This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Edited by IP communications expert Bruce Berman, and with contributions from the top names in IP management, investment and consulting, From Assets to Profits: Competing for IP Value and Return provides a real-world look at patents, copyrights, and trademarks, how intellectual property assets work and the subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which they are used for competitive advantage. Authoritative and insightful, From Assets to Profits reveals the most relevant ways to generate return on innovation, with advice and essential guidance from battle tested IP pros.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access From Assets to Profits by Bruce Berman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Intellectual Property Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART 1

IP Business Models

CHAPTER 1

Out of Alignment—Getting IP and Business Strategies Back in Synch

BY DAN MCCURDY

PERSPECTIVE The desire to extract decisive returns on innovation is clouding many companies’ judgment. In an environment, where inventions have greater impact and court cases and legislative reform are weakening the value of many patents, confusion reins about what constitutes the proper way for a CEO or board of directors to behave.

Dan McCurdy contends that most business executives are ill-equipped to use patent strategy or understand the IP marketplace. Often, they fail to deploy intellectual assets for their true value. He also believes that IP executives have done a poor job of conveying IP imperatives to senior management, especially those in the C-suite, and to shareholders.

“In virtually all other aspects of business, executives fully grasp the requirement to knit together various elements of business operations into a cohesive whole,” says McCurdy, a licensing executive turned defensive strategist.

“They understand how to use a company’s equity, its cash, real estate, human resources, global reach, supply and distribution chains, marketing prowess, customer relationships, personal relationships, banking relationships, and government relationships to advantage their business. But, curiously, they do not understand—or generally even have much curiosity about—how to use to their advantage perhaps their most valuable corporate asset—their intellectual property.”

McCurdy suggests that better alignment (or realignment) of IP strategy with business objectives starts with people. It includes having IP and senior corporate executives communicate better by getting to know one another and understand the challenges they each face. McCurdy believes it is important they not fear each other—their company’s future may depend on their ability to collaborate.

THE CEO’S DILEMMA

The new millennium brought a flurry of activity and anxiety that has infused the global intellectual property community with both fear and opportunity. It is spilling over into the highest levels of corporate leadership. The anxiety is largely the result of mixed signals about how IP can impact business operations. Most business executives view intellectual property more as a problem likely to happen than an opportunity waiting to be unleashed. While there are a significant number of CEOs who have become aware of the profit-building business models of successful licensing companies such as IBM, Lucent, Philips, Thomson, Kodak and, more recently, Hewlett-Packard, a greater number of executives are becoming aware of the complexities and unpredictable outcomes that the licensing of intellectual property presents.

There was a time when companies that invested heavily in research and development and produced useful inventions that found their way into the products of others could collect significant royalties from infringers. Even then the battles were protracted and risks were present, but in the end the “first mover advantage” of a patentee seeking a royalty from a likely infringer was powerful and generally decisive. Thrown off balance by the attack, the potential licensee was frequently unable to regain its footing. After a few technical and business discussions that typically stretched across 12 to 24 months, the licensee caved and paid the aggressor a sum that was less than the royalty sought by the patentee, but much more than the tax expected by the licensee.

As this practice circulated around various high-tech industries for a couple of decades, old-time CEOs grew accustomed to it. However, entrepreneurial New Age CEOs of highly successful companies were not so accommodating. They viewed “expansionist” patent enforcement as a rip-off. The modus operandi of these executives was to hire exceptionally smart people who were in tune with market needs and who would create products that solved important problems confronting their customers. These engineers were not reverse engineering the products of competitors seeking to steal their innovations, but rather were independently solving important problems facing their customers through the creation of new technologies. They knew their solutions—novel in their minds—would drive huge sales of problem-solving products.

It is possible that the solutions they independently created would unknowingly share some of the concepts of an invention previously made by another. The fact that someone else had come upon a similar (or even nearly identical) idea first, and had patented that invention, now created an obstacle to the use of this similar, independently created idea. Indeed, neither inventor had copied the idea, but nonetheless the first inventor was in a position to disrupt the latter invention’s use. This dynamic was particularly troublesome in high-tech companies, where hundreds—possibly even thousands—of inventions were synergistically combined into a system such as a laptop computer to provide a solution to a problem. Contrast this with a pharmaceutical innovation, where the discovery of a new molecule could cost as much as U.S. $1 billion but alone could create tens of billions of dollars in revenue—or nothing. Infringement of such a pharmaceutical discovery was also more difficult because any resulting product would be subject to a dense minefield of regulatory oversight that would discourage or even prohibit such infringement, at least in countries enforcing their patents.

With this backdrop, put yourself in the shoes of a CEO. On the one hand, shareholders would argue that Lou Gerstner and Marshall Phelps at IBM made nearly $2 billion dollars annually at the height of the IBM licensing program, most of which was pure profit, by offering IBM patents and technology to licensees (see Exhibit 1.1). But on the other hand, the world is increasingly littered with jury verdicts against significant product companies, ordering them to pay monstrously huge royalty payments to companies with smaller revenues, and with patent trolls, who successfully enforce their patents against the much larger “Goliath.”

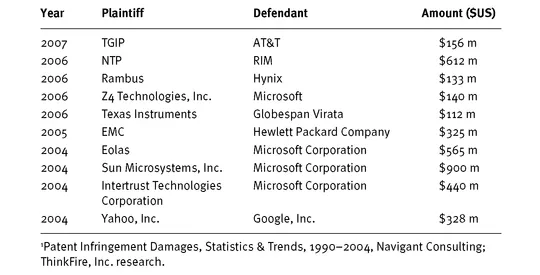

EXHIBIT 1.1 SELECTED HIGH TECH PATENT LITIGATION AWARDS AND SETTLEMENTS, 2004-20071

In the mind of a CEO bent on success, a modest amount of revenue and profit can be derived from adversarial IP licensing, versus the amount of revenue and profit that can be derived from the sale of successful products and services. And yet the risk of a counterclaim that could impose a significant tax, or shut down a major product line, is ever present. Moreover, the distraction to technical, marketing, sales, and operational staffs caught up in the discovery phases of patent litigation have a major impact on product operations.

For this reason some CEOs, such as Steve Appleton of Micron and John Chambers of Cisco, have long concluded that building a strong offensive patent position ensures that their executive and operational staffs are not disrupted by the tedious intricacies of patent litigation, enabling personnel to give their full attention to building valuable products that solve problems that will make their customers more successful. Others have reached the conclusion that their resources will allow them to build such products and services and obtain royalty revenues from the use of their most valuable inventions. The jury is out, both literally and figuratively, as to the correct decision. This is the CEO’s dilemma. Over the past decade the actions of patent speculators have further magnified the risks that patents play in innovative business operations.

THE EMERGENCE OF PATENT TROLLS, AND THEIR IMPACT ON IP LICENSING

At the turn of the 21st century, patent speculators, sometimes called patent trolls (or worse) began to grow in number and expand in capability. Their growth was driven by a perfect storm of intellectual property made available by the bursting dot-com bubble, significant capital, and massive revenues to be taxed by speculators intent on buying patents and enforcing them against product-producing companies. Operating companies, awakened with a jolt from their détente, were suddenly confronted with an adversary that did not respond to the IP skills and knowledge they had honed over the prior decades. The formula these operating companies had developed to deal with patent disputes with other operating companies no longer applied. They were up against an enemy they did not know, that used tactics they did not understand, that struck without warning, and that was invulnerable to a patent counter-attack.

Those product-producing companies that had developed active patent licensing programs, such as the aforementioned IBM, Lucent, Texas Instruments, Kodak, Thomson, and Philips to name just a few, each in a sense a patent “hunter” seeking royalties from those who used their inventions, were now the potential prey of a new breed of adversary. The patent landscape was changing again, requiring companies worldwide to develop new mechanisms, tools, and techniques to adapt to this environment. While the companies exposed are screaming “foul,” the fact is that this environment has exposed innovative companies since the patent laws were written into the U.S. Constitution more than 220 years ago. Charlatans of one sort or another have been exploiting the patent system ever since. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

The destabilizing impact of patent speculators has been, on the one hand, both significant and, on the other hand, potentially based on unfounded hysteria. There are now estimated to be more than 800 identified patent trolls, more than 200 of which are unaffiliated with one another. This excludes independent inventors and small companies pursuing patent enforcement of their inventions as a result of a failed attempt to produce and/or market a product embodying the invention. Operating companies almost universally agree that a patent troll is any entity that attempts to enforce a patent against them and is not vulnerable to patent counter-assertion because they have no or an inconsequential amount of product sales. In this broad definition, patent investors, law firms that accumulate and enforce patents, failed companies, individual inventors, research institutions, and even universities would largely qualify. Madey v. Duke adds an interesting twist to this debate.1 Given this broad definition, there are clearly thousands of “patent trolls” worldwide that pose a potential threat to successful product-producing companies.

With the exception of research institutions, universities, and independent inventors, patent trolls generally are dependent upon purchasing or otherwise gaining enforcement rights to patents created by others as the weapons of their trade. In the case of most research institutions and universities, while their threat may be significant, their patent portfolios are generally “a mile wide and a millimeter deep,” which is sometimes enough to pose a credible threat. With independent inventors, their patent portfolios tend to be a millimeter wide and perhaps a millimeter deep. Thus, while these latter potential adversaries are very real, they are somewhat more readily assessed and potentially easier with which to grapple. There are always exceptions, e.g., NTP’s $612M settlement with RIM, or the recent $501 million dollar award to Dr. Bruce Saffran, who had sued Boston Scientific for infringement of a single patent.

IN A CHANGING IP AND BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT, WHAT IS THE CORRECT IP STRATEGY?

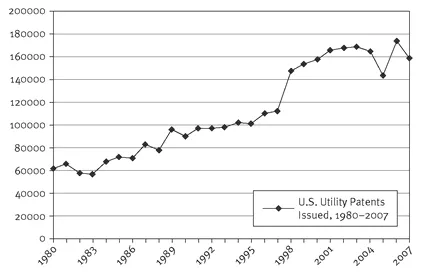

Until the emergence of patent trolls, the primary IP concern of CEOs of innovative companies was that their R&D, patenting activities, and overall investment in innovation was sufficient to produce an ample supply of intellectual property that would competitively differentiate the company’s products from competitors and thereby drive higher revenues. At the same time, they would provide an adequately broad and deep IP portfolio such that if anyone tried to poke a stick in the company’s marketing wheel, there were more than enough sticks available in the firm’s patent portfolio to stop most patent enforcement strikes from other product-producing companies. This philosophy led to an enormous increase in issued U.S. utility patents in the period from 1980-2007 as companies built a patent arsenal capable of “mutually assured destruction” (see Exhibit 1.2).

EXHIBIT 1.2 U.S. UTILITY PATENTS ISSUED, 1980-2007

By the early 1990s, as potential licensees were becoming more knowledgeable and sophisticated in the business and legal aspects of defending against patent aggression by others, the most experienced would-be licensors (such as IBM) had come to the conclusion that they needed to evolve their IP strategy to transform from “win-lose” (taxing those companies who used their inventions) to “win-win” (providing value to the licensee, rather than simply a patent license). One approach was to focus on the transfer of valuable and differentiating technology to the licensee (together with a patent license). Such a strategy provided that the licensor’s most talented engineers would teach engineers from the licensee how to adopt the licensed technology, thereby enabling the licensee to enter the market with products of improved performance and function sooner—and with less expense—than would have been possible without the transfer of the differentiating technology. The licensor received a higher royalty than they would have if they had licensed only patents without the know-how, and completed the transactions in less than a year, rather than the two to five years that would have been required to complete the average patent-only “win-lose” license.

While this strategy worked extremely well for the few companies that adopted it broadly, such as IBM, in more than 15 years it has failed to gain the level of acceptance it deserves....

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Also by Bruce Berman

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Acknowledgements

- About the Editor

- Introduction

- PART 1 - IP Business Models

- PART 2 - I P Performance

- PART 3 - IP Transactions

- Index