Chapter 1: Understanding Composition

Approaches to Composition

How You See

The Origins of Composition

Understanding Linear Perspective

Composition and Photography

Have you ever studied a snapshot and wondered why it looked amateurish compared to a photograph taken by a more experienced photographer? Even when the subject matter is the same — say, for example, that both photographs depict a shoreline — the difference between them is clear. The master’s image is more captivating, more vital, more powerful than the snapshot. But why? What is it about the more skilled photographer’s image that makes it so compelling? What is it about the skilled photographer’s photograph that promotes it from a snapshot to a work of art?

Many factors can affect a photographic image. Lighting, for one, can greatly influence the outcome of a photographic shoot. So, too, can the camera’s settings — the f-stop, shutter speed, and ISO. The quality of the camera’s lenses can be a factor, as can the use of additional equipment such as a tripod and filters. But more than these is the photo’s composition, that is, the arrangement of the elements within the image. Indeed, composition is the unifying element behind all visual art, from painting to photography and beyond.

Taking a snapshot is a simple matter of picking up a camera and photographing whatever is in front of you. Little, if any, thought process is involved. In contrast, when you compose a photograph, you consciously choose what visual elements to leave in and what to omit from your photos (see 1-1). When a picture is well-composed, the message the image is meant to convey is clearly and effectively communicated, inviting the viewer to appreciate and examine the work.

Approaches to Composition

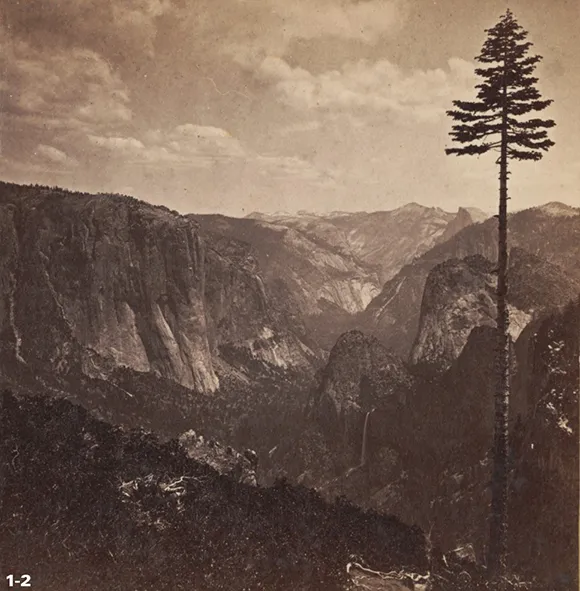

Although it’s true that composition is about choosing which elements your photograph contains, that’s not to say that everyone makes those choices in the same way. Some people carefully position themselves for just the right shot; others painstakingly arrange their subjects, creating their compositions just so. Still others wing it — waiting for the elements of a photograph to naturally coalesce. For example, nineteenth-century photographer Carleton Watkins, famous for his photographs of the American West (particularly Yosemite), didn’t bother setting up his camera until after he had walked around a site, waiting for all the elements in the scene to align in a way that pleased him (see 1-2). Watkins understood how a slight shift in position could change how the components in an image came together, yielding what he called “the best view.”

1-1: Notice how the person leaning against the wall adds scale to the image (105mm, 100 ISO, center-weighted neutral-density filter, f/32.5 at 1/4 second).

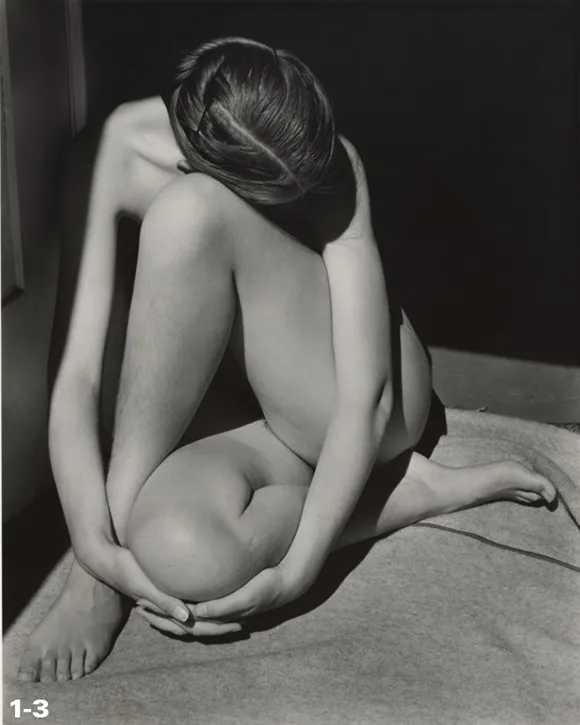

Similarly, Edward Weston, known for his beautiful close-up images of fruits, vegetables, and nudes, carefully arranged his subjects before photographing them, whether they were in the studio or outdoors (see 1-3). In contrast, Henri Cartier-Bresson, renowned for his superb images of people and places (see 1-4), relied more on intuition than planning. He developed a knack for recognizing in a split second, even as the world swirled around him, when a photograph was perfectly composed — what he called “the decisive moment.”

1-2: Best General View, Mariposa Trail, ca. 1860’s. Photograph by Carleton Watkins. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

1-3: Nude, 1936. Photograph by Edward Weston. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents

1-4: FRANCE: The Var department. Hydres. 1932. © Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1932. Magnum Photos

How You See

Why does the way in which a photograph — or other piece of visual art — is composed affect how effectively that piece communicates its meaning? Why do some compositions provoke the viewer to linger on an image, and others barely garner a glance? One answer relates to how you see.

The Physiology of the Eye

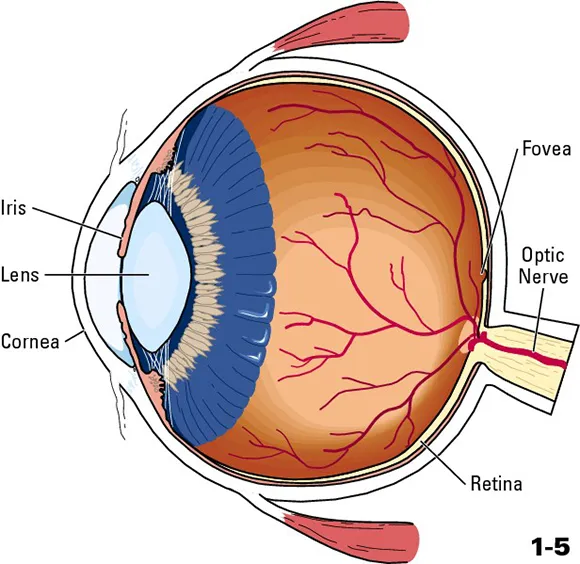

When you perceive something visually, it’s because that object is either emitting or reflecting light, which enters the eye in the form of waves. These waves pass through the eye’s pupil, lens, and cornea to the retina to stimulate visual receptors called rods and cones (see 1-5). Rods enable you to see the general outlines of objects, even in dim light — although without color. In contrast, cones detect color and enable you to discern an object’s details. Cones are concentrated in the fovea centralis — a depressed area in the center of the retina. In contrast, rods are spread around the outer portion of the retina. Rods and cones, when activated by light, transmit nerve impulses to the optic nerve behind the retina, which ushers these impulses to the brain’s visual cortex for processing. To visualize this effect, imagine walking into a dark movie theater when you just came from a brightly lit room. Your eyes can barely make out the seats or what’s in front of you...that is your rods working first, then as more light is gathered, you begin to see more details...that is your cones working.

1-5: An eye in cross-section.

Because humans have two eyes, with pupils roughly 2.5 inches apart, people view the world stereoscopically. That is, each eye sees an object slightly differently. To form a single, 3-D image that conveys depth, dimension, distance, height, and width, the brain merges the image registered by one eye with the image registered by the other. (Note that this applies primarily when the object is fewer than 18 feet away. For objects that are farther out, the brain uses relative size and motion to determine its depth.) The brain also flips the image as in figure 1-6, which is originally upside down due to the way light is refracted through the lenses of the eyes, right side up.

1-6: This is how your brain actually sees the image, upside down, and then flips it right side up (105mm, 50 ISO, f/16 at 1/40 second).

Selective Vision

Although roughly one-third of the brain busies itself with various aspects of seeing, the brain cannot respond to each and every signal sent to it via the optic nerve. The volume of information is simply too great and would quickly overwhelm the brain’s resources. For this reason, your vision is selective. So, rather than processing each bit of data it receives from the optic nerve, the brain processes differences in this data — a slight movement, an alteration in color, a shift in light or shadow. To facilitate this, the eye continually scans the scene before it. Even if your environment is static, you continue to unconsciously scan for changes. The eye also moves to bring different portions of the scene into focus.

Just as you continuously scan your environment, so, too, do your eyes move about when you examine a photograph or other still image. The difference is, a still image is, by definition, static. There are no changes to detect. Even so, as a photographer, you can take advantage of the eye’s impulse to scan by carefully placing the objects in your scene — composing the photograph (see 1-7). When a photograph is well-composed, the eye is naturally drawn to the center of interest, typically comprised of contrasting objects that stand out from their surroundings, before scanning the rest of the photograph (see 1-8).