![]()

PART I

The Basics

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Information Technology Planning Process

Robert Fabiszak

Accurate and timely financial information is essential to managing a modern corporation. Investors and regulators require periodic disclosures, while managers and executives rely on financial data for decision making and strategy. Businesses have no shortage of such information—in fact, the very volume and complexity of their financial data often presents a significant challenge to their ability to use it wisely. This financial data is maintained in a wide variety of information systems, ranging from sophisticated enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, to single-purpose tools such as financial consolidation systems, to the individual database on someone’s personal computer that generates an important journal entry each quarter.

In most companies, this array of financial systems and databases has been built up over time, sometimes with great foresight and planning and other times as an expedient reaction to a specific business need. As a business grows and becomes more complex, the difficulty in managing its financial information can also grow, oftendisproportionately. It can become more difficult to provide appropriate financial controls as transactions become more complex and new business models evolve. Duplicate systems can arise due to mergers, which often leads to inefficient operations and inconsistent data between systems. Responding to management requests for information can become more difficult as reporting databases and spreadsheets proliferate.

The task of managing these complexities largely falls on the information technology (IT) department. However, the chief financial officer (CFO) and the Finance function also play an important role in this process. They are not just passive users and producers of financial information. They must also be actively involved in financial system planning and decisions. This chapter will discuss some of Finance’s roles andresponsibilities with respect to information systems—in particular its role in information technology planning.

Finance and Information Systems

The role of the CFO and the Finance function has evolved over time. From mere bookkeepers who played a purely supporting role, Finance has evolved to become an integral part of the strategy and management of most companies. Regulations adopted in the shadow of Enron’s collapse, such as Sarbanes-Oxley, require CFOs to exert more control over financial data and to take responsibility for its accuracy. In order to assume that responsibility, which includes personally attesting to the accuracy of publicly reported financial results, CFOs have realized that they cannot simply accept financial data that they do not control. As a result, CFOs generally “own” their companies’ numbers: They have the primary responsibility for the data in financial systems, if not responsibility for the financial systems themselves. More important, Finance has become a strategic player in most companies, requiring it to analyze and understand the financial data to provide insights and strategic recommendations. This, of course, means that the appropriate data must be available, accurate, and accessible.

Every part of a company’s business processes ultimately impacts Finance. Certain processes, such as order-to-cash and procure-to-pay, are primarily the domain of Finance. But other processes, like procurement, customer management, manufacturing, and so on, also impact Finance, because it either uses or generates financial data. Thus, the systems that these processes use are at least indirectly financial systems as well. As the primary stewards and important consumers of the company’s numbers, the CFO and the Finance function are key stakeholders in the vast majority of a company’s information systems.

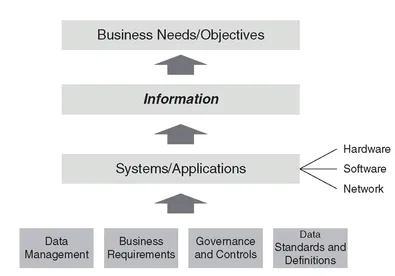

To better understand the linkages between Finance and information systems, it is useful to look at a conceptual model of a company’s systems and information environment. In this way, we can examine the role that Finance plays as both steward and consumer of information. Figure 1.1 shows a simple systems and information model.

FIGURE 1.1 Systems and Information Model

In this model,

information takes its rightful place as the central focus. This collection of financial data consists of three major components:

1. Master data. This is the set of codes and structures that identify and organize the data. Data elements such as customer codes, customer names, general ledger account numbers, employee IDs, and business unit codes and names are part of master data. All transactions and other business processes use this master data to identify the business entities impacted by the transactions. Most transactions use several different master data elements. For example, taking an order from a customer will involve (or create) such master data elements as customer number, address, order number, stock-keeping unit, salesperson ID, and so on. Master data elements can be arranged into hierarchies, such as a legal entity structure showing the ownership of each legal entity within a corporation, which is used for financial consolidation and external reporting.

2. Transactional data. This is the set of records of individual business activities or events. Transactions are associated with specific business entities (defined by the master data) and record the economic impact or value of the activity. A single activity may create a number of transactions or accounting records. Continuing the customer order example, taking an order will generate records in the order system and, upon shipment, will record revenue and a receivable as well. This transactional data is the heart of any financial system, and maintaining its accuracy and timeliness is a key Finance responsibility.

3. Reporting and analytical data. While the transactional data contains all of the financial records of a company, it is often difficult to use that data for reporting. A large company may have millions of transactions, which could make filtering and aggregating the data very time-consuming (not to mention slowing down the transactional systems). In addition, some reports or analyses will likely require data from multiple systems, which often have differing sets of master data, making it difficult to link data from one system to another. As a result, most companies have a data warehouse, or possibly a series of data marts, or some other type of reporting database to facilitate reporting and analysis. These reporting databases extract and, in some cases, transform data from the source (transactional) systems, and store it in a way that permits easier reporting. Data in these reporting systems can be aggregated using master data hierarchies to allow reports on rollup data to process more quickly. In addition, these databases can further support reporting and analysis by calculating and storing key performance indicators or other metrics, as well as by aggregating the data across a variety of dimensions, or slices of data (e.g., by legal entity, business unit, and geography).

In this model, the term information is preferred to data, because in addition to the transactional data, the model allows for the reporting and analytical data, to which some degree of financial intelligence and business rules have been applied. Just as Finance is the main steward of transactional data, it is a major consumer of financial data as well, and much of the value it adds to the strategic and management functions of the business derives from its ability to use this reporting and analytical data transformed into information.

All of this financial information is maintained and managed by a variety of systems. The systems and applications layer of the model includes all of the hardware, software, and network infrastructure that support business operations. The primary financial systems are generally part of an ERP system, and would include the general ledger, the receivables and payables modules, procurement, order entry, payroll, and others. However, most companies have other financial systems beyond their primary ERP, such as legacy systems from acquired companies and homegrown systems written to support specialized business situations. In addition, most companies have best-of-breed applications to support specific business processes, such as financial consolidation, budgeting and planning, reporting and analysis, and treasury management. Finally, in an uncomfortably large number of cases, companies maintain important financial information in desktop databases and spreadsheets. In fact, it is likely that most companies use spreadsheets to perform at least part of some key business processes, such as budgeting and planning.

The systems and applications are used to define and implement a number of important elements that go into maintaining financial information. These

foundational elements are shown in the bottom row of

Figure 1.1 and include:

• Data management. This represents the maintenance and management of master data, including the definition of links between systems. Master data management has become an area of emphasis for IT departments in recent years, and it is particularly valuable in environments with multiple interrelated systems. It also includes the mappings and interface rules required for one system to feed data to another or to a reporting database or data warehouse.

• Business requirements. This represents the rules implemented within the financial systems to process transactions and implement business logic. Business requirements can include implementation of accounting rules (such as elimination of intercompany transactions at the lowest common parent), definitions of business processes (such as the approval routing before a payment is issued), and specifications for outputs (such as regulatory or management reports). These business requirements are implemented through the configuration of the ERP or other financial system and through system and database code.

• Governance and controls. With the increased scrutiny of financial results and the need for greater transparency and governance in the wake of Sarbanes-Oxley, companies have built more automated controls into their financial processes. In some cases, these controls are implemented within the financial systems, such as requiring different individuals to enter and approve journal vouchers. Financial system governance and controls are an important part of a company’s larger risk management efforts.

• Data definitions and standards. As noted earlier, despite their best efforts, most companies have a somewhat fragmented financial system environment, due to legacy systems from mergers, one-off solutions, and desktop applications. In order to effectively manage and use financial information, consistent data definitions and data standards are required. This is particularly an issue with desktop reporting and analysis, where it is not uncommon for two analysts to walk into a meeting with two completely different sets of numbers for what is supposed to be the same report. Similarly, financial systems in separate divisions or business units may have been implemented differently, leading toinconsistencies in transaction processing and reporting. For example, one large payment-processing company conducted a worldwide ERP implementation with minimal corporate guidelines for data definitions and standards. As a result, it ended up with different and irreconcilable charts of accounts in each business unit, requiring a costly and time-consuming process to map business unit data to another, separate consolidating instance of the general ledger. More explicit and well-enforced data standards would have eliminated the need for this effort.

These foundational elements, along with the system and application environment and the information that they support, must serve the broader business needs and objectives. Many executives complain that despite an array of financial and business systems, they do not have the information they need to run their businesses. Well-managed enterprises, however, generally have a system environment that can support their strategic and operational objectives.

To further the objective of developing financial systems that provide timely and accurate information to support the business, most companies periodically develop an information systems strategy. This strategy then supports an Information Technology Plan that guides the company along the path of developing the appropriate system environment. The sections that follow describe the information technology planning process and Finance’s role in that process.

Information Technology Planning Process

Despite the best efforts of information technology departments, most companies’ information system environments are anything but stable and predictable. Business needs change. New co...