- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Tectonics

About this book

The third edition of this widely acclaimed textbook provides a comprehensive introduction to all aspects of global tectonics, and includes major revisions to reflect the most significant recent advances in the field.

- A fully revised third edition of this highly acclaimed text written by eminent authors including one of the pioneers of plate tectonic theory

- Major revisions to this new edition reflect the most significant recent advances in the field, including new and expanded chapters on Precambrian tectonics and the supercontinent cycle and the implications of plate tectonics for environmental change

- Combines a historical approach with process science to provide a careful balance between geological and geophysical material in both continental and oceanic regimes

- Dedicated website available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/kearey/

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Historical perspective

1.1 CONTINENTAL DRIFT

Although the theory of the new global tectonics, or plate tectonics, has largely been developed since 1967, the history of ideas concerning a mobilist view of the Earth extends back considerably longer (Rupke, 1970; Hallam, 1973a; Vine, 1977; Frankel, 1988). Ever since the coastlines of the continents around the Atlantic Ocean were first charted, people have been intrigued by the similarity of the coastlines of the Americas and of Europe and Africa. Possibly the first to note the similarity and suggest an ancient separation was Abraham Ortelius in 1596 (Romm, 1994). In 1620, Francis Bacon, in his Novum Organum, commented on the similar form of the west coasts of Africa and South America: that is, the Atlantic coast of Africa and the Pacific coast of South America. He also noted the similar configurations of the New and Old World, “both of which are broad and extended towards the north, narrow and pointed towards the south.” Perhaps because of these observations, for there appear to be no others, Bacon is often erroneously credited with having been first to notice the similarity or “fit” of the Atlantic coastlines of South America and Africa and even with having suggested that they were once together and had drifted apart. In 1668, François Placet, a French prior, related the separation of the Americas to the Flood of Noah. Noting from the Bible that prior to the flood the Earth was one and undivided, he postulated that the Americas were formed by the conjunction of floating islands or separated from Europe and Africa by the destruction of an intervening landmass, “Atlantis.” One must remember, of course, that during the 17th and 18th centuries geology, like most sciences, was carried out by clerics and theologians who felt that their observations, such as the occurrence of marine fossils and water-lain sediments on high land, were explicable in terms of the Flood and other biblical catastrophes.

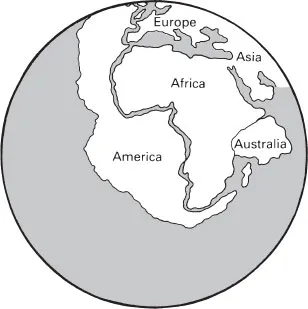

Another person to note the fit of the Atlantic coastlines of South America and Africa and to suggest that they might once have been side by side was Theodor Christoph Lilienthal, Professor of Theology at Königsberg in Germany. In a work dated 1756 he too related their separation to biblical catastrophism, drawing on the text, “in the days of Peleg, the earth was divided.” In papers dated 1801 and 1845, the German explorer Alexander von Humbolt noted the geometric and geologic similarities of the opposing shores of the Atlantic, but he too speculated that the Atlantic was formed by a catastrophic event, this time “a flow of eddying waters … directed first towards the north-east, then towards the north-west, and back again to the north-east … What we call the Atlantic Ocean is nothing else than a valley scooped out by the sea.” In 1858 an American, Antonio Snider, made the same observations but postulated “drift” and related it to “multiple catastrophism” – the Flood being the last major catastrophe. Thus Snider suggested drift sensu stricto, and he even went so far as to suggest a pre-drift reconstruction (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Snider’s reconstruction of the continents (Snider, 1858).

The 19th century saw the gradual replacement of the concept of catastrophism by that of “uniformitarianism” or “actualism” as propounded by the British geologists James Hutton and Charles Lyell. Hutton wrote “No powers are to be employed that are not natural to the globe, no action to be admitted of except those of which we know the principle, and no extraordinary events to be alleged in order to explain a common appearance.” This is usually stated in Archibald Geikie’s paraphrase of Hutton’s words, “the present is the key to the past,” that is, the slow processes going on at and beneath the Earth’s surface today have been going on throughout geologic time and have shaped the surface record. Despite this change in the basis of geologic thought, the proponents of continental drift still resorted to catastrophic events to explain the separation of the continents. Thus, George Darwin in 1879 and Oswald Fisher in 1882 associated drift with the origin of the Moon out of the Pacific. This idea persisted well into the 20th century, and probably accounts in part for the reluctance of most Earth scientists to consider the concept of continental drift seriously during the first half of the 20th century (Rupke, 1970).

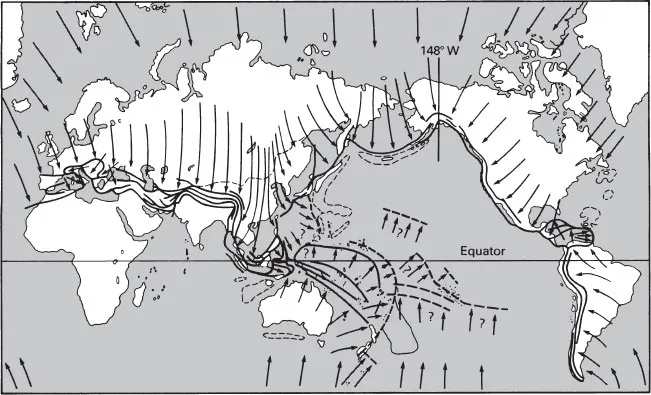

Figure 1.2 Taylor’s mechanism for the formation of Cenozoic mountain belts by continental drift (after Taylor, 1910).

A uniformitarian concept of drift was first suggested by F.B. Taylor, an American physicist, in 1910, and Alfred Wegener, a German meteorologist, in 1912. For the first time it was considered that drift is taking place today and has taken place at least throughout the past 100–200 Ma of Earth history. In this way drift was invoked to account for the geometric and geologic similarities of the trailing edges of the continents around the Atlantic and Indian oceans and the formation of the young fold mountain systems at their leading edges. Taylor, in particular, invoked drift to explain the distribution of the young fold mountain belts and “the origin of the Earth’s plan” (Taylor, 1910) (Fig. 1.2 and Plate 1.1 between pp. 244 and 245).

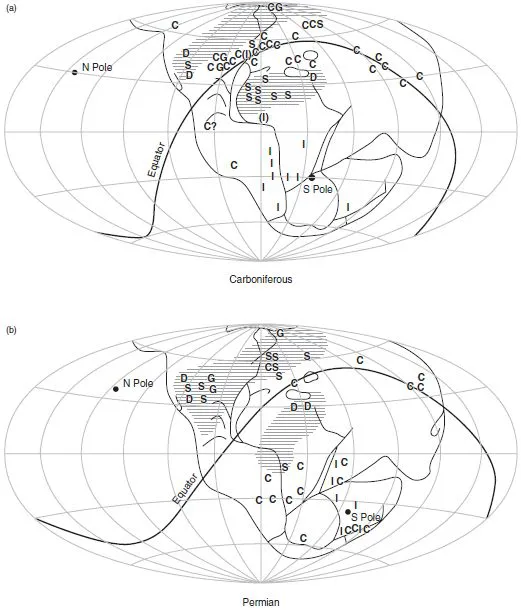

The pioneer of the theory of continental drift is generally recognized as Alfred Wegener, who as well as being a meteorologist was an astronomer, geophysicist, and amateur balloonist (Hallam, 1975), and he devoted much of his life to its development. Wegener detailed much of the older, pre-drift, geologic data and maintained that the continuity of the older structures, formations and fossil faunas and floras across present continental shorelines was more readily understood on a pre-drift reconstruction. Even today, these points are the major features of the geologic record from the continents which favor the hypothesis of continental drift. New information, which Wegener brought to his thesis, was the presence of a widespread glaciation in Permo-Carboniferous times which had affected most of the southern continents while northern Europe and Greenland had experienced tropical conditions. Wegener postulated that at this time the continents were joined into a single landmass, with the present southern continents centered on the pole and the northern continents straddling the equator (Fig. 1.3). Wegener termed this continental assembly Pangea (literally “all the Earth”) although we currently prefer to think in terms of A. du Toit’s idea of it being made up of two supercontinents (du Toit, 1937) (Fig. 11.27). The more northerly of these is termed Laurasia (from a combination of Laurentia, a region of Canada, and Asia), and consisted of North America, Greenland, Europe, and Asia. The southerly supercontinent is termed Gondwana (literally “land of the Gonds” after an ancient tribe of northern India), and consisted of South America, Antarctica, Africa, Madagascar, India, and Australasia. Separating the two supercontinents to the east was a former “Mediterranean” sea termed the paleo-Tethys Ocean (after the Greek goddess of the sea), while surrounding Pangea was the proto-Pacific Ocean or Panthalassa (literally “all-ocean”).

Figure 1.3 Wegener’s reconstruction of the continents (Pangea), with paleoclimatic indicators, and paleopoles and equator for (a) Carboniferous and (b) Permian time. I, ice; C, coal; S, salt; G, gypsum; D, desert sandstone; hatched areas, arid zones (modified from Wegener, 1929, reproduced from Hallam, 1973a, p. 19, by permission of Oxford University Press).

Wegener propounded his new thesis in a book Die Entstehung der Kontinente and Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans), of which four editions appeared in the period 1915–29. Much of the ensuing academic discussion was based on the English translation of the 1922 edition which appeared in 1924, consideration of the earlier work having been delayed by World War I. Many Earth scientists of this time found his new ideas difficult to encompass, as acceptance of his work necessitated a rejection of the existing scientific orthodoxy, which was based on a static Earth model. Wegener based his theory on data drawn from several different disciplines, in many of which he was not an expert. The majority of Earth scientists found fault in detail and so tended to reject his work in toto. Perhaps Wegener did himself a disservice in the eclecticism of his approach. Several of his arguments were incorrect: for example, his estimate of the rate of drift between Europe and Greenland using geodetic techniques was in error by an order of magnitude. Most important, from the point of view of his critics, was the lack of a reasonable mechanism for continental movements. Wegener had suggested that continental drift occurred in response to the centripetal force experienced by the high-standing continents because of the Earth’s rotation. Simple calculations showed the forces exerted by this mechanism to be much too small. Although in the later editions of his book this approach was dropped, the objections of the majority of the scientific community had become established. Du Toit, however, recognized the good geologic arguments for the joining of the southern continents and A. Holmes, in the period 1927–29, developed a new theory of the mechanism of continental movement (Holmes, 1928). He proposed that continents were moved by convection currents powered by the heat of radioactive decay (Fig. 1.4). Although differing considerably from the present concepts of convection and ocean floor creation, Holmes laid the foundation from which modern ideas developed.

Between the World Wars two schools of thought developed – the drifters and the nondrifters, the latter far outnumbering the former. Each ridiculed the other’s ideas. The nondrifters emphasized the lack of a plausible mechanism, as we have already noted, both convection and Earth expansion being considered unlikely. The nondrifters had difficulty in explaining the present separation of faunal provinces, for example, which could be much more readily explained if the continents were formerly together, and their attempts to explain these apparent faunal links or migrations also came in for some ridicule. They had to invoke various improbable means such as island stepping-stones, isthmian links, or rafting. It is interesting to note that at this time many southern hemisphere geologists, such as du Toit, Lester King, and S.W. Carey, were advocates of drift, perhaps because the geologic record from the southern continents and India favors their assembly into a single supercontinent (Gondwana) prior to 200 Ma ago.

Very little was written about continental drift between the initial criticisms of Wegener’s book and about 1960. In the 1950s, employing methodology suggested by P.M.S. Blackett, the paleomagnetic method was developed (Section 3.6), and S.K. Runcorn and his co-workers demonstrated that relative mov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- The geologic timescale and stratigraphic column

- 1 Historical perspective

- 2 The interior of the Earth

- 3 Continental drift

- 4 Sea floor spreading and transform faults

- 5 The framework of plate tectonics

- 6 Ocean ridges

- 7 Continental rifts and rifted margins

- 8 Continental transforms and strike-slip faults

- 9 Subduction zones

- 10 Orogenic belts

- 11 Precambrian tectonics and the supercontinent cycle

- 12 The mechanism of plate tectonics

- 13 Implications of plate tectonics

- Review questions

- References

- Index

- Color plates

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Global Tectonics by Philip Kearey,Keith A. Klepeis,Frederick J. Vine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze fisiche & Geologia e scienze della terra. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.