![]()

PART ONE

“HUMANITY IS OVERRATED”: HOUSE ON LIFE

![]()

1

SELFISH, BASE ANIMALS CRAWLI NG ACROSS THE EARTH: HOUSE AND THE MEANING OF LIFE

Henry Jacoby

We are selfish, base animals crawling across the Earth. Because we got brains, we try real hard, and we occasionally aspire to something that is less than pure evil.

—“One Day, One Room”

So says Gregory House. It doesn’t sound like he thinks life has any meaning, does it? Yet our Dr. House is leading what Socrates called “the examined life,” and what Aristotle called “a life of reason,” and such a life is a meaningful one. But how can this be? Could someone like House, who apparently thinks that life has no meaning, lead a meaningful life? And does House actually believe that our lives are meaningless?

“If You Talk to God, You’re Religious; If God Talks to You, You’re Psychotic”

Many people think that if there were no God, then life would have no meaning. So let’s start there. Let’s assume that our lives have meaning because we are fulfilling God’s plan. In this case, meaning is constituted by a certain relationship with a spiritual being. If God does not exist, then our lives are meaningless. Or even if God does exist, but we’re not related to Him in the right way, then again our lives are meaningless.

Perhaps God has a plan, and your life is meaningful to the extent that you help God realize that plan. For example, in the Kabbalah, the mystical writings of Judaism, we’re supposed to be helping God repair the universe. This is a good example of what I mean; we’re supposed to be helping God’s plan succeed. A person who does this by doing good deeds and the like is thereby leading a meaningful life. Notice that someone could, in this view, lead a meaningful life, even if he believed that life had no meaning. Such a person might be doing God’s work without realizing it. Could this be the sense in which House is leading a meaningful life?

Well, House doesn’t believe in God; that’s pretty clear. He consistently abuses those who do—for example, the Mormon doctor he calls “Big Love” in season four. In the season one episode “Damned If You Do,” the patient, Sister Augustine, is a hypochondriac. As another Sister explains to House that “Sister Augustine believes in things that aren’t real,” House quips, “I thought that was a job requirement for you people.” As another example, in “Family” House finds Foreman in the hospital chapel (Foreman is feeling remorse after having lost a patient), and he whispers, “You done talking to your imaginary friend? ’Cause I thought maybe you could do your job.”

House’s distaste for religion mostly stems from the lack of reason and logic behind religious belief. When Sister Augustine asks House, “Why is it so difficult for you to believe in God?” he says, “What I have difficulty with is the whole concept of belief; faith isn’t based on logic and experience.” A further example occurs in season four (“The Right Stuff ”) when “Big Love” agrees to participate in an experiment that may save a patient’s life. The experiment requires him to drink alcohol, which conflicts with his religious beliefs. He tells House that he was eventually persuaded by the reasoning behind House’s request. “You made a good argument,” he says. House is both impressed and surprised. “Rational arguments usually don’t work on religious people,” he says, “otherwise, there wouldn’t be any religious people.”

Reason, not faith, gets results in the real world. Again in “Damned If You Do,” House berates Sister Augustine when she refuses medical treatment, preferring to leave her life in God’s hands. “Are you trying to talk me out of my faith?” she asks. House responds: “You can have all the faith you want in spirits, and the afterlife, heaven and hell; but when it comes to this world, don’t be an idiot. Because you can tell me that you put your faith in God to get you through the day, but when it comes time to cross the road I know you look both ways.” Here House is hammering home the point that faith might provide comfort or make us feel good, but practical matters require reason and evidence.

Unlike many, House doesn’t find religious belief—specifically, the idea of an afterlife—all that comforting. At one point he says, “I find it more comforting to believe that this [life] isn’t simply a test” (“Three Stories”).

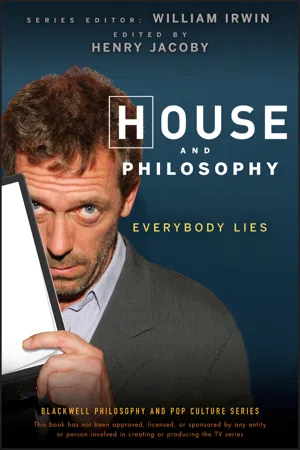

Even putting aside House’s views for the moment, there are serious problems with the idea that God dictates the meaning of our lives. Think of great scientists, who better our lives with their discoveries. Or humanitarians, who tirelessly work to improve the world. Or entertainers even—like Hugh Laurie!—who make our lives more enjoyable. Do we really want to say that if there’s no God, then these accomplishments and goods don’t count?

A further and fatal problem (first presented about a similar idea in Plato’s dialogue Euthyphro, from which I now shamelessly borrow) is this: What makes God’s plan meaningful in the first place? Is it meaningful simply because it’s God’s plan, or does God plan it because it’s meaningful? If it’s the former, then the plan is simply arbitrary. There’s no reason behind it, and therefore it could just as easily have been the opposite! But this doesn’t sit well. Surely not just any old thing could be meaningful.

Instead most would say God’s plan is as it is because God sees that such a course of events would be meaningful. But if this is right, then something else (besides God’s will) makes the plan meaningful. So the meaning in our lives has nothing to do with God. House is right about that (whether or not God exists).

Eternity, Anyone?

Perhaps just the fact that we have souls gives us intrinsic value and makes our lives meaningful. Or perhaps it has something to do with the idea that souls are supposed to be immortal and live on in an afterlife. If there is an afterlife, then this life is meaningful because it’s leading somewhere.

But House no more believes in the soul than he does in God; and he’s convinced there’s no afterlife as well. No evidence, right? What about so-called near-death experiences? Do they provide evidence for the afterlife?

In the season four episode “97 Seconds,” a patient tries to kill himself because he believes in the afterlife and wants to be there. He has already been clinically dead and brought back, and while “dead,” he had “experiences” in a beautiful, peaceful afterlife. He says, “The paramedics said I was technically dead for 97 seconds. It was the best 97 seconds of my life.” House, of course, won’t stand for any of this. He tells the patient: “Okay, here’s what happened. Your oxygen-deprived brain shutting down, flooded endorphins, serotonin, and gave you the visions.”

In the same episode the afterlife theme comes up again as a dying cancer patient refuses the treatment that would prolong his painful life. He prefers death, and tells House and Wilson, “I’ve been trapped in this useless body long enough. It’d be nice to finally get out.” House blasts back: “Get out and go where? You think you’re gonna sprout wings and start flying around with the other angels? Don’t be an idiot. There’s no after, there is just this.” Wilson and House then leave and have this wonderful exchange:

Wilson: You can’t let a dying man take solace in his beliefs?

House: His beliefs are stupid.

Wilson: Why can’t you just let him have his fairy tale if it gives him comfort to imagine beaches, and loved ones, and life outside a wheelchair?

House: There’s 72 virgins, too?

Wilson: It’s over. He’s got days, maybe hours left. What pain does it cause him if he spends that time with a peaceful smile? What sick pleasure do you get in making damn sure he’s filled with fear and dread?

House: He shouldn’t be making a decision based on a lie. Misery is better than nothing.

Wilson: You don’t know there’s nothing; you haven’t been there!

House: (rolls his eyes) Oh God, I’m tired of that argument. I don’t have to go to Detroit to know that it smells!

But House, ever the scientist, wants proof. He’s going to see for himself! He arranges to kill himself and is clinically dead for a short time before being brought back. At the end of the episode, he stands over the body of the patient, who has since died, and says, “I’m sorry to say . . . I told you so.” What would House have said if there were an afterlife and God called him to account? Probably, “You should have given more evidence.”1

Whether House’s little experiment proved anything or not, what should we say about meaning and eternity? House, the philosopher, disagrees with the sentiment that life has to be leading somewhere to give it meaning. Consider this exchange between House and his patient Eve, who was raped, in the brilliant episode “One Day, One Room”:

House: If you believe in eternity, then life is irrelevant—the same as a bug is irrelevant in comparison to the universe.

Eve: If you don’t believe in eternity, then what you do here is irrelevant.

House: Your acts here are all that matters.

Eve: Then nothing matters. There’s no ultimate consequences.

The patient expresses the idea that if this is all there is, then what’s the point? But for House, if this is all there is, then what we do here is the only thing that matters. In fact, it makes it matter all that much more.

“If Her DNA Was Off by One Percentage Point, She’d Be a Dolphin”

Maybe our lives have no meaning. Maybe we are just crawling across the Earth, and nothing more. Someone could arrive at this conclusion two different ways. First, if meaning depends on God, the soul, or the afterlife, and none of these is real, then the conclusion follows. But also, if our lives are eternal, then, as House says, what we do in this limited time on Earth is diminished to the point of insignificance. From the point of view of an infinite universe, moreover, how can our little scurryings about amount to much of anything?

Philosophers who think that life is meaningless are called nihilists. To avoid nihilism, it seems we should stop worrying about God and the afterlife—and House, remember, rejects these anyway—and instead try to find meaning in our finite lives in the natural world. As House says, “Our actions here are all that matters.”

How about how we feel about our actions? Does that matter? If a person feels that she’s not accomplishing her goals, for example, or not having a positive impact on society, she might feel that her life has little or no meaning. But if she feels good about what she’s doing, if it matters to her, might we not say that she’s leading a meaningful life?

No, this is too easy. A person might be getting everything he wants, but if those wants are trivial, irrational, or evil, then it’s hard to see this adding up to a meaningful life. For example, imagine someone like House who only watched soaps and played video games, but was not also a brilliant diagnostician busy saving lives. That would be a life without much meaning, even though our non-doctor version of House here might be perfectly content with his life.

Not only does “meaningful” not equal “getting what you want,” but “meaningless” isn’t the same as “not getting what you want.” We might again imagine someone like House or even the real House himself: a terrific doctor helping a lot of people and saving lives, yet miserable, and not getting what he wants out of life at all. Yet, his life would still be meaningful and important because of its accomplishments, even though it didn’t “feel” that way to him.

Now what if you care about things that are not trivial, irrational, or evil? Then, perhaps, your life could be meaningful to you—subjectively, as philosophers say—and at the same time be meaningful in the world, apart from your feelings, or objectively . So the question becomes this: What sort of life can we lead that produces meaning in both of these senses? And is our Dr. House leading such a life?

“You Could Think I’m Wrong, but That’s No Reason to Stop Thinking”

Socrates (469-399 BCE), the first great hero of Western philosophy, was found guilty of corrupting the youth of Athens and not believing in the gods. For his crimes he was condemned to death. In actuality, Socrates was being punished for his habit of questioning others and exposing their ignorance in his search for truth. The jury would’ve been happy just to have him leave Athens, but Socrates declined that possibility, because he knew that his way of life would continue wherever he was.

Well, why not just change, then? In Plato’s dialogue Apology, which describes the trial of Socrates, we hear Socrates utter the famous phrase “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates was telling us that he would rather die than give up his lifestyle. Why? What is an examined life anyway?

An examined life is one in which you seek the truth. You are curious. You want to understand. You do not just accept ideas because they are popular or traditional; you are not afraid to ask questions. This is the life of the philosopher.

The great British philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) described the value of this lifestyle and the value of philosophy in general when he wrote:

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation.2

Surely House agrees with this. In the episode “Resignation” House finally figures out what’s killing a young girl, and he tries to tell her. Since this information wil...