![]()

PART 1

Principles of Value Creation

1. Marketing and Shareholder Value

2. The Shareholder Value Approach

3. The Marketing Value Driver

4. The Growth Imperative

![]()

1

Marketing and Shareholder Value

‘If you are not willing to own a stock for 10 years don’t even think about it for 10 minutes.’

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report

INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

In recent years creating shareholder value has become the overarching goal for the chief executives of more and more major companies. As we shall see, both theoretically and empirically the case for managers choosing strategies that maximise shareholder value is almost unchallengeable. Those companies which have achieved this suggest that there should be no conflict between marketing and shareholder value.

The illusion of conflict has occurred because many managers have confused maximising shareholder value and maximising profitability. The two are completely different. Maximising profitability is short-term and invariably erodes a company’s long-term market competitiveness. It is about cutting costs and shedding assets to produce quick improvements in earnings. By neglecting new market opportunities and failing to invest, such strategies destroy rather than create economic value. Strategies aimed at maximising shareholder value are different. They focus on identifying growth opportunities and building competitive advantage. They punish short-term strategies that destroy assets and fail to capitalise on the company’s core capabilities.

By the time you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the new marketing challenges faced by today’s managers

• Understand the central role of shareholder value

• Assess why marketing has too little influence in the board room

• Recognise why marketing is the bedrock of shareholder value analysis

• Identify how the profession and discipline of marketing need to change to make it more relevant to top management

The next section discusses the striking new challenges of the information age: global markets, changing industrial structures, the information revolution and rising consumer expectations. It is shown how these changes have far-reaching implications for the strategies and organisations of all businesses. This leads to a discussion of the shareholder value concept and the market-to-book ratio as measures of the success of a business.

A major problem for marketing is that it has not been integrated with the modern concept of financial value creation. This has handicapped the ability of marketing managers to contribute to top management decision-making. Yet marketing-led growth is at the heart of value creation. Without effective marketing, the shareholder value concept becomes little more than another destructive technique gearing management to rationalisation and short-term profits. Value-based marketing is presented as a new approach, which integrates marketing directly into the process of creating value for shareholders and thereby for all stakeholders. Value-based marketing makes the shareholder concept more valuable and marketing more effective.

MANAGING IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The enormous changes in the global market environment explain today’s pressures for greater management effectiveness. Competitive capitalism is Darwinian in nature. Businesses succeed when they meet the wants of customers more effectively than their competitors. Corporate profitability depends primarily on the company’s ability to offer products and services which customers choose to pay for. But what products and services customers regard as attractive is a function of the market environment. What is an appealing computer, retail store or banking service today will not be tomorrow. Technological change, new competition and changing wants make yesterday’s solutions obsolete and create the opportunity for new answers.

The result is that most companies do not usually last very long. De Geus calculated that the average life expectancy of a Western company is well below 20 years.[1] The period over which a successful firm can maintain a profitable competitive advantage is usually even shorter. Normally any innovation in product, services or processes is quickly copied and the surplus profit is competed away. Even where a company endures and grows, its true profitability normally erodes. Studies show that the average company does not maintain a return above its cost of capital for more than seven or eight years.[2]

While the period over which the average business is successful is short, there are companies that do better. There are a few examples of companies that have survived and maintained successful economic performance over a much longer period. Currently examples would include GE, Coca-Cola, Nike and Hewlett-Packard. But quoting examples of excellent companies is a hazardous venture. Great companies have a tendency to go belly-up when the environment changes fundamentally. Few leaders have the perspicacity, courage or capabilities to overturn the strategies, systems and organisation which created their past achievement.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

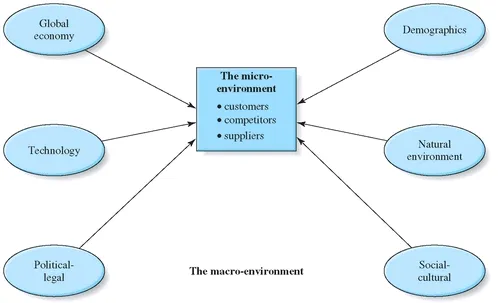

Environmental changes affecting the performance of the business can be categorised as macro or micro. Macroenvironmental changes are the broad outside forces affecting all markets. These include the major economic, demographic, political, technological and cultural developments taking place today. The microenvironment refers to the specific developments affecting the firm’s individual industry: its customers, competitors and suppliers. These developments reflect the impacts of the macroenvironmental changes on the specific industry (Figure 1.1).

Today this macroenvironment is experiencing unique historical changes which are fundamentally redrawing the business and social landscape. These changes have been given various names including the ‘post-industrial society’, the ‘global village’, the ‘third wave’ and perhaps most accurately the ‘information age’.

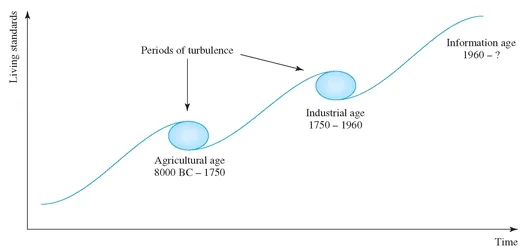

Social scientists describe three periods of economic evolution in the Western world: the agricultural era, which lasted from around 8000 BC to the mid-eighteenth century; the industrial era, which lasted until the late twentieth century; and finally what we will call the information age, which began in the 1960s and will last for decades to come.[3] These dates are of course approximate and overlapping. The first era was based on agriculture, with physical labour being the driver of any wealth that was achieved. This eventually gave way to the second era sparked by the industrial revolution, when machinery replaced muscle power, and factories replaced agriculture as the dominant employer, leading to an enormous growth in both agricultural and industrial productivity.

Figure 1.1 The Business Environment

While the agricultural era lasted for over two thousand years, the industrial age lasted only two hundred. The 1960s began to see the end of the industrial era and the beginning of the new information age. Employment in manufacturing began to drop in all the advanced countries and the service sector became the new focus for growth. Blue-collar workers who operated equipment in crowded factories were increasingly replaced by white-collar workers working individually or in small teams using computers and scientific knowledge in office environments. Today, information technology has replaced factories and machine power as the source of productivity growth and competitiveness.

The transitional periods between the three great waves of change have not been smooth. In Figure 1.2 each wave is represented by an ‘S’ curve that shows an early period of turbulence, followed by a long spell of maturity, and then its eventual demise as new technologies take over. The last decades of the twentieth century witnessed the period of turbulence marking the birth of the information age and the death of the industrial era. The turbulence included record levels of mergers and acquisitions, the collapse of communism in the former USSR and its satellites, and economic crises in South East Asia. All these reflected old second-wave industries and social organisations being pushed aside in the competitive environment of the new information age.

Four aspects in particular of the new information age require fundamental strategic and organisational responses from management:

1. The globalisation of markets

2. Changing industrial structures

3. The information revolution

4. Rising customer expectations

Figure 1.2 The Three Waves of Economic Change

THE GLOBALISATION OF MARKETS

The new information age has seen a dramatic shift to global markets and competition. Across more and more industries, firms that are not building global operations and marketing capabilities are losing out. Recent decades have seen an enormous growth of international trade in goods, services and capital. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor organisation the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been the means of negotiating a general lowering of barriers to trade between countries and an opening up of markets. The stimulus to this liberalisation of trade has been experience. Governments have seen, often painfully, that protecting home industries and markets from competition does not work. It only leads to higher inflation, lower economic growth and domestic companies lacking the levels of efficiency and entrepreneurial skills ever to be internationally competitive. Other stimuli to the globalisation of markets and competition have been faster and cheaper transportation and a continuing telecommunications revolution that has made global communications cheap, simple and effective. Finally, the barriers to participation in world trade have often come down dramatically. Today any business can open an Internet web site and market to customers from the other side of the world, just as easily as to its customers around the corner.

The result has been the emergence of new transnational companies organised to maximise the opportunities to be gained from the new global market-place and to minimise the costs of serving it. Companies like Microsoft, GE, Intel, Merck, IBM, Starbucks and McDonald’s are selling in all the key markets. Their supply chains are equally global, with materials and components sourced from the cheapest locations, assembly and logistics organised from the most effective regional bases, and research and development located where relevant knowledge is most accessible.

In most sectors, small domestically-orientated companies lack the economies of scale to remain competitive over the longer run. The scale economies of the transnational companies lie not so much in manufacturing costs but in information and knowledge. Focused transnationals like Intel, Apple, Dell and Cisco win out because they can afford to spend more on research and development, on building brands, on information technology and on marketing. Once new opportunities are identified they can also marshal the resources that are necessary to capitalise and develop the market.

CHANGING INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURES

The information age is changing the nature of the profit opportunities available to businesses. Many markets that were once at the very heart of the economy have ceased to offer profit opportunities for Western firms. Other new markets are rapidly emerging that offer enormous profit opportunities to companies that can move fast and decisively to capitalise on them.

Manufacturing industries can be divided into two types. One type comprises traditional industries such as textiles, coal mining, heavy chemicals, steel and auto manufacturing, which are relatively labour intensive and make heavy use of raw materials. These industries are relocating rapidly to the developing countries, which have a comparative cost advantage. Such industries also generally suffer the problem of substantial excess manufacturing capacity because these new countries have invested too aggressively in seeking to gain market shares. The result has been falling prices and very poor returns on investment.

The second type of industries are the information- and knowledge-based ones such as pharmaceuticals, communications equipment, electronics and computers, aerospace and b...