eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1

Cognition, Biology, and Methods

Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton, Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1

Cognition, Biology, and Methods

Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton, Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the past fifty years, scholars of human development have been moving from studying change in humans within sharply defined periods, to seeing many more of these phenomenon as more profitably studied over time and in relation to other processes. The Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1: Cognition, Biology, and Methods presents the study of human development conducted by the best scholars in the 21st century. Social workers, counselors and public health workers will receive coverage of of the biological and cognitive aspects of human change across the lifespan.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1 by Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton, Richard M. Lerner, Willis F. Overton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Psicología del desarrollo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Life-Span Development

Concepts and Issues

LIFE-SPAN DEVELOPMENT: CONCEPTS AND ISSUES

A Handbook of Life-Span Development would seem to merit some serious discussion of the meaning of life-span development. Life-span development is a phrase that has been a prominent feature of developmental psychology and developmental science since the early 1970s, but few attempts have been made to conceptually clarify its core meaning(s). One could, of course, take the classic empiricist approach and argue that the work of conceptual clarification is quite meaningless—perhaps producing more heat than light—and the phrase is sufficiently defined operationally by the chapters that the reader encounters in the two volumes of this handbook, together with all other volumes of text that in the past have included the phrase life-span development. The advantage of this radically empirical and radically pragmatic approach—life-span development is what life-span developmental researchers do—is that it allows us to glide over possible fissures and tensions that might be present in the study of development across the life span, thus offering the broadest of possible umbrellas under which research fortuitously might flourish. On the other hand, such an approach seems somewhat akin to dropping a group of people into a dark forest and telling them to walk out. If they did enough walking, they might succeed, but they also might forever walk in circles. Some kind of additional directions would be helpful.

I express my appreciation to all of the authors in this volume for their tireless work and creative efforts and for their putting up with my obsessions as an editor, but most of all for teaching me so much about life-span development. I send a special note of appreciation to those who entered into a conversation with me about the shape and breadth of life-span development, and those who helped through editorial suggestions and feedback on this introductory chapter, including Ellen Bialystok, Fergus Craik, Jeremy Carpendale, Rich Lerner, Leah Light, Ulrich Müller, John Nesselroade, K Warner Schaie, and Hayne Reese. I must also single out two people for an additional acknowledgment: first, to Rich Lerner, for his constant and unwavering friendship and support over many years, for inviting me to edit this volume, and for his help in numerous ways throughout the process; and second, to Hayne Reese, for his friendship and support over even more years, as well as for being the person who introduced me to life-span development by inviting me to write a paper with him for the very first Life-Span Development Conference at West Virginia University in 1969. That paper—our first of many dialectical collaborations—later became a chapter in the first volume of the life-span development series: Reese, H. W., & Overton, W. F. (1970). Models of development and theories of development. In L. R. Goulet & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Research and theory (pp. 115-145). New York: Academic Press. How different my life would have been had we never met.

This chapter focuses on conceptual clarifications—providing some direction—designed to avoid confusion and facilitate progress toward the goal of enhancing our knowledge and understanding of “life-span development.” It is recognized that the directions suggested here may have to be supplemented by finer details, and also that there may be other successful paths. However, the chapter is partially designed to undercut philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s acerbic remark when he maintained that “in psychology there are empirical methods and conceptual confusions” (1958, p. xiv), and partially it is designed in acknowledgment of Robert Hogan’s comment that “all the empiricism in the world can’t salvage a bad idea” (2001, p. 27); but most broadly, it is designed in the hopes of producing more light than heat and providing at least some suggestions for pathways in moving forward in the field of life-span development.

The second section of the chapter, The Concept of Development, explores various meanings of the general concept of “development.” These meanings have, at times, been taken as competing alternatives, and here a proposal is made that formulates a more inclusive integrative understanding of the area that defines the core of life-span development. Because formulating an integrative understanding requires the application of some principles of integration, the following section, Relational Metatheory, presents “relationism” as a broad-principled method designed to achieve this goal. As a set of principles, relationism is also used to explore other concepts that are central to a lifespan approach to development. It will become obvious early in the chapter that “system” plays a central role in the definition and exploration of development. The third section of the chapter, Relational Developmental Systems, discusses “system” and system approaches to the study of development. In this section, various system concepts, such as “closed and open systems,” “complex systems,” “adaptive systems,” and especially “relational developmental systems,” are examined. In turn, the notion of relational developmental systems operates as the grounding for the fourth and final substantive section of the chapter, Age, Life-Span Development, and Aging, which focuses on the “life-span” nature of life-span development. In this section, considerations of “adult development,” “age,” “aging,” “time,” “description,” and “processes” establish the context for a relational (see Relational Metatheory), developmental (see Concept of Development), systems (see Relational Developmental Systems) proposal that integrates life-span development, adult development, and aging within a single-process, dual-trajectory understanding of life-span development.

In entering this conceptual arena of inquiry, a few introductory words are needed concerning a distinction that will be central to the exploration of life-span development. This is the distinction between metatheory, theory, and methods. In the heydays of neopositivism, or radical empiricism, theory and method lost their status as two distinguishable but interdependent spheres of science, and in radical empiricism’s insistence on monistic materialist solutions, theory became squeezed down into method. A consequence, which has lasted even into the present, is that “theory” came often to designate merely the empirical interrelations among the various antecedent variables associated with outcome or dependent variables. So, for example, when asked about a theory or model of aggression, one could, and often still can, point to a structural equation diagram and show—with lines, arrows, and circles—the correlations and weightings among associated variables and aggression outcomes. Today in a postpositivist scientific world, these concepts of theory and method again need to be differentiated: theory constitutes the distinguishable means of conceptual exploration in any designated area of enquiry; methods are the distinguishable means of observational exploration of that area; and they are differentiated and relationally joined spheres that are necessary coactors in scientific enquiry. To paraphrase Immanuel Kant, theories without methods are empty speculations; methods without theories are meaningless data. This brings us to the notion of “metatheory.”

With the emergence of postpositivist science developed in the works of Steven Toulmin (1953), N. R. Hanson (1958), Thomas Kuhn (1962), Imre Lakatos (1978), and Larry Laudan (1977), among others, it became clear that any viable scientific research program entails a set of core assumptions that frame and contextualize both theory and methods. These core, often implicit, assumptions have come to be called metatheoretical, and their primary function is to provide a rich source of concepts out of which theories and methods emerge. Metatheories transcend (i.e., “meta”) theories and methods in the sense that they define the context in which theoretical concepts and specific methods are constructed. A metatheory is a set of interlocking rules, principles, or stories (narrative) that both describes and prescribes what is acceptable and unacceptable as theoretical concepts and as methodological procedures. For example, one metatheory may prescribe that no “mental” concepts (e.g., “mind”) may enter theory, and that all change must be understood as strictly additive (i.e., no emergence, no gaps, strict continuity), and hence will be measured by additive statistical techniques. This is a description of some features of early behaviorism. Another metatheory may prescribe that mind is an essential feature of the system under consideration, that the system operates holistically, that novel features emerge, and that nonadditive statistical techniques are a welcome feature of any methodological toolbox. This is a description of some metatheoretical features of what is termed a “relational developmental systems approach,” which is described in detail later in the chapter. Metatheoretical assumptions also serve as guidelines that help to avoid conceptual confusions. Take, for example, the word stage. In a metatheory that allows discontinuity of change and emergence, “stage” will be a theoretical concept referring to a particular level of organization of the system; in a metatheory that allows only continuity, if “stage” is used at all—it will be a simple descriptive summary statement of a group of behaviors (e.g., the stage of adolescence), but never as a theoretical concept.

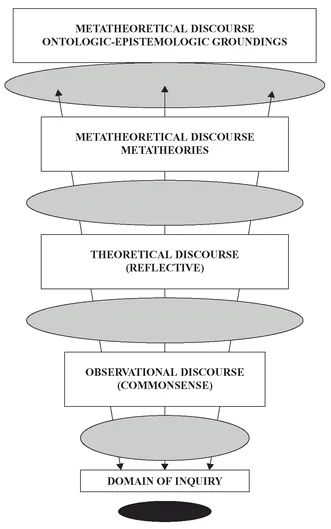

Together with metatheory, theory, and method, it needs to be kept in mind that concepts can and do operate at different levels of discourse (see Figure 1.1). Theories and methods refer directly to the empirical world, whereas metatheories refer to the theories and methods themselves. The most concrete and circumscribed level of discourse is the observational level. This is one’s current commonsense level of conceptualizing the nature of objects and events in the world. For example, one does not need a professional degree to describe a child as “warm” “loving,” “distant,” “angry,” “bright,” or even “attached,” “aggressive,” or “depressed.” This observational, commonsense, or folk level of analysis has a sense of immediacy and concreteness, but when reflected on, it is often unclear, muddy, and ambiguous. It is the reflection on folk understanding that moves the level of discourse to a reflective level, which is the beginning of theoretical discourse. Here, reflection is about organizing, refining, and reformulating observational understandings in a broader, more coherent, and more abstract field. At the theoretical reflective level, concepts are about the observational level, and these range from informal hunches and hypotheses to highly refined theories about the nature of things, including human behavior and change. Relatively refined theories may themselves be narrow or broad. For example, some theories of memory are relatively narrow, whereas Demetriou and colleagues (Chapter 10 of this volume) present a theory of the architecture of mind that is very broad. Similarly, the theories of Piaget, Vygotsky, Erikson, and Werner are grand theories—theories designed to explain a broad sweep of the development of psychological functioning—whereas Bowlby’s theory more narrowly focuses on attachment and its development.

Figure 1.1 Levels of discourse.

The metatheoretical level itself operates above, and functions as a grounding for, the theoretical level. At the metatheoretical level, reflective thought is about basic concepts that, as mentioned earlier, form the contextual frame for the theoretical and observational levels. And here, to make matters a bit more complicated, it is further possible to discriminate levels of metatheory. Thus, arguably, theories such as “relational developmental systems,” “dynamical systems,” “embodiment,” “action,” and even “information processing,” and “behaviorism” actually constitute metatheories that frame specific theories. These metatheories are each grounded in a coherent sets of broader metatheoretical principles. And these, in turn, are grounded at the final apex of the levels of discourse; in those coherent sets of universal ontological and epistemological propositions termed worldviews, including at least the classic “mechanistic,” “contextualist,” “organicist,” and a more recent set, representing the synthesis of contextualism and organicism, termed “relationism.”

If all of this abstract talk of levels of discourse and metatheories seems too abstract for pragmatic minds, it should be remembered that most of the fundamental issues in psychology originated in abstract concepts, and it is at that level, and only at that level, that they can begin to be resolved. Of course, one can throw away all abstract maps and yielding to the pragmatic urge, just start walking in the forest; but again, although that may get us out of the woods, it may also just keep us wandering in circles.

THE CONCEPT OF DEVELOPMENT

With metatheories, theories, methods, and levels of discourse as background, we can embark on an exploration of life-span development. At first blush it would seem that the “life-span” portion is simple enough: life-span development is the study of the development of living organisms from conception to the end of life. This is a satisfactory initial working definition of life span, but later discussions (especially in the final section of the chapter, Age, Life-Span Development, and Aging) point to some rather thorny conceptual and practical issues presented by such a definition of life span. But from this starting point we can say that the field of life-span development entails the scientific study of systematic intraindividual changes—from conception to the end of life—of an organism’s behavior, and of the systems and processes underlying those changes and that behavior. The field encompasses the study of several categories of change such as ontogenesis (development of the individual across the life span), embryogenesis (development of the embryo), orthogenesis (normal development), pathogenesis (development of psychopathology), and microgenesis (development on a very small time scale such as development of a single percept). But the field is also comparative and thus includes the study of phylogenesis and evolution (development of the species), as well as historical and cultural development. Human ontogenesis/orthogenesis is the most familiar focus of attention of life-span development, and within this series a number of age-related areas of study exist—infancy, toddlerhood, childhood, adolescence, early adult, mature adult, and late adulthood. Both within and across areas, life-span developmental scientists explore biological, cognitive, emotional, social, motivational, and personality dimensions of individual development. The field also maintains a strong research focus on contextual ecological systems that impact on development including the family, home, neighborhoods, schools, and peers, and on interindividual differences.

Organization, Sequence, Direction, Epigenesis, and Relative Permanence

Individual change constitutes the fundamental defining feature of development, but it is important to immediately emphasize that not all change is necessarily developmental change. Developmental change entails five necessary defining features: (1) organization of processes (also termed structure and system), (2) order and sequence, (3) direction, (4) epigenesis and emergence, and (5) relative permanence and irreversibility. These features frame two broad forms of change that traditionally have been considered developmental, but have also at times been considered competing alternative definitions of developmental change—transformational change and variational change.

Understanding the place of transformational and variational change in development requires a type-token distinction, which is also a distinction between structure and content. Perception, thinking, memory, language, affect, motivation, and consciousness are universal psychological processes (types), characteristic of the human species as a whole. Any given percept, concept, thought, word, memory, emotion, and motive represents a particular expression of a universal process (tokens). Although each form of change is entailed by any behavioral act, transformational change primarily concerns the acquisition, maintenance, retention, or decline of universal processes or operations (types), whereas variational change primarily concerns the acquisition, maintenance, retention, or decline o...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contributors

- CHAPTER 1 - Life-Span Development

- CHAPTER 2 - Emphasizing Intraindividual Variability in the Study of Development ...

- CHAPTER 3 - What Life-Span Data Do We Really Need?

- CHAPTER 4 - Brain Development

- CHAPTER 5 - Biology, Evolution, and Psychological Development

- CHAPTER 6 - The Dynamic Development of Thinking, Feeling, and Acting over the ...

- CHAPTER 7 - Structure and Process in Life-Span Cognitive Development

- CHAPTER 8 - Fluid Cognitive Abilities and General Intelligence

- CHAPTER 9 - Memory Development across the Life Span

- CHAPTER 10 - The Development of Mental Processing

- CHAPTER 11 - The Development of Representation and Concepts

- CHAPTER 12 - Development of Deductive Reasoning across the Life Span

- CHAPTER 13 - Development of Executive Function across the Life Span

- CHAPTER 14 - Language Development

- CHAPTER 15 - Self-Regulation

- CHAPTER 16 - The Development of Morality

- CHAPTER 17 - The Development of Social Understanding

- CHAPTER 18 - The Emergence of Consciousness and Its Role in Human Development

- CHAPTER 19 - The Development of Knowing

- CHAPTER 20 - Spatial Development

- CHAPTER 21 - Gesturing across the Life Span

- CHAPTER 22 - Developmental Psychopathology—Self, Embodiment, Meaning

- CHAPTER 23 - The Meaning of Wisdom and Its Development Throughout Life

- CHAPTER 24 - Thriving across the Life Span

- THE HANDBOOK OF LIFE-SPAN DEVELOPMENT:

- Author Index

- Subject Index