![]()

Part 1 Didactics

![]()

1 Fundamental Principles of the Comprehensive Approach

The foundation of a comprehensive practice is a four-part comprehensive evaluation. Dentists often say that they will do a comprehensive evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan if the patient is “having a problem” or if it appears to be “a big case.” First, how do you know whether there is a problem unless the complete exam is done? You can base it on the patient report of symptoms, or lack of symptoms, but there can be significant changes or issues with components of the masticatory system without manifestation of symptoms. These symptom-free issues, also known as signs, can have a significant impact on a treatment plan and the stability of the results. Second, how do you know whether it will be a “big case” unless a complete exam is done? Without the exam, the evaluation is usually based just on an obvious deterioration of teeth or missing teeth and the presence of crowns, bridges, or implants—and if these obvious issues are not present, it is deemed not to be a “big case.”

Part of the problem is with the term big case. It is usually synonymous with needing many units of crowns or bridges. An even bigger problem is falsely assuming that a comprehensive case implies a big case. Even a simple restorative case—that is, some simple restorations on just a few teeth, with concurrent occlusal management for predictability of the restorative result and for long-term health of the patient’s temporomandibular joints and neuromuscular system—should be a comprehensive case.

The Case for the Four-Part Comprehensive Evaluation

What is the rationale of a four-part comprehensive evaluation for patients who have healthy teeth and periodontium, are not complaining of pain or dysfunction, and are not in need of any significant restorative dentistry? Simply put, it serves as a baseline for future comparison. We may not see issues that are immediately in need of treatment, but there are often issues that are not ideal but still do not warrant treatment. These are described as observations and not problems. Examples include slight wear, gingival recession, erosion, and abrasion, etc. If we do a complete base-line examination, at some future point we can repeat this examination and compare it to the baseline. If nothing has changed, we can assure the patient. If any of these issues has gotten worse, we now have the baseline to compare to and have a more valid rationale for suggesting treatment. It is easy for the patient to see the progression especially when comparing photographs and diagnostic casts. Our role as dentists is not just to repair what is broken but to prevent future breakdown and maintain optimal health.

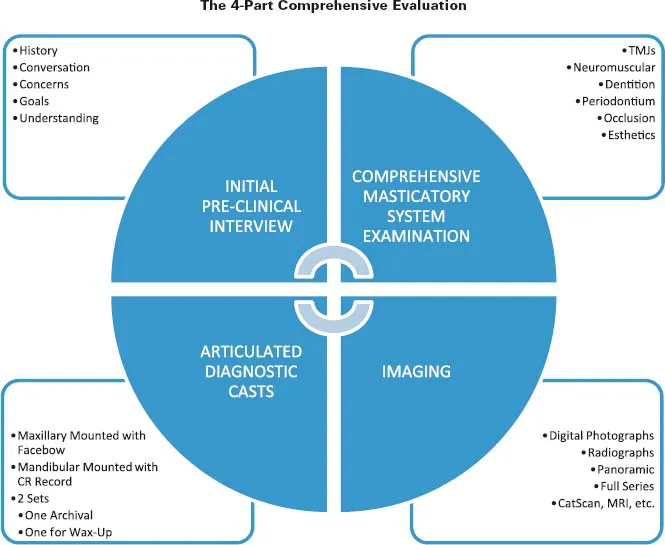

The Details of the Four-Part Comprehensive Evaluation

Figure 1.1 illustrates all the components of the four-part comprehensive evaluation. With the initial interview, clinical examination, necessary imaging, and articulated diagnostic casts completed, we have all the information needed to make a diagnosis and formulate an appropriate treatment plan and treatment sequence. With this complete information about our patients and their masticatory systems, they can “be in our office” even after they have left. Now we can invest some thinking time to sort through all the information. What a valuable service for our patients! This is behind-the-scenes work that we are investing on behalf of our patients. Be sure that you and your team communicate to your patients that you are investing this time on their behalf. If they do not know that you are investing the time, they cannot value and appreciate that effort. Their perception is reality, so be sure that their perception is correct.

The Initial Conversation

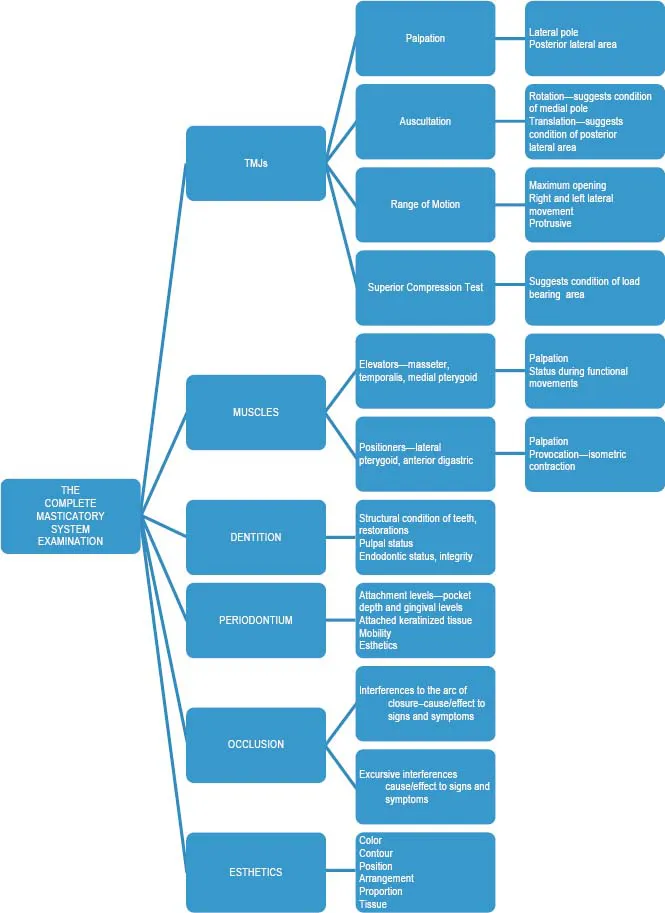

Figure 1.2 illustrates all components of the complete clinical masticatory system examination. After the patient calls the practice, has an initial conversation with the administrative assistant, and is appointed, the process should continue with a one-on-one conversation with the dentist. The purpose of this conversation is for the dentist to get to know the patient, and vice versa, and basically to get the process started on a personal level. The medical and dental history is reviewed and an attempt is made by the dentist to understand the patient’s concerns, desires, and expectations. It is a time for the patient to do most of the talking and for the dentist to do most of the listening. Talking on the part of the dentist should be mainly in the form of questions to help better understand what the patient is trying to convey. Many times, dentists do too much talking during this initial conversation—telling the patient about ourselves, our practices, and the services that we provide for our patients. There certainly is a need to talk about these things, but this initial conversation is not the proper time. As we listen to the patient’s conversation we need to control the urge to offer an answer or a solution; rather we should think of the right question to ask to help us better understand what the patient is trying to tell us. This initial conversation can set the tone for the entire relationship that follows. We want patients to leave this conversation feeling that it is about them and that their best interests are at the top of the list. Once we have listened and truly understand the concerns of the patient, it is a very natural transition to the complete masticatory system examination.

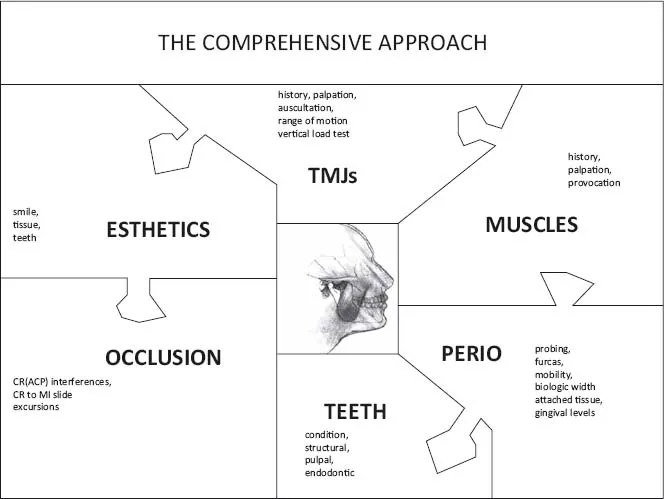

The Clinical System-Based Masticatory System Examination

The second step is a clinical examination of all components of the masticatory system (refer to Figure 1.1). It is important to say that this is a system-based examination and not just a symptom-based examination. It needs to be a systematic, step-by-step evaluation. A lack of symptoms is not a reason to not complete a certain aspect of the clinical evaluation. For example, just because the patient may not complain of temporomandibular joint symptoms does not mean that we should not do a thorough temporomandibular joint examination. There can be significant intracapsular changes with no report of symptoms, and these changes can have significant implications on the long-term stability of our restorative and occlusal results. Knowing and understanding this at the beginning of the case is much better than being unprepared if it becomes an issue after we begin the case. If we know about it ahead of time it’s called a diagnosis. If we find out about it after we began the case because of some issue or problem that arises, we find ourselves making excuses and explanations. An after-the-fact excuse is never going to satisfy the patient. It will always seem to be an oversight on the part of the dentist.

Figure 1.3 illustrates all the parts of a comprehensive clinical masticatory system evaluation. Each part of the examination is like a piece of the puzzle. As we complete all parts of the examination we then have all the pieces of the puzzle to accurately visualize the current status of the patient’s masticatory system. Being thorough and complete with the examination goes a long way to ward eliminating oversights and mistakes in the future.

We need to have a systematic, step-by-step pragmatic approach to the evaluation of all the components of the masticatory system, but we need to be flexible in how we begin and go through the various parts, primarily with the behavioral aspects of a comprehensive evaluation, which are covered in more depth and detail in Chapter 2. Basically we want to use the nformation that we gather during the initial conversation with the patient to guide us through the various parts of the clinical evaluation. For example, if the patient reports a temporomandibular joint problem, the logical place to start is the temporomandibular joint examination. If the patient reports headaches and muscle tension, we consider beginning with the muscle palpation part of the examination. Doing the examination in this way illustrates to patients that we have not forgotten about their chief concerns. You will find patients are more interested and receptive during the examination when it is about them. We don’t want the examination to be something that we do “to” patients but rather something that is done with the active participation of patients.

The Four-Part TMJ Examination

The temporomandibular joint examination consists of four parts: palpation; auscultation; range of motion tests; and superior compression test, also known as a vertical load test. This four-part test, along with any necessary imaging, will suggest to us the condition of the components of the temporomandibular joint.

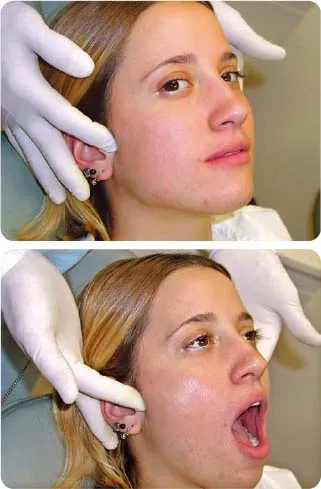

Figure 1.4 illustrates palpation of the temporomandibular joints. With the mandible closed we can palpate the lateral pole and associated structures. With the mandible opened widely and the condyles translated down and forward along the articular eminence, we can palpate the posterior aspects of the temporomandibular joints. Healthy structures should not be uncomfortable or painful to palpation. Gently touch the patient’s shoulder and explain that this represents simply the pressure of the touch. On a scale of 1 to 5, the pressure of the touch is zero. If patient feels more than just a pressure of the touch, ask them to rate the discomfort on a scale of 1 to 5. Tenderness or discomfort to palpation suggests edema or inflammation in those structures. Discomfort to palpation on the lateral pole suggests issues with the lateral aspect of the disc or capsule. Discomfort to palpation of the posterior aspect of the condyles suggests edema or inflammation in the retrodiscal tissues.

Temporomandibular joint issues often have trauma as a contributing factor. It may be microtrauma such as bruxism or macrotrauma such as an accident. Talk to the patient about any past history of trauma, as insignificant as it may seem. A bump to the chin or a sporting accident as a teenager may have been a significant event in the adult patient’s current temporomandibular joint condition.

Figure 1.5 illustrates one aspect of the range of motion tests. Maximum opening and full movement to the left, right, and protrusive are measured. These should be pain-free movements. Ask the patient whether any discomfort is felt during these range-of-motion tests and, if so, to specifically point to the area of discomfort. It may be muscles, joints, or both. This not only gets the patient involved but it also helps you get a sense of condylar movements and muscular coordination. Maximum opening averages 45–55 mm, excursive movements average 9–12 mm. These averages represent approximately a 4:1 ratio between maximum opening and excursions. Deviations from these averages or this ratio might suggest problems with intracapsular structures or muscle coordination. Smaller ranges may not necessarily be a problem; they may be normal for that patient if movement is pain free, if the patient functions well and has no distress, and if those movements are symmetrical and fall within the 4:1 ratio.

Figure 1.6 illustrates auscultation with Doppler ultrasonography. One advantage of the Doppler is that the sound is magnified, which not only helps the dentist in diagnosis but it also helps patients to understand the current condition of their temporomandibular joints. Bear in mind that a meniscus that is normal in condition and position between the condyles and the fossa produces no sound during auscultation. The surface of the normal fibrocartilege disc is smooth, and this already smooth surface is lubricated by synovial fluid. Movement across these surfaces is very quiet. Noises such as crepitation and clicks suggest changes in condition and/or position of the disc, whether or not there is pain. If the disc, either all or part, is displaced anteriorly, the functional surface now becomes the retrodiscal tissues, which are not as smooth a surface and will produce crepitation. This retrodiscal tissue has the capacity to adapt and form a “pseudodisc,” which is a rougher, more fibrotic surface resulting in a higher degree of crepitation. Perforations can occur in this retrodiscal tissue in some patients, resulting in an even coarser crepitation. Functioning bone-to-bone over time can result in a hardening, or ebumation, of those surfaces, resulting in less crepitation. So a careful history is important. The patient may report that they experienced noise for a long time that eventually went away.

The implication of changes in position or condition, even without pain is instability. Instability of joint structures correlates to instability of the occlusion, an issue that both dentists and patients need to be aware of, especially if definitive occlusal and/or reconstructive dentistry is going to be part of the treatment plan.

Bear in mind that the temporomandibular joint is a ginglymo-arthrodial joint, meaning that it both hinges and translates. Structures on the medial aspect of the joint are compressed and under function during hinge rotation; therefore, auscultation during hinge rotation suggests the condition of the structures on the media aspect of the joint. Structures on the superior and lateral aspects of the joint are compressed and under function during transl...