![]()

Chapter 1

The Changing Face of Animal Ethics

This is a book about animal ethics. It describes and explains different views about how we – as human beings, capable of moral thought – ought to treat the animals in our care. However, a sober discussion of this issue must take as its starting point the way in which we do as a matter of fact treat the animals in our care and the attitudes we have towards these animals. This factual background is not static. The relationship between humans and animals has changed dramatically over the last 100 years or so, and remarkable changes have followed in the attitudes that humans have towards animals. The aim of this chapter is to describe these developments.

A major distinction will be drawn: there are traditional forms of animal use, where animals and humans live more or less symbiotically, and where the mutual dependence places limits on the kind of things humans do to animals. Here the main problem is the cruelty of people who, for no good reason, maltreat animals in their care. This problem will be described in the first section below. The second section will focus on recent developments in intensive animal production. These developments have brought about a situation in which animals in industrialised countries are put under extreme pressure in an effort to produce cheap products for an increasingly wealthy population. This section will also look at developments in laboratory animal science, where animals are used as research tools and, particular, as models of human diseases.

At the same time, the way in which we keep animals as pets or companions has also changed considerably, and interest in wild animals and the environment in which they live has grown. We tend to regard these animals completely differently from the way we regard livestock and laboratory animals. Developments in attitudes towards pets and wildlife will be described in the last section of this chapter.

Traditional ways of using animals and the emergence of anti-cruelty legislation

Within the mainstream of Western culture, animals have traditionally been viewed as means of fulfilling human needs. Such a view is expressed in the following part of Genesis:

God blessed Noah and his sons and said to them: ‘Be fertile and multiply and fill the earth. Dread fear of you shall come upon all the animals of the earth and all the birds of the air, upon all the creatures that move about on the ground and all the fishes of the sea; into your power they are delivered. Every creature that is alive shall be yours to eat; I give them all to you as I did the green plants’. (Genesis 9:1–4)

Of course, there are also places in the Bible where it is said that humans have duties towards animals, but this reminder did not figure much in official Christian theology. The highly influential philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), whose ideas still play an important role within the Catholic Church, argued that the parts of the Bible that seem to command that one should take care of animals are, in essence, about caring for humans. Not only are there humans whose property may be harmed if animals are maltreated, but cruelty to animals may also lead to cruelty towards humans. However, according to Aquinas, animals have no moral standing in their own right: they are there for us to use as our needs dictate (from Linzey & Regan 1990).

Until the nineteenth century, animals in the Western world were legally protected only in their capacity as items of private property. Bans on mistreatment were there to protect the rightful owner of the animals from having his property vandalised. Legally speaking, the animals themselves had no right to be protected.

Things began to change in the nineteenth century. This was a reflection of more general ethical and political changes that had taken place in the eighteenth century – a century in which grand ideas of human rights and liberal democracy gained momentum. It was no longer accepted that the ruling classes could treat the lower classes in the way they treated their property. Together with revolutions in France and the USA, the idea developed that all humans are equal, and that the role of the state is to protect the rights of all its citizens. This perspective is expressed in this famous statement from the American Declaration of Independence of 1776:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

With this new focus on the ‘safety and happiness’ of each individual human being it becomes possible to raise questions about the safety and happiness of the animals in human care. Whereas in the case of humans the focus is on political rights that allow people to pursue their own happiness, with animals (as with some weak or marginalised groups of humans) it does not seem to make sense to allow them to sort out things by themselves. Rather, in the various movements ‘for’ animals that developed around the beginning of the nineteenth century, the aim was to place limits on what humans were allowed to do with, or to, animals in their care. The aim was animal protection rather than animal rights.

Of course, these developments were not driven by ideas alone. It also mattered that with growing urbanisation large parts of the population no longer lived in the countryside and so no longer took part in traditional rural pursuits. Moreover, it mattered that there was a general increase in average levels of wealth in many countries. Clearly, people who have enough to eat and do not have to strive daily to subsist are in a better position to discuss the welfare of animals.

All these conditions were in place in early nineteenth-century England, where the world’s first law for the protection of animals was passed. Getting the law through both chambers of the parliament was a huge struggle for the two key figures in this reform, Richard Martin MP (Member of Parliament) (1754–1834) and his collaborator Lord Erskine (1750–1823). They were up against strong opposing interests, and a political climate in which many people found concern for animals effeminate and ludicrous (notice that at that time women had no role in political life). The formulation of the bill that finally passed through the British parliament in July 1822 was therefore, in many respects, a political compromise. The bill said:

that if any person or persons having the charge, care or custody of any horse, cow, ox, heifer, steer, sheep or other cattle, the property of any other person or persons, shall wantonly beat, abuse or ill-treat any such animal, such individuals shall be brought before a Justice of the Peace or other magistrate. (Ryder 1989, p.86)

There are three striking limitations here: (i) only some kinds of animal are covered; (ii) only things done by people who do not own the animals are covered; and (iii) only what is described as wanton cruelty is covered. (The adjective ‘wanton’ means undisciplined, random or motiveless, so those who passed this bill do not seem to have been aiming to place limits on established uses of animals. This contrasts with modern animal protection legislation.)

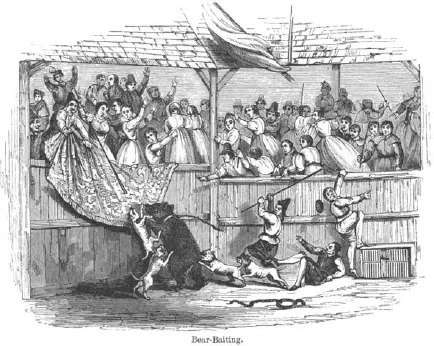

On the first point, it is striking that a number of species are not mentioned at all: for example dogs, cats, pigs and poultry. Even among the species mentioned, some kinds of animal, like bulls, are not mentioned explicitly. One reason for this is that, at the time, there was a custom of arranging fights between animals: cock fights, dog fights and bull or bear baiting (in which dogs attacked a chained bull or bear). These forms of ‘sport’ could be extremely cruel. In 1878 an English eye-witness described a bull baiting at which he had been present as a boy as ‘the most barbarous act’ he ever saw. ‘It was [a] young bull and had very little notion of tossing the dogs, which tore his ears and the skin off his face in shreds, and his mournful cries were awful. I was up a tree, and was afraid the earth would open and swallow us all up!’ (http://www.oakengates.com/history.htm).

Despite their cruelty, bull baiting and other blood sports were popular, and politicians at the time, as they often are today, were reluctant to make unpopular laws. Richard Martin, who clearly was not afraid of opposing the popular will tried, on the basis of the law, to have two bull baiters convicted, but he did not succeed. Only in 1835 was a bill passed that banned a number of blood sports. One prominent blood sport, fox hunting with dogs, was only recently outlawed in England (in 2005) and blood sports such as bull fighting and cock fighting are still common in some countries.

Figure 1.1 Bear baiting – a form of blood sport once popular in Europe, and still practised in some parts of the world, in which a tethered bear would fight a number of dogs. In this engraving from late eighteenth-century England, things are out of control because the bear has got loose. In 1835 bear baiting was banned in England because it involved ‘wanton cruelty’. (Engraving reproduced from John Brand, Observations on Popular Antiquities, London, 1841.)

Another reason that not all animal species are covered is that there clearly is a hierarchy of animals – a moral ordering that has been called the sociozoological scale (Arluke & Sanders 1996). The point of the scale is that people rate animals as morally more or less important, and therefore more or less worth protecting, according to a number of factors. These include how useful the animal is, how closely one collaborates with the individual animal, how cute and cuddly the animal is, how harmful the animal can be, and how ‘demonic’ it is perceived to be.

In early nineteenth-century England, horses and cattle were at the top of the sociozoological scale. Today, in western societies, clearly pet animals, notably dogs and cats, seem be at the top of the scale. At the same time stray dogs and cats are considered pests; and many people still see cats as somewhat demonic. The cat thus has a more ambiguous status. Horses are still at the top of the scale, but in a different role than they had previously. They used to be utility animals; now the horse is more of a companion animal. At the bottom of the scale are ‘pest’ animals: vermin, such as rats and mice. Chicken, which are considered stupid, and fish, which are cold and slimy, also appear to be quite low down the scale.

Whether an animal belongs to a species at the top or at the bottom of the sociozoological scale has clear implications for the view and treatment of the individual animal. For example, pets are usually given names. This is a clear contrast with utility animals, which are typically given a number or, if of a smaller species such as poultry, are simply counted in a weight per area ratio. Thus, where a dog is typically seen as ‘someone’ (that is, an individual), a chicken may be perceived as ‘something’ (that is, a mass). This difference in views on animals is understandable: it is impossible to establish a personal contact with every individual animal at a farm of a certain size. However, the view of an animal, reflected in assigning a name may indirectly have serious consequences for the animal’s welfare. In all likelihood, many people are more inclined to care for an animal that is considered someone (i.e., has the status of an individual with its own interests in life) than an animal that is anonymous or even reduced to the status of an object.

The sociozoological scale is in many ways based on traditions and prejudices, and its use as a basis for animal protection can be criticised on both scientific and ethical grounds. The point being made here is just that the scale is part of social reality. This reality is, among other things, reflected in the legislation that has been introduced to protect animals.

The second striking point about the 1822 bill mentioned above was that it only protected animals against things done by people other than the owner. This, of course, partly reflects a political reality, since those in power were typically the owners of land and livestock; by making sure that these people were not affected by the law it was easier to get it through both chambers of the parliament. However, there is another, more respectable reason, and this is related to the third of the mentioned limits in the scope of the 1822 law, namely that it only protects animals against ‘wanton’ cruelty.

The bill’s advocates assumed that the animal owner wants to protect and make good use of his property. To a great extent, the way to do this is by treating the animals well. So bad animal treatment is seen as something that is irrational, or pointless, which can only be done by someone who does not share the owner’s interest in protecting the value, that the animal represents. This point has been made by the American philosopher Bernard E. Rollin (b. 1943):

For most of human history, the anticruelty ethic and laws expressing it sufficed to encapsulate social concern for animal treatment for one fundamental reason: During that period, and today as well, the majority of animals used in society were agricultural, utilized for food, fiber, locomotion, and power. Until the mid-20th century, the key to success in animal agriculture was good husbandry, a word derived from the old Norse term for ‘bonded to the household’. Humans were in a contractual, symbiotic relationship with farm animals, with both parties living better than they would outside of the relationship. We put animals into optimal conditions dictated by their biological natures, and augmented their natural ability to survive and thrive by protecting them from predation, providing food and water during famine and drought, and giving them medical attention and help in birthing. The animals in turn provided us with their products (e.g., wool and milk), their labor, and sometimes their lives, but while they lived, their quality of life was good. Proper husbandry was sanctioned by the most powerful incentive there is – self-interest! The producer did well if and only if the animals did well. Husbandry was thus about putting square pegs in square holes, round pegs in round holes, and creating as little friction as possible doing so. Had a traditional agriculturalist attempted to raise 100,000 chickens in one building, they would all have succumbed to disease within a month. Thus, husbandry was both a prudential and an ethical imperative, as evidenced by the fact that when the psalmist wishes to create a metaphor for God’s ideal relationship to humans in the 23rd Psalm, he uses the Good Shepherd, who exemplifies husbandry. ‘The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside still waters; he restoreth my soul’. We want no more from God than what the Good Shepherd provides to his sheep. Thus, the nature of agriculture ensured good treatment of animals, and the anticruelty ethic was only needed to capture sadists and psychopaths unmoved by self-interest. (Rollin 2005, p. 16)

What is said here may in some ways be an overstatement. Negligence towards animals was, of course, not uncommon in the past, and there would have been cases of obvious conflict between the interests of the animals and the interests of the owners. The use of animals for blood sports such as bull baiting is an obvious example of this. Rollin also refers obliquely to slaughter without comment although, obviously, this is the point at which the farm animal’s living needs become irrelevant to the farmer. However, in general, people in the past had to treat their animals decently to get the most out of them; and in many ways it can be said that people and their animals lived under the same conditions in mutual dependence. This remains the case in some third world countries. One example is the Fulani people from a region of West Africa where the economy is to a great extent based on free-range grazing cattle. The system is described in the following way by two researchers:

the animal’s needs in terms of leading a natural life are met to a large extent, while confinement is minimized. Human dependence on the animal herd is vast under pastoral conditions, since animals and animal products are almost the only source of income in the subsistence economy of pastoral people. This strong reliance on pastoral animals results not only in extensive care but even in human affection of animals. (Doerfler & Peters 2006)

So to the extent that we and animals have shared interests, the need to protect animals can be equated with the need to protect animals against pointless cruelty. This equation underpinned most legislation aimed at protecting animals until at least the 1950s. It was only after this that attention turned in a serious way to the protection of animals ...