![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Veterinary Pathology

What is pathology?

Who ‘does’ pathology?

Anatomic pathology

Clinical pathology

Microbiology

Parasitology

Immunology

Toxicology

Veterinary forensic pathology

Government agency laboratories

Pharmaceutical laboratories

Pathology as an academic subject

Aims of Chapter 1

- To define pathology as part of (veterinary) medicine

- To define general pathology as part of pathology

- To briefly discuss how pathology is used everyday, and who uses it and where it is used

What is pathology?

The word pathology comes from two Greek words, Pathos – which literally means ‘experience’ or ‘something which one suffers’, but which in this context is used in terms of suffering from a disease, and -logy meaning ‘word’, ‘speech’ or ‘reason’. The suffix -logy is used in compound words (when it is added to another word such as in biology, physiology and entomology), and then it infers ‘study of’ or ‘science of’.

So, pathology is the branch of medical science that involves study of the causes of diseases, how they develop and their effects on the body. It encompasses any deviation from a healthy or normal condition in any living creature. There is even a branch of horticulture that involves study of pathology in plants.

In pathology, the effects of diseases can be studied at various levels: the whole body, the organs or tissues, cells and even within cells (at sub-cellular level) (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 What is pathology?

Pathology is the branch of medical science involving study of the causes of diseases, how they develop and their effects on the body.

Pathology includes consideration of any deviation from a healthy or normal condition, in any living creature (including plants).

In pathology, the effects of diseases are studied at various levels: the whole body, the organs or tissues, the cells and even within cells (at sub-cellular level).

Who ‘does’ pathology?

You might answer that question by saying pathologists do, and that is certainly correct. We will discuss pathologists in a moment, but the ‘pathologically trained’ professionals are not the only ones actively engaged in pathology. If you are working in general practice, you are too.

As we said at the beginning of this chapter, pathology involves not just study of what causes diseases, but also how diseases develop and their effects on the body. Every time you record the temperature, pulse and respiration of a patient, use a dipstick to test an animal’s urine, run an automated blood analyser, change the dressing on an infected wound, or advise an owner about flea control to help their cat’s red itchy skin, or diet to control diarrhoea in a sensitive golden retriever, you are assessing the deviation from a healthy or normal condition in the animal; you are assessing pathological changes. So, you and the vets, physiotherapists and others with whom you work use their knowledge of pathology. But there will be times when you require help from a pathology diagnostic laboratory to make the diagnosis; perhaps you need tests beyond the scope of your practice laboratory.

Pathology laboratories may be independent businesses, or they may be based at a university veterinary school, or they may be government agencies. The pathologists who work at these laboratories are often classified according to the type of diagnostic work they do, though a few will be all-rounders and will do everything!

Anatomic pathology

Anatomic pathologists study disease by looking at tissue and organs. This may be by performing post-mortem examinations (also called necropsies) and writing a post-mortem report, or by looking at tissues from live animals (called biopsies). Anatomic pathologists will look at the tissues or organs by eye (gross examination) to identify abnormalities, but also use histologic sections, mounted on glass slides to look at the tissue under the microscope (see Box 1.2).

Clinical pathology

Clinical pathologists assess disease in an animal by studying body fluids (such as blood, urine, joint fluid, abdominal tap fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and so on). They may look at the chemical composition (clinical biochemistry) or the types of cells in the fluid or in an FNA, using a microscope to study a stained smear of the sample on a glass microscope slide (this is called cytology). Clinical pathologists might spot bacteria or other infectious organisms in a cytology preparation.

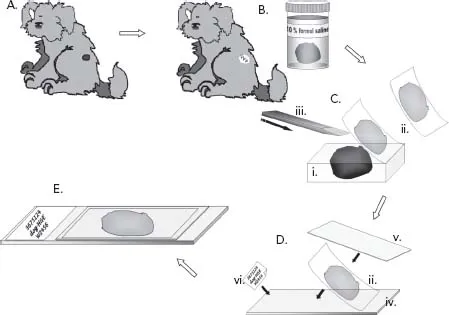

Box 1.2 How histology sections are produced (see diagram below)

A. A dog is presented at the vet’s surgery with a skin tumour.

B. Taking a biopsy, the vet decides to remove the tumour, perhaps after performing a fine-needle aspirate (FNA) and checking what the mass is. The vet and owner decide that they would like to send the mass to a pathologist to confirm the diagnosis. The mass is placed in a fixative solution which will preserve the tissue by fixing (denaturing) the proteins. Usually, a 10% solution of formalin is used (10% formol saline). In this example, the vet has removed (excised) the whole mass, this is called an excision biopsy. Sometimes only a part of a tissue is removed (incisional biopsy) and sent for histopathology. The biopsy is sent to the laboratory in a leakproof, wide-mouthed container.

C. In the laboratory, the tissue is processed by embedding it in a paraffin wax block (i). When this is done, very thin, almost transparent, slices of the tissue can be taken (ii), using an extremely sharp cutting instrument, called a microtome (iii). These slices are so thin that 1 cm of tissue could be sliced 5000 times.

D. A thin slice of the tissue is placed flat (mounted) on a glass microscope slide (iv), and dyed using histological stains. The standard staining method uses the stains haematoxylin and eosin (often shortened to ‘H and E’) which stains the sections pink and blue. The stains allow the pathologist to examine the tissues more easily than would an unstained section. The tissue section is protected by a very thin glass cover slip (v) which is glued on top. Finally, the slide is labelled with a reference number and other laboratory details (vi).

E. The pathologist examines the tissue section under the microscope and writes a report, which may suggest a diagnosis and prognosis. In the case of our dog’s tumour, the pathologist may also be able to tell whether the vet has managed to remove it all or whether further surgery at the site is advisable (the pathologist can tell this by looking at the edges of the tumour and observing whether there is a rim of normal tissue around the edge – the excision margins).

Haematology is specifically the study of cell types in blood, and this can indicate an increase in white blood cells (leucocytes) in an animal fighting an infection or a decrease in red blood cells (erythrocytes) in an animal with anaemia.

An anatomic or clinical pathologist may suspect that infectious organisms are involved in the disease and may suggest a fresh (unfixed) sample should be sent for microbiology (see below) if the practice has not already done this.

Microbiology

Microbiologists study infectious organisms that may be associated with diseases, more specifically, bacteriologists study bacteria, virologists study viruses, and mycologists study fungi and yeasts. Clinical samples, such as urine, pus, mucus or even tissue may be sent to microbiology laboratories where they have the equipment, skills and expertise to grow (culture) and identify infectious organisms. In the case of bacterial infection, they may also be able to assess which antibiotics the organism is likely to be killed by (the sensitivity of the organism) which gives the vet an indication of what treatment to use.

Parasitology

Although the very small creatures studied by microbiologists could be described as being parasitic, parasitologists tend to be associated with the study of slightly larger organisms which live on or in other animals. So, parasitology encompasses the study of, for instance, parasitic worms in the gut, fleas living on the skin or demodex mites living in hair follicles.

Immunology

Sometimes an infectious organism is suspected of causing disease in an animal, but that organism itself cannot be cultured in the microbiology laboratory or seen in samples under the microscope. In this case, the immunology laboratory may be able to tell whether the animal has been infected by the suspected organism by looking for antibodies. Antibodies are produced by the body’s immune system to help fight disease (this is part of what is known as an immune response); specific antibodies are produced for specific infectious agents, so finding certain antibodies will indicate that an animal has come into contact with a certain infectious agent (or has responded to a vaccine).

Infectious organisms have proteins on their surfaces, called antigens. These antigens are a sort of ‘fingerprint’ which the immune system can usually recognise as being ‘foreign’ and this stimulates the immune response. Sometimes specific antigens can be detected in samples by immunological tests.

Such immunological tests may be done on blood serum (this is called serology). Some immunological tests can also be carried out on tissues mounted on microscope slides, and this is then known as immunostaining. All types of cells of the body have their own ‘fingerprint’, though in a healthy individual the immune system recognises these and doesn’t start to react against them. Sometimes we can use this property of cells to confirm the diagnosis, for instance, if a pathologist is having trouble identifying a particular skin tumour under the microscope immunostains for specific cell types can be applied to the tissue and can help to reveal the identity of the tumour.

Toxicology

In some cases, toxicologists may be asked to analyse samples for toxins or poisons, for instance, you or the pathologist might send stomach contents, urine or even fresh tissue from a necropsy in the case of an animal suspected of being poisoned. The laboratory may need some guidance as to which toxic substance is suspected, such as a reliable history of known or likely contact of an animal with that particular substance. Note also that very often the toxins or poisons break down or are metabolised after having their damaging effects, and may not be detected in biological samples. In these cases, the animal presents with clinical signs that require diagnosis and treatment, such as a severely anaemic animal that has eaten anticoagulant rodent poison. The priority is to treat the anaemia, and toxicology may not be helpful, though it could be argued that confirming the cause of the animal’s signs may help to prevent poisoning in other animals.

Veterinary forensic pathology

There are a small number of veterinary pathologists who deal with forensic cases; that is, cases where there may be suggestions of cruelty or malicious harm to men or animals, or police involvement due to suspected illegal activity of one sort or another. This subject is beyond the scope of this book, and it is usually best for general practices to seek advice if they get drawn into such a case unless they are experienced in dealing with them. As a rule of thumb all those involved with the case, including veterinary nurses, may be asked to give evidence at a later stage, and should always keep notes, photographs, logged telephone calls or case records securely and safely stored, in case they need to submit them to the authorities as part of the investigation. Any biological material, including bodies of deceased animals, should be logged and labelled, and stored securely until removal by an authorised person.

Government agency laboratories

Some pathologists are employed as veterinary investigation officers, and work for government agency laboratories. These laboratories principally investigate diseases in farm or production animals. As well as investigating disease in individual or small groups of animals, these pathologists are important in helping to maintain herd or flock health on farms and nationally. This helps to prevent widespread infectious diseases and to protect our food quality (and safety) and human health.

Pharmaceutical laboratories

Veterinary pathologists work at pharmaceutical laboratories too. Here they will help to investigate diseases and to develop drugs to treat men and animals. They will also take an interest in apparent unexpected drug reactions.

Pathology as an aca...