragment of conversation.

We noticed that the completion of “That was fun” is a place for Jeff to speak. If he had spoken there what might he have said? Although the range of things that Jeff could have said is surely infinite, some things are obviously more relevant and hence more likely than others. One obvious possibility is “yeah, it was” or just “yeah”. Either such utterance would be a “response” to “That was fun” and would show itself to be a response by virtue of its composition. A response like this would then give us a paired set of actions – two utterances tied together in an essential way as first action and its response. In chapter 4 we will see that actions are typically organized into sequences of action and that the most basic such sequence is one composed of just two utterances – a first pair part and a second pair part – which form together an “adjacency pair”. The utterances which compose an adjacency pair are organized by a relation of “conditional relevance” such that the occurrence of a first member of the pair makes the second relevant, so that if it is not produced it may be found, by the participants, to be missing (where any number of things did not happen but were nevertheless not “missing” in the same way).

“Yeah, it was” is more than just a response; it is a specific kind of response: an agreement. We will see that responses to assessments and other sequence-initiating actions (what we will call “first pair parts” like questions, requests, invitations and so on) can be divided into preferred and dispreferred types. We must postpone a detailed discussion of this issue until later (chapter 5). For now I will simply assert that, after an assessment such as “that was fun,” agreement is the preferred response. Any other kind of response in this context may be understood, by the participants, not just for what it is but for what it is not, that is, as something specifically alternative to agreement with the initial assessment. Where agreement is relevant, a kind of “with me or against me” principle operates such that anything other than agreement is tantamount to disagreement. We will see that even delay in responding to an assessment like “That was fun” can suggest that what is being withheld – what is not being said – is disagreement.

In fact, this example provides some evidence for that claim. So here, when Ann’s assessment meets first with delay and subsequently with “mm”, Ann is prompted to modify her original assessment to make it easier for Jeff to agree with if, indeed, he did not agree with its original formulation. So the organization of assessment sequences and the general patterns of preference can tip Ann off here. From Jeff’s delay in responding and from the character of the response he eventually does produce, Ann can infer that he does not agree with her original assessment. She can then modify it in such a way that disagreement is avoided. So we have two more organizations implicated in this fragment of talk – the organization of actions (like assessments and agreements) into sequences and the general patterns of preference (here for agreement).

Ann has produced an utterance, and brought it to completion. Jeff’s response is delayed and when it is eventually produced it is noncommittal: does Jeff agree or not with the assessment “That was fun”? At this point Ann does not produce an entirely new utterance; rather she modifies what she has already said. As noted already, this appears to be prompted by a lack of appropriate uptake by Jeff. We can see this addition of “-ish” to Ann’s utterance as a form of self-repair. With this she not only modifies what she has said, she responds to problems with her original utterance which Jeff’s delay in responding implies. As we will see in chapter 7, there is a preference in conversation for troubles, problems of speaking, errors and so on to be fixed or remedied by the speaker of the trouble rather some other participant. In this example we see that, though Jeff does not fully agree with the assessment “fun” and might perhaps be more willing to describe the visit as “fun-ish”, he does not correct Ann. Rather, he delays his response, and in this way allows Ann a chance to repair, modify or correct her own talk. There is another way in which repair is involved here. One of the things a turn’s recipient can always do at the possible completion of some bit of talk addressed to them is to initiate repair with something like “what?” or “it was what?” or “that was what?” or, again, “that was fun?” or “that was fun?” etc. Because this is an ever-present possibility, the fact that it is not done can be taken to imply that the talk was understood. So by the fact that Jeff does not initiate repair of Ann’s turn, Ann may infer that Jeff (believes he) understood what she has said and that a lack of understanding therefore does not explain his delay in responding. So we have another organization of practices – the organization of repair – implicated in this short fragment of conversation.

Although there is much more we could say about this fragment the larger point should by now be clear: Any utterance can be seen as the unique product of a number of intersecting machineries or organizations of practice. This is an alternative then to the common-sense, “individualist” view, that sees the utterance as the product of a single, isolated individual speaker. It is also an alternative to the “externalist” view which sees the utterance as the product of intersecting, external forces such as the speaker’s (or the recipient’s) gender, ethnic background, age, class or whatever else.

So far we have seen that this exchange involves practices for taking and constructing turns, building sequences of actions, repairing troubles and for speaking in ways fitted to the occasion. There is one more organization of practices that should be mentioned here – those involved in selecting the particular words used to construct the turn. Now you might think that people don’t select words at all; they just use the words that are appropriate for what they are talking about – they simply “call a spade a spade”. The problem with this view is that for anything that one talks about, multiple ways are available to describe or refer to it. We can ask, for instance, why Ann says “that” in “that was fun” instead of “Having Evan, Jenny and Reg” or “The last twenty-four hours” or whatever else. This brings us to a central principle of conversation which Sacks and his colleagues termed “recipient design”: “the multitude of respects in which the talk by a party in a conversation is constructed or designed in ways which display an orientation and sensitivity to the particular other(s) who are the co-participants” (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson 1974: 727). This is an obvious yet absolutely crucial point, that speakers design their talk in such a way as to make it appropriate and relevant for the persons they are addressing. Recipient design encompasses a vast range of phenomena – everything from the banal fact that a speaker will increase the volume of her talk to address a recipient at the back of the room to the subtle nuances of word selection which reflect what the speaker assumes the recipient knows. So with an expression like “that” in “that was fun” the speaker clearly presumes that the recipient will know what she means to refer to in using it. If Ann had said this to someone who phoned after her guests had left, that person might respond with “what was fun?” since they would have no idea what “that” was meant to refer to. This allows us to see the way “that” in “That was fun” was specifically selected for Jeff.

Think also about the way you would refer to the same person in talking to different recipients. With one recipient that person is “Dee”, with another “your Mom”, with another “Ms Greene” and with another “Nana” and so on. Why? Apparently, we select the name by which we presume our recipient knows the person to whom we want to refer. The name we use then is specifically designed for the particular recipient – it is recipient-designed.

I have concluded the discussion of the talk between Jeff and Ann with a consideration of recipient design for a reason. When we talk of “machineries” of turn-taking, of action sequencing or of repair it’s easy to get the sense of these abstract “organizations” operating independently of the real persons engaged in talking to one another. And, of course, there’s a sense in which that’s absolutely correct. Indeed, that is, surely, just the point that Sacks wanted to drive home with the metaphor of “machinery”. However, a focus on these context-free organizations or systems, these intersecting machineries, obviously does not tell the whole story since, as Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) note, whatever happens in conversation happens at some particular time, in some particular place, with some particular group of persons, after some particular thing has just taken place. In short, anything that happens in conversation happens within some particular, ultimately unique, context. As it turns out, although the structures that organize conversation are context-free in certain basic and crucial respects, they are at the same time capable of extraordinary context-sensitivity. We’ve had a glimpse at this in our consideration of recipient design here – enough, I hope, to suggest that CA involves tacking back and forth between the general and context-free on the one hand and the particular and context-sensitive on the other.

Historical Origins of Conversation Analysis

CA emerged in the 1960s through the collaboration of Harvey Sacks, Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. Although CA can be seen as a fresh start within the social and human sciences, it drew inspiration from two important sociologists, Erving Goffman and Harold Garfinkel.2 Goffman’s highly original and innovative move was to direct sociological attention to “situations” – the ordinary and extraordinary ways in which people interact with one another in the course of everyday life. Through a series of analyses Goffman attempted to show that these situations, and especially what he would describe as focused encounters, could be studied as in some ways orderly systems of self-sustaining activity. In a card game, for example, each participant pays attention so that she knows whose turn it is, what has been played, what point the players have reached in the hand and in the game and so on. If one of the players becomes distracted and misses a turn or delays in taking it, others may complain that she is not paying attention, so there are built-in mechanisms for addressing problems that arise as the activity is taking place. Of course, what applies to a card-game applies equally well to conversation:

We must see . . . that a conversation has a life of its own and makes demands on its own behalf. It is a little social system with its own boundary-maintaining tendencies; it is a little patch of commitment and loyalty with its own heroes and its own villains. (Goffman 1957: 47)

Goffman insisted that the organization of human interaction, what he would come to call the “interaction order” (1983), constituted its own social institution. Moreover, according to Goffman, face-to-face, co-present interaction is the basis for all other social institutions that sociologists and others study. Hospitals, asylums, courts of law, households and so on can be seen as environments for various forms of social interaction. What is particularly remarkable about Goffman is that at the time he was writing virtually no one in sociology or anthropology paid any attention to social interaction. A few psychologists, particularly those associated with Roger G. Barker (e.g. Barker & Wright 1951, Barker 1963), whom, by the way, Sacks had read, had begun to treat the “stream of behavior” as a topic of analysis. A number of linguists (e.g. Pittenger 1960, McQuown 1971) had also advocated a study of language as it was actually spoken. And there were murmurs within Anthropology too from people such as Gregory Bateson (e.g. Bateson & Mead 1942, Bateson 1956, 1972), who was interested in gesture and the body as well as the differences and similarities between animal and human communication. But many of these approaches were reductive in the sense that the authors were concerned to show how talk – or speech,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- ffirs

- Title

- copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Transcription Conventions

- 1: Talk

- 2: Methods

- 3: Turn-Taking

- 4: Action and Understanding

- 5: Preference

- 6: Sequence

- 7: Repair

- 8: Turn Construction

- 9: Stories

- 10: Openings and Closings

- 11: Topic

- 12: Context

- 13: Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Conversation Analysis by Jack Sidnell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.