This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of Modern Psychology in Context

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In A History of Modern Psychology in Context, the authors resist the traditional storylines of great achievements by eminent people, or schools of thought that rise and fall in the wake of scientific progress. Instead, psychology is portrayed as a network of scientific and professional practices embedded in specific contexts. The narrative is informed by three key concepts—indigenization, reflexivity, and social constructionism—and by the fascinating interplay between disciplinary Psychology and everyday psychology.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A History of Modern Psychology in Context by Wade Pickren, Alexandra Rutherford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ORIGINS OF A SCIENCE OF MIND

Since it is the understanding that sets man above the rest of sensible beings, and gives him all the advantage and dominion which he has over them; it is certainly a subject, even for its nobleness, worth our labour to inquire into.John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690

INTRODUCTION

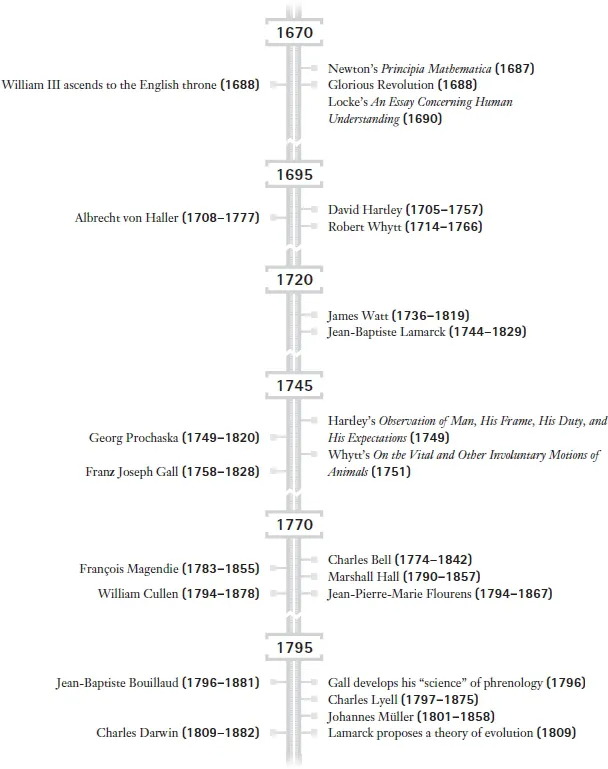

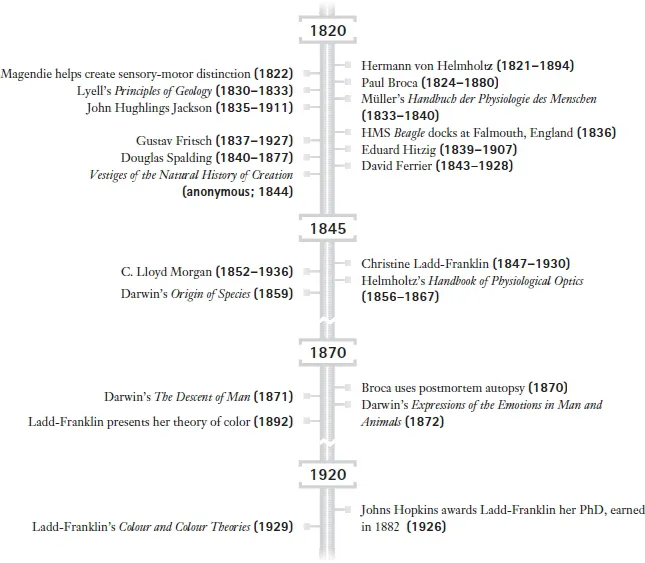

The discipline of Psychology, the history of which we explore in the following pages, did not exist before the mid- to late 19th century. Thus, to begin our history, we have to understand the intellectual and practical developments that made the emergence of such a field possible. As we discuss in this and the next chapter, at least four strands of thought and practice were important for the emergence of Psychology by the end of the 19th century: philosophy, physiology, evolution by natural selection, and creation of a psychological sensibility through everyday practices. Taken together, these four strands made possible both the science and the profession of Psychology, which Graham Richards has termed “big P” Psychology to differentiate the discipline from its subject matter, “little p” psychology (Richards, 2002). The latter includes the everyday psychology that people have used, and continue to use, to make sense of their lives.

The last strand, the creation of a psychological sensibility, is explained and elaborated in the next chapter. In this chapter, we unravel the first three strands by introducing you to basic ideas from the work of philosophers René Descartes and John Locke, the development of an experimental approach to understanding the relation between mind or brain and behavior in 19th-century physiology, and Charles Darwin’s work on evolution and how it included humans within the domain of natural laws.

We take as our point of departure the early modern period, that is, from the 17th century on, as the appropriate time to begin our analyses of the events that made possible the relatively recent emergence of Psychology. In terms of place, we begin with events and people in England and western Europe. This is not to claim that people in no other place or time wrote or thought psychologically about life; as we argue in later chapters, a background of thought relevant to psychology in other cultures came to the fore nearer our own time. Rather, our aim is both pragmatic and historiographical. We are pragmatic because space is limited. Our historiographic rationale is that we think a sound argument can be made that the psychological sensibility characterizing our own time is of relatively recent origin, dating from changes in human experience and human society that were first directly noticeable in the early modern period in England and Europe, and then exacerbated by rapid social changes brought on by such macroscale events as the Industrial Revolution and the spread of Protestant religious beliefs and practices.

Lastly, we think it is useful to consider events and contributions to the development of a psychological sensibility from both elites—that is, those of the upper classes who had access to resources, education, and the power to disseminate their views—and everyday people. It is more usual in a textbook to consider only the contributions of elites, typically philosophers or “men of science”; this chapter focuses on such contributions. The next chapter examines changes in everyday life that many people encountered and incorporated to make meaning in their lives. If, as we suggested in the introduction of this book, Psychology emerged from ways of living, then it follows that we should ask questions about when and how changes in everyday life occurred. While a full set of answers is not possible, since no complete record exists of how people lived and acted in earlier periods, we can provide at least a partial description and analysis based on extant records and writing. While we have an extensive record of philosophical thought from the early modern era, which we draw on in this chapter, in the next chapter we use what is available in the historical record to suggest how nonelites contributed to the emergence of practices that are also part of the lineage that led to the emergence of Psychology.

PHILOSOPHY: DESCARTES AND LOCKE AS EXEMPLARS

The gradual emergence of thought about man in naturalistic terms occurred, paradoxically, in the context of faith, both Protestant and Catholic. Religion and conflicts about correct beliefs and the proper conduct of daily life provided a background for this thinking that held both promise and threat. Nations went to war, and humans lost their livelihoods and often their lives over these matters. Both Descartes and Locke were profoundly affected by this context of religious and political strife, and each attempted to find ways to restore certainty of knowledge and order in civil society. Importantly, their thought also contributed to the eventual emergence of Psychology.

If any one word could characterize the 17th century in England and Europe, it might well be “uncertainty.” The modern nation-state was emerging, and war among nations was endemic. Civil strife that led to civil war in England brought horrors nearly unimaginable that left their marks for generations afterward. The English civil war was directly related to religious beliefs and practices, but religion was also an important factor in changes elsewhere in Europe as the new orientation to personal faith and religious practice introduced by Martin Luther (1483–1546) in the 16th century spread unevenly across the continent. Families, as well as nations, were often divided over questions of faith, whether to follow the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church or one of the new Protestant faiths. When these faiths were linked to the power of the state, many people were persecuted and killed for their beliefs and many fled to other countries. So, on both the national and the personal levels, it was a time of uncertainty as the fabric of life was rewoven in a period of intense social upheaval.

Although no one event sparked the changes in the structure of life and thought in Europe, the assassination of the king of France, Henri IV (Henry of Navarre), in 1610, was crucial in that it made salient the need to find a new foundation for civil society. Henri IV was tolerant of religious diversity and provided guarantees for the civil rights of religious minorities, who were primarily Protestant. Powerful Catholics feared that he secretly planned to weaken Catholicism, and they arranged to have him killed. His assassination was a rejection of religious tolerance. Given the tensions between faiths across Europe and the high political stakes involved, Henri’s assassination was taken as evidence that only force could resolve religious disputes. In 1618, the Thirty Years’ War began that involved most states of Europe and led to widespread devastation and a marked reduction in population. Among the elites, those with time to reflect and write, a pressing concern became how we can find certainty for knowledge and living that religion seemingly failed to provide.

Not only was there religious conflict, but the challenges to orthodox understanding of the natural world by Nicholas Copernicus (1473–1543), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), and Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) seemed to shake the foundations of knowledge laid down by Aristotle and his 13th-century Christian interpreter, St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). The calls by Sir Francis Bacon around the beginning of the 17th century for a science based on observation of the world and the collection of those observations into a coherent framework through inductive reasoning was also a challenge to orthodox thinkers. This context for the new philosophies placed the study of man within a naturalistic framework. While several philosophers were prominent, we have chosen two, Descartes and Locke, as our exemplars of the new natural philosophy. What linked these two preeminent thinkers was their quest to find a certainty that could underpin civil life.

René Descartes (1596–1650)

Descartes was 22 years old when the Thirty Years’ War began. Descartes’s mother died when he was young. He lived with his grandparents and his two older siblings because his father, a lawyer, worked some distance away. A precocious child, at age 8 he was placed in the Collège at La Flèche, a Jesuit school. When he graduated at age 16, he had probably received as excellent an education as was available at the time. He was schooled in the Aristotelian beliefs, for example, about the organic soul and the intellective soul. Only humans were blessed with the latter and its chief characteristic, reason.

Two cautions are needed as we proceed. First, Descartes was not a psychologist, nor was he a protopsychologist. He was a philosopher concerned with placing knowledge on a sure foundation and from that foundation constructing knowledge about how the Creation worked, including the human brain and body. Descartes’s worry about the certainty of knowledge was with him even as he finished school. What compounded this worry was the state of his world as a young man. As the long period of conflict that became the Thirty Years’ War continued, Descartes, along with other thoughtful people, perceived that the underpinnings of society were inadequate to support an enduring civil society. This, combined with the disputatiousness and inconclusive arguments of the leading philosophers and theologians of the day, led Descartes to seek a way to have certain knowledge.

His search led him to the method of doubt. Descartes decided to accept only those things that were so clear and distinct to him that there could be no possibility of doubt. As he later wrote, “Immediately I noticed that while I was trying thus to think everything false, it was necessary that I, who was thinking this, was something” (cited in R. Smith, 1997, p. 129). This led him to the famous phrase, cogito ergo sum, “I am thinking, therefore I exist.” For Descartes, the rational soul, the I, was central. From that point, then, an argument was made for the existence of God and God’s perfection as expressed in natural law. These indubitable facts, Descartes argued, were the foundation stones that made certainty of knowledge possible.

Second, Descartes was very much a person of his culture, time, and place. That is, he was a Catholic who sought avidly to keep his work within the bounds of orthodox belief. His adherence to Catholicism can be seen in his insistence that the mind is immaterial and the province of God. This meant that the soul (mind) is entirely distinct from the body. The soul is the seat of reason and directly amenable to divine influence; it cannot be reduced to materiality or explained in terms of mechanics. However, the implication of this is that all that is not soul can be examined in terms of mechanics and is amenable to explanations based in natural law. Descartes proposed that many functions previously considered to be mental and immaterial should be considered properties of the body. These included memory, perception, imagination, dreaming, and feelings; all of these were properties of the body and so could potentially be understood in naturalistic terms. This is the basis of what came to be referred to as the mind–body split or mind–body dualism.

To explain these functions, Descartes relied on an understanding of mechanics derived partly from then-recent discoveries in medicine—William Harvey’s (1578–1657) articulation of the heart as a pump for the blood—and from the artists and craftsmen of his time who had refined automata. Automata are self-moving mechanical objects, such as robots. Evidence shows that automata date from early in Chinese history, but they had been refined and made newly popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. The word “automaton” was coined in the early 17th century. Some automata that Descartes would have been familiar with included dolls that seemed to play musical instruments or enact a play. He also knew the royal gardens at St. Germain-en-Laye, outside Paris. There, using hydraulic pressure activated when visitors stepped on hidden plates, statues would move seemingly on their own. Descartes used the principle of this mechanical movement as a generative metaphor for understanding the functions of the body, including memory and other properties of the nervous system. He supposed that the cavities in the brain, the ventricles, were filled with animal spirits, which could flow through (hollow) nerves to effe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1: ORIGINS OF A SCIENCE OF MIND

- CHAPTER 2: EVERYDAY LIFE AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PRACTICES

- CHAPTER 3: SUBJECT MATTER, METHODS, AND THE MAKING OF A NEW SCIENCE

- CHAPTER 4: FROM PERIPHERY TO CENTER: CREATING AN AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY

- CHAPTER 5: THE PRACTICE OF PSYCHOLOGY AT THE INTERFACE WITH MEDICINE

- CHAPTER 6: PSYCHOLOGISTS AS TESTERS: APPLYING PSYCHOLOGY, ORDERING SOCIETY

- CHAPTER 7: AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE AND PRACTICE BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS

- CHAPTER 8: PSYCHOLOGY IN EUROPE BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS

- CHAPTER 9: THE GOLDEN AGE OF AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY

- CHAPTER 10: INTERNATIONALIZATION AND INDIGENIZATION OF PSYCHOLOGY AFTER WORLD WAR II

- CHAPTER 11: FEMINISM AND AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE SCIENCE AND POLITICS OF GENDER

- CHAPTER 12: INCLUSIVENESS, IDENTITY, AND CONFLICT IN LATE 20TH-CENTURY AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY

- CHAPTER 13: BRAIN, BEHAVIOR, AND COGNITION SINCE 1945

- REFERENCES

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX

- End User License Agreement