- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy Activities

About this book

At last, a book about the little pieces of occupation which make up life' s real situations and experiences and form a basis for therapy. Offered in the form of stories about practice previously published in the popular US publication Advance for Occupational Therapy Practitioners, this enjoyable book presents occupational therapists as "masters of the mundane." Therapists, students and educators will find this easy to read text a useful tool in guiding clinical approaches to therapy.

Accompanied by theoretical papers by Dr. Estelle Breines and colleagues previously published in refereed international journals, these stories will aid the reader in understanding principles of active occupation that guide practice and shed light on how these ideas can be applied to the education of therapists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

This book is divided into ten chapters which cover a series of topics of interest to occupational therapists. The articles were written, however, in a random order and the organization was undertaken much later. The disorganized approach to the writing is reflective of a problem the profession has in explaining itself as we move back and forth, to and from reductionistic and holistic conceptualizations. These articles were written in an attempt to simplify some complex notions that arose from a study of the underlying philosophical principles that influenced the development of the profession, in order to make them more palatable for readers who would rather focus on less abstract thoughts.

I write with an American bias that I request the reader to forgive. Aside from the fact that the articles originally were written by an American for an American audience, my bias comes from my belief that our profession was instigated by strong influences from the mental hygiene movement which in turn was influenced by the American pragmatists John Dewey, William James, Charles Peirce and George Herbert Mead. In turn, their ideas were driven by the relational notions of Hegel in conjunction with the evolutionary precepts of Charles Darwin.

The pragmatists adopted the notions of time, development and evolution as concepts of change evident in human behavior and experience. They departed from a prevailing notion of truth as absolute, affirming the relevance of objectivity and subjectivity in understanding human endeavor. Each of these scholars applied these ideas to their own specialized areas of study. Peirce’s notions, the most abstract, were applied by James to the study of psychology, by Mead to the study of sociology and by Dewey to the study of education, in which he advanced the notion of learning by doing.

These ideas were promulgated widely at the University of Chicago and elsewhere in the United States and influenced members of the Illinois and National Mental Hygiene Societies, whose names may be familiar to readers. Among these persons of prominence were Adolf Meyer, Eleanor Clarke Slagle, Rabbi Emil Gustave Hirsch, Julia Lathrop and Jane Addams, all foundational figures for American occupational therapy. Hirsch and Lathrop founded the Chicago School for Civics and Philanthropy, the first occupational therapy school, at Addams’ Hull House where Slagle and Mary Potter Brooks Meyer (Adolf Meyer’s wife) studied occupational therapy. It was here that learning through doing was adopted as the professions foundational belief.

Drawing on evolutionary themes, pragmatism, which is a phenomenological philosophical movement, advanced the concept of adaptation that was also adopted by occupational therapy. The pragmatists focused on the ideas that mind and body are inseparable and that the individual contributes to society, just as society contributes to the individual. Occupational therapy established its belief in bringing people to their highest levels of functioning so they could become contributing members of society. The founders of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy, later the American Occupational Therapy Association, demonstrated the application of these ideas across the various disorders of mind and body.

In time, these abstract ideas were set aside by the occupational therapy profession. Attention was largely focused on the mundane, practical aspects of living as occupational therapists opened the door to the acceptance of common sense as a guide for behavior. Yet, in time, the profession again looked for philosophical explanations for what we inherently know and experience.

In an attempt to meet this need, I, along with others, began to study and analyze our profession’s origins and organizing beliefs. As I studied the ideas of the pragmatists, I tried to formulat e a comprehensive model that featured ideas held by occupational therapists, describing this model as occupational genesis. Occupational genesis describes the interactions among egocentric elements (mind and body), exocentric elements (time and space) and consensual elements (social factors such as relationships, language, roles, regulations), and the changes in these interactions over the course of time. For example, infants move randomly with primitive cognitive abilities (egocentric), surrounded by cribs and mobile toys (exocentric), relating to caretakers in dependent roles (consensual). As development progresses, physical and mental skills develop (egocentric), the toys and environments of childhood (exocentric) alter and relationships with siblings, friends and family grow (consensual). As aging progresses, each of these elements and their interactions change.

This model also applies to the understanding of cultural development.

Drawing from Dewey’s work in the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, we can observe that the knowledge base and skills of individuals and the artifacts of cultures change over time, influencing and being influenced by social relationships and the activities in which one engages.

Human evolution is driven by the relationships among egocentric, exocentric and consensual elements. In each time period and in each geographic environment, humans drew upon their physical and mental capacities, in conjunction with the tangible features of their environments, in collaboration with those in their society. From this idea, the model of occupational technology emerged. Occupational technology is based on the premise that human beings have been technological creatures from the beginning of pre-history to the modern era, in the same way that occupational therapists have been technologists from their inception to today.

Occupational genesis focuses on the relational and developmental nature of humans. Occupational technology focuses on the technological features of that development. Both are derivatives of the pragmatists’ beliefs, organized to create models for occupational therapists to use in clinical practice, education and research.

The reader is urged to read original and interpretive texts to better understand than I can explain what the pragmatists offered. Toward this end, I suggest a list of papers and books to help guide your reading. And in keeping with the ordinary things that ordinary people express themselves through, I offer the simple articles that follow.

Suggested additional readings

Breines EB (1986) Origins and Adaptations: A Philosophy of Practice. Lebanon, NJ: Geri-Rehab.

Breines EB (1992) Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch: ethical philosopher and founding figure of occupational therapy. Israel Journal of Occupational Therapy 1: E1–E10.

Breines EB (1995) Occupational Therapy Activities from Clay to Computers: Theory and Practice. Philadelphia: EA. Davis.

Dewey J (1916) Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. Toronto: Collier Macmillan.

Dewey J (1929) The Quest for Certainty: A Study of the Relation of Knowledge and Action. New York: Minton, Balch & Co.

Mayhew KC, Edwards AC (1936) The Dewey School: the Lab School of the University of Chicago. 1896–1903. New York: Appleton-Century.

Serrett KD (1985) Another look at occupational therapy’s history: paradigm or pair of hands? Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 5(3): 1–31.

Understanding ‘occupation’ as the founders did

Originally published in British journal of Occupational Therapy, Nov. 1995,58(11): 4.58–60

Abstract

The term ‘occupation’ is both ambiguous and encompassing. This term was adopted by the founders of the profession as a means of incorporating a variety of perspectives on the profession. Interrelating concepts deriving from pragmatism and the mental hygiene movement offer a rationale for understanding occupation. Terms used to describe occupation are egocentricity (mind/body elements), exocentricity (time/space elements) and consensuality (social elements). The integration of these aspects in occupation offers an explanation for the holism advanced by the profession at its outset and today.

Introduction

The literature of occupational therapy repeatedly calls for the definition and accurate use of terms. Darnell and Heater (1994) reiterate this call, in this case urging the explicit use of the term ‘occupation’ in lieu of terms such as activity. They ground their argument in Nelson’s (1988) work, which defines occupation as ‘the relationship between occupational form and occupational performance’ (p. 633).

Defining occupation, just like defining occupational therapy, seems to be a process in which occupational therapists repeatedly engage (Christiansen, 1994; Mosey, 1981). Although the Representative Assembly of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) has recently adopted new and comprehensive definitions of various terms essential to the profession, including occupation (Position Paper on Occupation, 1995, unpublished), there is no reason to believe that the last word has been written about this topic of critical concern to the profession. Therefore, new perspectives on this word of such importance to the profession may be useful for helping therapists to explain themselves and their work to patients and colleagues, and may serve as a basis for study and research.

The term occupation has been used to describe various models and concepts. These include occupational behaviour (Reilly, 1974), human occupation (Kielhofner and Burke, 1980), occupational performance (Llorens, 1979; Mosey, 1981), occupational genesis (Breines, 1990), occupational science (Clark et al., 1991) and occupational adaptation (Schkade and Schultz, 1992).

Certainly, the term occupation is used freely to describe various conceptual organizations, and appears to mean many different things. Darnell and Heater (1994) are correct to suggest the clarification of the term occupation, and to invite the expanded use of this term to characterize the profession which carries its name. In response, this article frames the discussion in terms deriving from foundation philosophical and historical sources.

At the outset

This author believes that, at the outset of the profession, the term occupation was deliberately selected because of both its ambiguity and its comprehensiveness. An attempt is made to demonstrate this through extrapolation from historical and philosophical evidence, because one is limited to post hoc interpretation when the original sources neglected to offer explicit answers to questions that emerge long after the witnesses are gone.

At the outset, there was considerable discussion about naming the profession. After numerous suggestions, such as ‘reeducation’ and ‘reconstruction’, were rejected by one or another of the founders in vigorous debate, the term occupational therapy was selected (Barton, c. 1914–17; Dunton, c. 1916–17; Licht, 1967; Slagle, c. 1916–17). Occupation appears to have been a word that the founders could agree upon, possibly because it held various meanings and could serve as a mediating term. To find a common word for a profession that synthesized many views was critical, because the profession was founded by a number of individuals who saw the value of occupation in different arenas of practice. Among these were Barton (1919) in sheltered work and physical rehabilitation; Dunton (1918) and Slagle (1914) in mental health; Kidner (c. 1917) in tuberculosis; and Tracy (1918) in medical illness.

Many of these individuals were influenced by the mental hygiene movement. This movement, which originated in the USA around the turn of the century, was recognized for its efforts in social activism (Cohen, 1983). The mental hygiene movement had many members in common with the Arts and Crafts movement, and had many principles in common. Many of the foundational figures of occupation therapy, including Adolf Meyer and Eleanor Clarke Slagle, were affiliated with the National Mental Hygiene Society or the Illinois Mental Hygiene Society (Breines, 1986a).

The mental hygiene movement was influenced by the philosophy of pragmatism expounded at the University of Chicago. Pragmatism is a phenomenological philosophy which focuses on the relationships among individuals, their artifacts and environments and their societies, as represented by their actions in personal and interpersonal well-being. John Dewey, a principal proponent of pragmatism, is recognized for the concept widely known as ‘learning through doing’.

Both the Chicago School for Civics and Philanthropy, where Slagle studied occupational therapy, and the Henry B Faville School of Occupational Therapy, where she later taught, were located at Hull House in Chicago, where pragmatism was taught by John Dewey and Julia Lathrop (Addams, 1910). The Faville School functioned under the sponsorship of the Illinois Mental Hygiene Society. And it was at the University of Chicago that Adolf Meyer (1950) taught and had collegial relationships with John Dewey and George Herbert Mead, foundational philosophers of pragmatism. Here, social activism and pragmatism were united, and built foundations for occupational therapy (Breines, 1986a; Serrett, 1985a, 1985b).

Pragmatism speaks to the interaction of the mind and body of individuals with their tangible and social environments by means of active occupation (Dewey, 1916; Mead, 1932, 1938). This relational belief system, structured in concepts of time, evolution, history and development, can serve as a model for understanding the term occupation and other terms stemming from the same root.

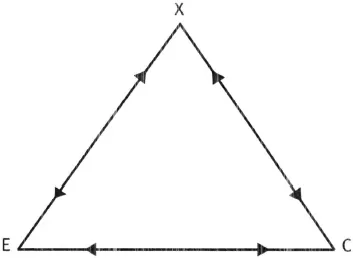

Three distinct concepts

‘Occupation’ can be described according to three distinct but interrelating concepts; egocentric, exocentric and consensual. These three concepts derive from the model of occupational genesis (see Figure 1; Breines, 1990, 1995), and are grounded in pragmatism. Occupational genesis defines egocentric as all aspects of mind and body; exocentric as all aspects of time and space; and consensual as all social phenomena such as roles, rules and language. Consistent with the relational aspects of pragmatism, these three concepts, egocentricity, exocentricity and consensuality, and their components – mind, body, time, space and others such as social influences – are in constant flux and interact throughout life in the performance of life’s tasks.

Figure 1: Egocentric (E), exocentric (X), and consensual (C) elements influence one another. The relationships among these elements are represented by the lines. Occupational therapy changes these relationships by influencing (adapting) any or all of these elements: mind/body, time/space, or social interactions.

Source: Breines (1995). Copyright © 1995, FA Davis.

Three major concepts are revealed when analyzing the term occupation. These concepts are:

1. To be occupied, representing the egocentric aspect. When one is occupied, one is engaged both in mind and in body, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes alternatively. When performing a task, mind and body integrate. When the mind is occupied, the body performs. When the body is occupied, the mind is distracted or engaged. These interactive phenomena are called upon in practice and underlie the concept of goal-directed activity. Occupational therapy is focused primarily on the education of mind and/or body toward health.

2. To occupy, representing the exocentric aspect. When engaged in tasks, one occupies space and occupies time; one is interacting with these elements of the environment, while these elements themselves interact. That is, the individual learns to adapt to the world and/or the environment is adapted to the individual. Both of these perspectives on adaptation are reflected in practice, as in the use of wheel-chairs and splints, and in learning skills used in self-care, work and play. Adaptation, whether spatial or temporal, is a fundamental tool and expectation of practice.

3. Occupation, representing the consensual aspect. This third aspect is often described in terms of vocation or work, but also represents interactive play or other endeavors in which one collaborates, competes or otherwise engages with or for others in socially responsible behaviors. Play-based therapies, activity group process, work hardening, sheltered workshops and homemaking training, all aspects of occupational therapy practice, fall under this rubric.

Addressing the meaning of occupational therapy

These three uses of the term occupation together address the meaning of occupational therapy as suggested by our founders, and as understood today. The human being engages all these elements – mind, body, time, space and others – in performing life’s tasks, and practice considers them all, using each element to affect each other element in the pursuit of health. These fundamental concepts prevail regardless of clinical population, but different areas of practice emphasize different elements. ‘Psych. OTs’ may emphasize the mind while ‘phys.dis. OTs’ may emphasize the body, but both consider each other element as it applies to their patients. All therapists use the physical and social environments to effect change.

The diverse ways in which occupation can be defined suggests that this term is extraordinarily comprehensive. Moreover, precisely because of this comprehensiveness, occupation has evaded unique definition.

The founders’ selection of the term occupation to describe the profession was not incidental. Considerable argument was entered into before the name of our profession was selected (Barton, c. 1914–17; Licht, 1967; Slagle, c. 1916–17). Rather, this author believes that the term ‘occupation’ was ultimately decided upon to mean all of the elements described above, in part and in whole, if not explicitly, then in terms of its compatibility with the various beliefs of the founders. Furthermore, this holistic interpretation may be the reason that the term has been retained as the profession’s identity, despite recurring reports of discomfort with it (Marmer, 1994; ADVANCE Staff, 1994)·

Were the profession to dissociate itself from any of the three elements of occupation cited above, it would no longer be the profession it has aspired to be. In the absence of any one element – mind, body, time, space and others – we could not be who we are, nor practice as we do in the holistic breadth of practice. The term occupation encapsulates all aspects of who we are as a profession because it represent the comprehensiveness that identifies us. What brilliance the founders demonstrated in arriving at this identity for the profession!

Conclusion

This analysis is consistent with the profession’s foundational philosophy, and is consistent with practice in all its elements, at our origin as well as today. This interpretation may help therapists better to comprehend diverse features of their profession that have sometimes appeared to be in conflict, while recognizing the position of these separate elements in regard to the holism of the profession. Furthermore, this analysis, in addition to other descriptions and uses of the term occupation, affirms the comprehensiveness with which this holistic profession and its philosophy hold.

Rabbi Emil Gustave Hirsch: ethical philosopher and founding figure of occupational therapy

Originally published in Israel journal of Occupational Therapy 1992 1(1): E1–E9

Abstract

Rabbi Hirsch is identified in several sources as a founder of the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy, the first school of Occupational Therapy. Hirsch’s relations are traced to the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy and Addams, Julia Lathrop, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, Adolf Meyer, and the Baltimore community. Hirsch’s religious and ethical philosophy are analyzed and correlated with principles of pragmatism and occupational therapy, in which enablement is advanced as being of mutual benefit to the individual and society.

Introduction

Julia Lathrop and Rabbi Hirsch founded the first school of Occupational Therapy at the Chicago School for Civics and Philanthropy. (Dunton, 1915)

This statement was made in 1915 in a book by Dr William Rush Dunton, Jr., one of the founders of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy (NSPOT), the forerunner of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Dunton’s statement is repeated in several secondary sources (Brunyate, 1958; Licht, 1967), but is not elaborated on, and does not reveal Lathrop and Hirsch’s reasons for establishing the school. This brief statement is the only indication that Hirsch was an individual of significance to Occupational Therapy. No other mention of Hirsch appears in Occupational Therapy literature, and no mention of Occupational Therapy appears in Hirsch’s papers.

Historical associations

While there is no direct reference, either in archival material or secondary sources as to Hirsch’s specific purpose with regard to Occupational Therapy, the literature reveals an abundance of sources from which his ideals can be extrapolated, and the case can be made that he held similar beliefs to those of his colleagues and contemporaries.

At the turn of the century, the faculty at the University of Chicago included: John Dewey (1916) and George Herbert Mead (1932), the famous pragmatist philosophers; Hirsch, himself a philosopher, educator and religious leader; Jane Addams (1910), the great social activist of Hull House; Oscar Triggs (1902), a founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Thinking Deep Thoughts

- 3 The Magic of Healing

- 4 Old Crafts – New Ideas

- 5 Toys and Games

- 6 Saving the Environment:

- 7 Home, Garden and Beyond

- 8 Pets and People

- 9 Occupational Technology and Occupational Therapy

- 10 Teaching and Learning through Activity

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Occupational Therapy Activities by Estelle B. Breines in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Occupational Therapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.