![]()

PART ONE

THE ESSENTIALS OF GLOBAL AND MULTICULTURAL NEGOTIATION

Part One examines in detail cultural factors that influence intercultural negotiations and problem solving. Chapter One explores the concepts of culture and negotiation and the intersection of the two. Chapter Two presents an important conceptual framework: the Wheel of Culture. The Wheel of Culture explores broad factors that shape the context and parameters in which negotiations occur, as well as specific variables, including cultural views toward relationships, communications, cooperation, competition, and conflict.

Chapter Three explores a range of possible strategies for responding to cross-cultural situations, examining the merits of adhering to your own culture, accommodating another cultural way of doing things, adapting to another culture, or developing new approaches that incorporate elements of both or all cultures involved.

Chapter Four looks carefully at a number of cross-cutting issues that will be referenced repeatedly throughout the remainder of the book, including key cultural variables, three main approaches to negotiation, the composition of negotiation teams, and the uses of power and influence.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction to Culture and Negotiation

The Context of Global and Multicultural Negotiations

Let’s look in on Alex, who is struggling to cope in a cross-cultural negotiation setting. Here is Alex’s message to people in his office. He might be a diplomat, a businessperson, or a development worker.

To: The Gang at the Office

From: Alex

Subject: Progress on negotiations for the new initiative

I thought I should give you all an update on how the talks about the initiative are proceeding. In my last message, I told you that our team had to meet the local leader prior to proceeding. Well, that meeting happened, and it was quite an event! Initially we were surprised to be met by a detachment of soldiers who we assumed were the leader’s personal bodyguards. They were all decked out in elaborate uniforms and rifles. They formed a corridor through which we walked to meet the leader, who was standing at the end of the column outside an elaborate audience hall and palace. He shook hands with all of us, introduced us to his wife, and invited us in to sit with them at a low table surrounded by chairs. (Naturally he and his wife sat in the largest and highest chairs!) He motioned to his servants, who rapidly brought tea and some sweets, some of which were unrecognizable and very chewy. The leader initiated some small talk, asking about where we were from, what we had seen of the country, what we thought of the culture, and so on, and we reciprocated the small talk. Finally, one person on our team tried to talk directly about the proposed new initiative, but the leader dismissively waved his hand and said that we should discuss it later with some of his colleagues. We took the hint and returned to small talk.

Upon adjourning our meeting with the leader, our team was shown into another large audience hall adjacent to the palace and seated at the head table on a dais at the front of a large conference room with fixed tables in the shape of a U. About twenty or thirty men and three women filed in behind us and took their seats around the U. A number of people, who we assumed were their subordinates, also stood around the outside of the room and kept constantly coming in and going out while delivering messages to or taking notes from their bosses, who conferred and signed papers. (This went on throughout the meeting.) Occasionally a cell phone would ring, and the recipient of the call would take the call where he was sitting, often talking in a fairly loud voice, or would rush to the back or out of the room. It felt like controlled chaos!

Finally, we were asked to make our presentation. While most people seemed to be listening, there were also a number of side conversations going on. When we finished, the local participants began a long and elaborate discussion in their own language that didn’t appear to have much focus either on us or on the program proposal. For long periods, they even seemed to be arguing among themselves. They occasionally asked us questions, but the discussion focused on several men who made fairly long, vociferous speeches, only portions of which were made in a language we understood or were interpreted for us. The group seemed to circle the question of whether to support our proposal, without ever explicitly supporting or rejecting it. I guess they wanted to get all of the views out on the table and assess the lay of the land without committing themselves. When it seemed appropriate, we added our comments and tried to answer their questions. Finally, one of the older men said he liked our ideas and suggested that talks continue at a later undefined time. I guess this will take longer than I figured! Please change my return air reservations to late next week. That’s all for now.

Alex’s message illustrates some of the difficulties of intercultural negotiations. Traveling businesspeople, diplomats, and development specialists writing to their home offices find that formal ceremonial events, a confusing decision-making process, and unclear power dynamics leave them stymied about how to proceed. Certainly local counterparts approach the negotiation process in ways that are strange—but are completely normal to them, of course.

This book is about the intersection between culture and negotiation. People who work across cultures, whether internationally or within nations, need general principles—a cultural map, if you will—to guide their negotiation strategies. Such a map will help them to:

• Identify the general topography of cultures—the beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, procedures, and social structures that shape human interactions

• Recognize potential hazards, obstacles, and pleasant surprises that intercultural travelers and negotiators might miss without a guide

• Select responses that will be more likely to achieve successful interactions and outcomes

Although many books have been written about the negotiation process and many more about culture, few analytical frameworks provide practical guidance about how individuals, groups, and organizations from different cultures solve problems, negotiate agreements, or resolve disputes. This book addresses this gap.

A DEFINITION OF CULTURE

Culture is the cumulative result of experience, beliefs, values, knowledge, social organizations, perceptions of time, spatial relations, material objects and possessions, and concepts of the universe acquired or created by groups of people over the course of generations. It is socially constructed through individual and group effort and interactions. Culture manifests itself in patterns of language, behavior, activities, procedures, roles, and social structures and provides models and norms for acceptable day-to-day communication, social interaction, and achievement of desired affective and objective goals in a wide range of activities and arenas. Culture enables people to live together in a society within a given geographical environment, at a given state of technical development, and at a particular moment in time (Samovar and Porter, 1988).

When we think of culture, we often think exclusively in terms of national cultures that are often reported in the media. However, we find cultural differences at many levels. For instance, women and men constitute the two largest cultural groups in the world (Gilligan, 1982). We also encounter subcultures in the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of ethnic groups, regional groups, social classes, tribes, clans, neighborhoods, and families (Kahane, 2003; Sunshine, 1990). Governments and their agencies, corporations and private firms, universities and schools, civil society and nongovernmental organizations have their own specific cultures and ways of doing things, often called organizational culture (Deal and Kennedy, 1982; Schein, 2004). Culture is also rooted in religious beliefs, ideological persuasions, professions, and professional training and in the levels and types of education (Smith, 1989; Sunshine, 1990). Finally, families have cultures that are a blend or combination of the cultures of their adult members or of their extended families (McGoldrick, Giordano, and Garcia-Preto, 1982, 2002).

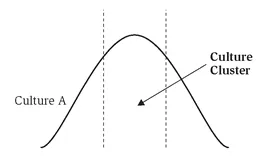

Given all of these cultural variables and significant variations within cultures, how can we develop any conclusions about how a particular person or group from any one culture might behave in negotiations or conflicts? Despite the apparent insurmountable scope of the problem, specific cultures do contain clusters of people with fairly common attitudinal and behavioral patterns. These culture clusters occupy the middle portion of a bell-shaped curve (Trompenars, 1994), such as that illustrated in Figure 1.1.

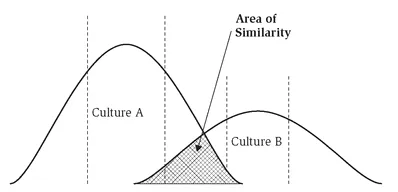

However, every culture includes outliers—people who vary significantly from the norm and are outside the cultural cluster. Although they are still contained within the range for their culture, their views and behaviors differ significantly from those of their peers and may even look similar to those of people from other cultures. For instance, a businessperson or engineer from a developing country who was educated in the United Kingdom and has lived there for many years may have more in common with his or her peers in Europe than with people in his or her country of origin (Figure 1.2).

For this reason, we must be wary of making vague or sweeping generalizations about how people from a specific culture may think or act. Rigid notions about a group’s cultural patterns can result in potentially inaccurate stereotypes, gross injustice to the group, and possibly disastrous assumptions or actions. Common elements and repetitive cultural patterns found in a group’s central cultural cluster should be looked on as possible, or even probable, clues as to the ways that members of a cultural group may think or respond. However, the hypothesis should always be tested and modified after direct interaction with the individual or group in question. You never know when you may encounter an outlier who acts out of cultural character, does not follow expectations according to stereotypes, and may think and behave more like you than you ever expected.

Figure 1.1. Distribution of Cultural Patterns in a Specific Group

Figure 1.2. Overlaps and Differences Among Cultures

Source: Trompenars (1994).

WHAT IS NEGOTIATION?

Before exploring the characteristics and cultural aspects of negotiation, we need a general definition of the term. Generally most Western negotiators and academics, when defining negotiation, emphasize the presence of incompatible positions or preferred solutions, a bargaining or problem-solving process based on an exchange of positions to address contested issues, or a process that results in specific tangible outcomes or substantive exchanges.

For example, Albin (2001, p. 1) states, “Negotiation is a joint decision-making process in which parties, with initially opposing positions and conflicting interests, arrive at a mutually beneficial and satisfactory agreement. It normally includes dialogue with problem-solving and discussion on merits, as well as bargaining and the exchange of concessions with the use of competitive tactics.” Although this definition does identify some of the key characteristics or elements that may be present in negotiations, it fails to accommodate the full range of negotiation goals, approaches, procedures, and outcomes found across cultures. We explore some of these variables later in this chapter.

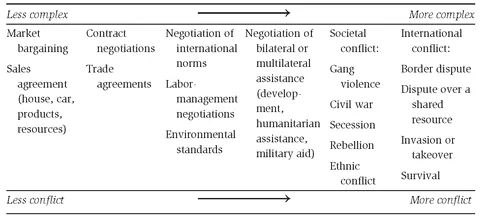

Within a broad definition of negotiation, we should also note that negotiations take place in a wide range of contexts, from simple market bargaining to complex processes to end wars within or between nations. Table 1.1 presents a schematic range of situations in which people from different cultures often engage in negotiation.

Table 1.1. Range of Negotiation Contexts

The examples in the table represent both simple and complex situations and ones that involve less or more conflict. Note, however, that situations of relatively little conflict can easily become contentious and move toward the right side of the table. For instance, trade negotiations are usually held in an atmosphere in which both sides are looking for mutual gain. However, if there has been recent perceived unfairness or disputes over certain kinds of goods, trade negotiations can become more contentious. And interactions that are generally straightforward in the context of a single culture can swiftly become conflictual due to intercultural misunderstanding. A European tourist might seek to purchase a carpet from a merchant in the market in Turkey. The interaction could begin amicably, with tea served and many carpets brought out for display. Although both buyer and seller expect a degree of over- and underbidding, either party might become angry based on perceived unfairness. A simple purchase can plunge into an irritated exchange.

Although the concepts in this book are applicable in all of the situations depicted in Table 1.1, they are most useful for more complex negotiations. The later chapters provide step-by-step practical guidance for all stages of negotiations. Such elaborate detail would be of little use for relatively simple transactions, but it becomes increasingly necessary as the stakes become higher and the level of actual or potential conflict rises.

CULTURAL VARIATIONS REGARDING THE ESSENTIAL PURPOSES OF NEGOTIATIONS

Members of different cultures see negotiations differently. For instance, some cultures place great emphasis on building positive relationships among negotiators—perhaps greater than their attention to any specific substantive decision or outcome. Many cultures also emphasize preexisting commonalties or areas of agreement or connections and procedures that develop consensus, as opposed to the exchange of positions or the use of threats. As we will see in later chapters, this difference in the basic conceptualization of negotiations can be considered a cultural frame.

Because of the range of cultural conceptions about what negotiations signify, the divergent goals that are influenced by culture, and the vast range of procedures and practices involved, we need a broad definition of the negotiation process and its potential outcomes. Our working definition of intercultural negotiation, used in the remainder of this book, is detailed in Box 1.1.

Although these elements occur in almost all negotiations, different cultures emphasize or value different parts. We now examine the elements of this definition in more detail and explore how the components of negotiation interact with culture.

Negotiation Is a Relationship-Establishing and Building Process

Negotiation occurs in the context of relationships: preexisting or newly created affiliations between individuals or groups. Relationships either bind parties together through common positive feelings of trust, respect, caring, obligation, or love, or drive them apart because of mistrust, pain, or hate. Constr...