![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing a new age

The day is coming when great nations will find their numbers dwindling from census to census.

—Don Juan in George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman, Act 3, 1903.

The distinguished economist, author, and public servant J.K. Galbraith, who died in 2006 at the ripe old age of 97, referred some 10 years earlier to the “still” syndrome. He was reflecting on the way the elderly are reminded constantly about the inevitability of decline. The “still” syndrome, he said, was adopted by the young to assail the old as in “Are you still working?” or “Are you still taking exercise?” or “. . . still writing,” “. . . still drinking?” and so on. His advice was to have a retort ready to call attention to the speaker’s departure from grace and decency. His was to say, “I see that you are still rather immature.” He urged old people to devise an equally adverse, even insulting, response and voice it relentlessly.1

You can see Galbraith’s point. I do not wish to become embroiled in an argument about “agism,” but the fact that we can live and work longer than our parents and grandparents and that it looks like our children will do even better, reflects great improvements in health, education, technology, and economic growth. It is the consequences of that success that I propose to look at here. For, while we might like the idea of living healthier and longer lives, population aging brings with it very real economic and social problems.

In the very long run, the issue of population aging will probably fade. The baby boomers will move on to the great retirement home in the sky, and the global trend toward lower fertility rates will result in the restoration of better demographic balance. For the time being, however, we will have to face up to the problems created by such age and gender imbalances, and the divide between the old-age bulge of developed countries and the youth bulge of developing ones. Some communities and countries will deal with these challenges more successfully or with less disruption than others.

In some ways, you could see aging and population trends as more evidence of the West’s steady decline. While there may be some truth in this, the global and complex nature of population aging also means we must look at aging through different spectacles.

For the West the challenges that lie ahead will be formidable. They aren’t quite the same as those discussed in Decline of the West, a cyclical theory of the rise and fall of civilizations as foreseen by the controversial historian and philosopher Oswald Spengler in 1918.2 His rather prejudiced views—he believed in German hegemony in Europe and was seen by the Nazis as a sort of intellectual heavyweight—were set against a background of what he called the prospect of “appalling depopulation.” Today, it is population aging rather than depopulation that concerns us, along with the economic and social changes associated with a shift of power to the younger countries in the developing world, typified by China and India. These things are already influencing our perceptions of economic and financial security. As if this were not enough, younger people in Western societies will probably have to deal with a generational shift in feelings of prosperity and well-being. What seemed to come easily to the baby boomers will be less accessible to their children and grandchildren. How well Western societies and institutions cope with these changes is of great importance.

From a philosophical point of view, the quote from George Bernard Shaw’s play at the start of this chapter may be of interest. Drawn from a dream sequence, in which Don Juan and the Devil debate the relative benefits of Hell over its dull alternative, the passage also discusses love and gender roles, marriage, procreation, and the enjoyment of life.

Everyone is affected everywhere

Baby boomers will remember the term “swinging sixties” with nostalgia and some affection. Notwithstanding the restrictions in the 1960s on what you could do in public, this era of “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll” was essentially a public celebration of a golden age for youth and of rising political and social consciousness. Young people aspired to freedoms, rights, and means of expression that were revolutionary in the context of the environment in which they had grown up, even if not in the traditional context of the violent overthrow of government. In fact, the sixties may have been anything but swinging in some respects, but the impact of the boomers on social organization, political processes, and economic outcomes was unquestionably significant. What mattered was not so much the demand for change, but that it occurred in the context of an enormous increase in the proportion of young people in the population.

Time and age, though, have moved on and in many countries, for the first time ever, there are already more people of pensionable age than there are children under 16 years—and the difference is going to increase over the next 20 to 30 years. It is both apt and increasingly urgent, therefore, to focus attention on the different prospects and lifestyles faced by different generations.

If you were born before the end of the Second World War, the chances are you are retired or soon will be. You may worry about many things in your life, but financial security is probably not one of them, and your state and/or employee pension is most likely secure.3 If you were born after the Second World War but before say 1963, you are now on the cusp of retirement or within 10 or 20 years of it. Most of you should not have to worry too much about financial security, but some at the younger end of this age group are almost certainly going to confront the implications of population aging head-on.

Those who are Generation X, born between the mid-1960s and 1979, or Generation Y, born between 1980 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, or belong to the subsequent Internet Generation, are a large part of the focus of this book. They form what has been called the “boomerangst” generation. Although this term normally refers to the fears and concerns of the boomers themselves, it is also apt to apply it to their children and grandchildren. Indeed, it is a direct allusion to both some behavioral characteristics of younger people today and some of the financial and social issues with which they are growing up. For it is on their shoulders that the worrying burden and task of managing and coping with population aging will fall.

Although it is the macroeconomic implications of these changes that I examine in this book, there are many personal issues that people will have to confront that will affect both themselves and their elders. By way of background, consider just three: First, younger people today have higher divorce and separation rates. Nonmarried women are less likely than nonmarried men to have adequate financial security for retirement, but the latter have bigger problems in forming and maintaining social networks. Second, childless couples and single-parent families comprise a growing social class, and care for separated or single middle-aged women, as they age, becomes a more pressing issue when they do not have adult children to help. And third, support for the growing band of older citizens will become crucial. More and more over-65s will be living alone and belong to families that will be “long” in terms of generations and “narrow” in terms of the number of children, siblings, and cousins.

It would be wrong to think that these demographic issues are unique to the West. Many developing countries, while younger than Western societies, are aging faster, and most will confront similar problems from about 2030–35. Yet, for now at least, they lack the West’s wealth, social infrastructure, and financial security systems. Some developing countries, notably China and South Africa, will confront their aging issues—for quite different reasons—much earlier than most. For South Africa, the main problem is the devastating effect of HIV/AIDS on the mortality of younger, working-age people. In China’s case, it is because of the impact of the one-child policy, as well as other more common causes of declining fertility rates and rising life expectancy. China’s population aged under 50 and, by implication, much of its labor force, starts to contract around the same time as in Germany, in 2009–10. Despite our fascination and, for some, fear at the speed with which say, China and India, are becoming major world powers, it is possible that they too face a parallel to the West’s “decline.” Later, I shall explain that the reason for this slightly chilling warning lies in the interplay between aging populations on the one hand and a growing gender gap characterized by an excessive male:female ratio on the other.

Moreover, just because one country or region seems to be more youthful than another, you cannot assume that its economic prowess and potential is greater. Age—or youth—is important but always in context. For example, the so-called Tiger countries (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) were, in 1970, virtually indistinguishable from the main South American countries with identical age structures and median ages. Between 1970 and 2007 their populations of working age grew at almost identical rates. But over this period, income per head, which was about the same for both geographic regions in 1970, quadrupled in the case of South Korea and Taiwan, and rose sixfold for Hong Kong and Singapore, while barely doubling in South American countries. Demographic factors alone cannot explain this discrepancy, but the organization and marshalling of human (and other) resources by government, and agencies of the state, were unquestionably crucial to the Tigers’ success.

In considering the prospects for aging societies, therefore, it is important to understand not only the basic demographics of countries and regions but also a range of other economic, social, and political conditions and policies that could affect those population trends in a more or less positive way.

Although much of this book is about the macroeconomics of demographic change, there are no equations, and the concepts are pretty simple to understand. But demography reaches far into the microeconomics of how and why we spend and save, how we interact with work, family, and each other, and how we plan for retirement and old age, as well as into areas such as globalization, immigration, and international security.

Mostly, we just don’t think, or perhaps don’t like to think, about aging. Our consumer culture is dominated by images of youth, energy, dynamism, and sex. As population aging advances, however, it is inevitable that the youth intensity of this culture will change and with it our collective interest in the implications of older societies. Even now, rare as it is to hear demographics discussed at the pub or at a social event, popular interest is increasing: the affordability of pensions, for example, is now a widespread concern. We are at the start of a unique development in history and shall soon see how Western societies and some of the major “emerging” nations will cope. The West will have to figure how to manage and prosper with not having enough children to become tomorrow’s workers and breadwinners. Developing countries will have to create societies that offer employment and hope to their young before aging starts to manifest itself in about 2030–35.

The demographic debate laid bare

The book is divided into 10 further chapters. The first three discuss population issues from a historical and contemporary perspective. From Thomas Malthus, through Karl Marx and Charles Darwin to the baby boomers, the Club of Rome, and climate change, demographic developments have been and remain important even as the pendulum of public debate has swayed back and forth over time. What is new today are the large changes in age structure, brought about by rising life expectancy and falling fertility rates, and the silent but significant shifts in old-age and youth dependency.

Therefore, I consider the main characteristics of an aging world, and what their implications are, and ask how some of the economic consequences could be addressed. For the most part, these possible solutions fall into four categories: raising the participation in the workforce of people who could work more or longer but don’t; raising productivity growth so that those at work contribute more to society and the economy; sustaining or increasing high levels of immigration so as to make good possible labor and skill shortages; and paying attention to the inadequacy of savings, which, in many countries, threatens to cause financial problems when resources have to be transferred between generations to ensure adequate financial security for today’s and tomorrow’s retirees.

Differing prospects for richer and poorer nations

The next three chapters look at population and aging issues in more detail, first in the United States, Japan, and western Europe and then in emerging and developing countries. Japan is our laboratory for aging issues, and so developments there may hold lessons for the rest of us. Some are relevant, some not, but Japan’s relative slippage from the center of global affairs may have something to do with its rapid aging, especially in the company of large and populous neighbors. America’s circumstances are altogether different—as are those of some other, mainly Anglo-Saxon, countries.

In America, the aging of society is a slower process, and the country’s population is still expected to rise by 100 million over the next 40 years or so. But it is a country, a superpower, that is being stretched, not only militarily but also financially. It is already the world’s biggest debtor nation, presiding over a reserve currency that may be in slow decline. The key demographic issue for the United States, however, is the affordability and financing of not only pensions but notably healthcare. The European Union includes countries that are aging more rapidly, notably Italy and Germany, and some in which depopulation is already occurring, or soon will. Financing of pensions and improving the way labor markets work are already important policy issues for EU leaders and will dominate the national and EU policy agenda in the next decades.

The bigger and more macroeconomic implications of aging societies in the West follow, and I ask whether aging could damage our wealth. What should we expect will happen to inflation and interest rates as demographic change unfolds? What could happen in the equity markets and to the returns needed to accumulate adequate pension assets? And—hottest potato of the lot—what does demographic change imply for house prices?

Emerging and developing countries are of particular interest for a variety of reasons, not least because the bulk of the rise in the world’s population in the next 40 years is expected to occur in sub-Saharan Africa and in the arc of countries from Algeria to Afghanistan. The more pronounced characteristics of aging societies won’t become apparent to these countries until the 2030s. Until then, they will have strong demographic advantages, which give them the potential to wield both economic and political power. I shall discuss specifically the particular issues that await China, India, Russia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa.

Demographics and other global trends

The last three chapters consider the significance of demographic change in areas that are often overlooked in discussions about population and aging. Globalization defines the way in which countries and populations interact. It is neither static nor stable, however, and it is certainly vulnerable to reverses—or destruction, as occurred between 1914 and 1945. So how might aging societies evolve if the rising hostility to globalization in richer economies continues?

Immigration is an important way in which countries with advanced aging characteristics can supplement future labor or skill shortages. It is also an intensely political and emotional issue, and you can have some serious reservations about the practicality and usefulness of high or higher immigration in aging societies without being opposed to immigration. It is important to look at it in some detail and at the economic arguments advanced in its favor as a solution to the problems of aging societies.

Following on from immigration, religion and international security are hardly softer topics, but it is appropriate to consider some issues associated with both. So I look at whether the higher fertility rates associated with people with high levels of religious belief or practice mean that Western societies, for example, are, in effect, at the cusp of reversing decades or even centuries of secularization. There is also the contrast between the youth bulge in developing countries, some of which are, or aspire to be, powers, and the old-age bulge in the West, and how it provides a fitting backdrop to ponder the implications for global security.

Last, in the epilogue, I consider some big questions that might be faced by the baby-boomers’ children and grandchildren, the “boomerangst” generation. And in a postscript on population forecasting, I detail some of the main aspects of this particular branch of futurology.

Endnotes

1 Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, “John Kenneth Galbraith’s Notes on Ageing: The Still Syndrome,” http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-218599.

2 Oswald Spengler, Decline of the West, originally written in German, published in English, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

3 Many people have been shocked by events that have compromised or even destroyed what they thought to be secure pensions. One of the more celebrated examples concerned the thousands of employees who worked for a Houston-based energy company called Enron that went bankrupt after an accounting scandal in 2001. Because the employees were obliged to hold their pension assets in the company’s stock, the price of which collapsed, their pensions became worthless. There are many other examples of the dilution or destruction of pension plans as a result of corporate bankruptcy or takeovers but also because of changes to pension plans and eligibility.

![]()

Chapter 2

Population issues from Jesus Christ to aging and climate change

More generally … population and environmental problems created by nonsustainable resource use will ultimately get solved one way or another: if not by pleasant means of our own choice, then by unpleasant and unchosen means, such as the ones that Malthus initially envisioned.

—Jared Diamond, Collapse.1

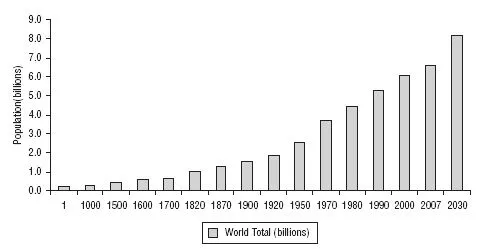

Around the time of the birth of Jesus Christ, and through the duration of the Roman Empire, the world’s population was probably no larger than 200 million. According to Angus Maddison, Professor at the Faculty of Economics, University of Groningen,2 Netherlands, world population was still less than 270 million in 1000. By 1700, however, the total had grown to about 600 million and by 1820, may have just surpassed one billion. Yet, it had taken two centuries to double. It took just over one century to double again to 2.3 billion in 1940. In 1960, world population was around 3 billion. Today, half a century later, it has more than doubled again to about 6.5 billion, and the United Nations expects it to reach 8.2 billion in 2030 and just over 9 billion by 2050 (see Figure 2.1).

Despite the fact that population has risen especially sharply only for the last 100 years, social commentators, philosophers, and economists have been looking throughout history at population trends. Edward Gibbon, in his renowned The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,3 suggested that the Roman Empire collapsed because it eventually fell victim to barbarian invasions on its periphery, which succeeded because of a loss of civic virtue among citizens in its center. Roman citizens, Gibbon argued, had become lazy, even “outsourcing” their duties to barbarian mercenaries, who became so numerous that they eventually overwhelmed the empire.

Figure 2.1 World population

Source: Angus Maddison, Groningen Growth and Development Center.

Gibbon’s account of social decay in Rome contrasts with what many see as the idealism, belief system, extended family focus, and higher fertility on the part of Christians. And in turn, said Gibbon, the characteristics and philosophy of Christians sapped the enthusiasm of Roman citizens to fight and sacrifice for the empire. Not a few observers have wondered if the West is today’s “Rome” but I shall come to that later.

In terms of population size, then, not much happened for the best part of a millennium and a half—well, not much by the standards of what happened in the second millennium. Population growth was slow and often interrupted by famine and disease, notably the Black Death, or Black Plague, in the mid-fourteenth century, which is estimated to have wiped out anywhere between a third and two-thirds of Europe’s population. The acceleration in population growth began after 1750 in England and then, with gusto, in mainland Europe after 1800.

Population take-off, Malthus, and Marx

Numerous theories have been proposed as to why this happened when it did. The Industrial Revolution is credited with being the main catalyst. It brought new technology, better diets and medical care, and, eventually, prosperity. But this standard explanation isn’t the whole story. Other noneconomic factors were important in stimulating population growth. These included a decline in the age of marriage in step with...