- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Internal Audit: Efficiency Through Automation teaches state-of-the-art computer-aided audit techniques, with practical guidelines on how to get much needed data, overcome organizational roadblocks, build data analysis skills, as well as address Continuous Auditing issues. Chapter 1 CAATTs History, Chapter 2 Audit Technology, Chapter 3 Continuous Auditing, Chapter 4 CAATTs Benefits and Opportunities, Chapter 5 CAATTs for Broader Scoped Audits, Chapter 6 Data Access and Testing, Chapter 7 Developing CAATT Capabilities, Chapter 8 Challenges for Audit,

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

CAATTs History

Computers are not new to us. From microwave ovens to DVDs, everywhere around us we see and feel the effect of the microchip. But, too often, we have either not applied these new technologies to our everyday work activities, or we have only succeeded in automating the functions we used to do manually. “Things are working fine the way they are” or “I’m not an IS auditor” are just two of the many excuses we hear for not capitalizing on the power of the computer. However, we cannot afford to ignore the productivity gains that can be achieved through the proper use of information technology. The use of automation in the audit function—whether it is for the administration of the audit organization or tools employed during the conduct of comprehensive audits—has become a requirement, not a luxury. In today’s technologically complex world, where change is commonplace, auditors can no longer rely on manual techniques, even if they are tried and true. Auditors must move forward with the technology, as intelligent users of the new tools. The vision of the auditor, sleeves rolled up, calculator in hand, poring over mountains of paper, is no longer a realistic picture. Automation has found its way into our homes, schools, and the workplace—now is the time to welcome it into the audit organization.

This book discusses microcomputer-based audit software, but the techniques and concepts are equally applicable to mainframe and minicomputer environments. Examples of software packages are provided, but the focus is on the discussion of an approach to using automation to assist in performing various audit tasks rather than the identification of specific audit software packages.

Throughout this book, Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATTs) and audit automation are meant to include the use of any computerized tool or technique that increases the efficiency and effectiveness of the audit function. These include tools ranging from basic word processing to expert systems, and techniques as simple as listing the data to matching files on multiple key fields.

The chapters:

• Define audit software tools

• Introduce relevant data processing concepts

• Discuss the implementation and benefits of information technology in auditing

• Describe the issues of data access, support to the audit function, and information technology training

This book was written as a guide to auditors who are interested in improving the effectiveness of their individual audits or the complete audit function through the application of computer-based audit tools and techniques. It does not cover technology audits, the audit of computer systems, or systems under development. However, the ideas and concepts are valid for IS auditors and non-IS auditors alike. The topics presented are particularly relevant to:

• Auditors with a requirement to access and use data from client systems in support of comprehensive or operational audits

• Audit managers looking for ways to capitalize on the potential productivity increases available through the adoption and use of CAATTs in the administration of the audit organization and in audit planning and conduct

• IS auditors wishing to expand their knowledge of newer tools and approaches, particularly in the microcomputer environment

• Persons with responsibility to implement automated tools and techniques within their operations

This book is designed to lead auditors through the steps that will allow them to embrace audit automation. It is written to help the audit manager improve the functioning of the audit organization by illustrating ways to improve the planning and management of audits. It is also written with the individual auditor in mind by presenting case studies on how automation can be used in a variety of settings.

It is hoped that this book will encourage auditors to look at audit objectives with a view to utilizing computer-assisted techniques. More than ever, auditors must increase their capability to make a contribution to the organization. The computer provides tools to help auditors critically examine information to arrive at meaningful and value-added recommendations.

The New Audit Environment

These are exciting times for internal auditors, especially those who see themselves as agents of change within their organization. The drive to do more with less, to do the right thing, or to reengineer the organization and the way it does business is creating an environment of introspection and change. Change is occurring at a faster rate than ever, and this change is being driven by technological advances. Companies wishing to survive in these times must strive to exploit new technologies in order to achieve a competitive advantage. Today’s business environment is rapidly and constantly changing, and technology is one of the key factors that are forcing auditors to reassess their approach to auditing. Other factors are the evolving regulations and audit standards calling for auditors to make better use of technology. These forces are creating a new audit environment, and audit professionals who understand how to evaluate and use the potential of emerging technologies can be invaluable to their organizations. New possibilities exist for auditors who can tie software tools into their organizations’ existing systems (Baker [2005]).

The Age of Information Technology

In the last 20 years, we have progressed from Electronic Data Processing (EDP) to Enterprise-wide Information Management (EIM). We have gone from a time when hardware drove the programming logic and the software selection to a time when the knowledge requirements are driving business activities. As little as 15 years ago, information was almost a mere by-product of the technology; the selected hardware platform determined the software, which would likewise be a determining factor of each application. Today, the technology, the hardware and software, are merely delivery mechanisms, not the determining factors behind either information technology purchases or systems development activities. One of the main tenets of EIM is that the information is a key resource to be managed and used effectively by every successful organization. Data holdings are driving business processes, not the reverse, and there has been an increased treatment of information as a strategic resource of the business. From an audit perspective, this means that data and information are equally important. First, to analyze the current state of the business critically; and second, to help determine where the business is going or should go.

Decentralization of Technology

We are seeing a greater reliance on computers in every aspect of our world. Data processing is no longer confined to programmers or to the mainframe systems. We have seen the emergence of enterprise-wide systems in all business/operational areas in many organizations. In some, the separate information processing by specialized applications is a thing of the past. Enterprise-wide systems are changing the notion of traditionally centralized data and applications. Application programmers have been transferred to business areas to support and encourage use of enterprise technology. Today, one can find business applications where a purchase order transaction is initiated in England, modified in the United States, and then sent to a processing plant in Mexico. All of this occurs in minutes—or even seconds—across time zones and continents. The modules or components are fully integrated with the business processes and occur without a paper trail. These types of applications make traditional manual audit approaches useless and impossible to apply. Auditors must learn how to access and analyze electronic information sources if they want to make a meaningful contribution to their organizations’ bottom line.

Absence of the Paper Trail

While a “less paper” rather than a “paperless” office is the best we may be able to achieve in the near future, we have already seen the disappearance of paper in many areas as a result of information systems and technology such as enterprise system, Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), Electronic Commerce (EC), and Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT). The audit trail is electronic and is therefore no longer visible and more difficult to trace. The volume of data and its complexity is increasing at a rapid rate because of the requirement to quickly focus company resources on emerging problems or potential opportunities. To some, this lack of transparency is a problem; to the more enlightened auditor, this is an opportunity.

Do More with Less

There is increasing pressure to do more with less. Over the last 200 years, most of the productivity gains have occurred within the areas of production, inventory, and distribution, but little gain has occurred within the administrative functions. The automation of production plants saw reductions in the number of production workers within a plant, going from 200 people on the assembly line with five managers to 50 people on the assembly line and five managers. With productivity increases in the traditional, blue-collar areas becoming harder to achieve, there is increasing pressure to make improvements in the white-collar areas. Reducing overhead, doing more with less, and rightsizing all circumscribe efforts to make productivity gains in the management areas of administration. Given the unfortunately still widely held view that audit is overhead, internal audit must not only become more efficient in delivering its products and services but often must also pay its own way and become more effective in order to succeed.

As might well be expected, the factors driving business organizations also drive the audit function. In order to better serve the increasingly complex needs of their clients, auditors must provide a better service, while being increasingly aware of the costs. To this end, auditors are looking for computer-based tools and techniques.

Definition of CAATTs

Many audit organizations have looked to the microcomputer as the new audit tool, a tool that can be used not only by IS auditors, but by all auditors. This book highlights the benefits of Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATTs) and outlines a methodology for developing and using CAATTs in the audit organization. Today’s auditors must become more highly trained, with new skills and areas of expertise in order to be more useful and productive. Increasingly, auditors will be required to use computer-assisted techniques to audit electronic transactions and application controls. Laws like the U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 are pushing audit departments to find new ways to link specialty tools into the complex business systems (Baker [2005]). By harnessing the power of the computer, auditors can improve their ability to critically review data and information and manage their own activities more rationally. Due to the critical shortage of these skills and talents, they will become even more valuable and marketable.

CAATTs are defined as computer-based tools and techniques that permit auditors to increase their personal productivity as well as that of the audit function. CAATTs can significantly improve audit effectiveness and efficiency during the planning, conduct, reporting, and follow-up phases of the audit, as well as improving the overall management of the audit function. In many cases, the use of the computer can enable auditors to perform tasks that would be impossible or extremely time-consuming to perform manually. The computer is the ideal tool for sorting, searching, matching, and performing various types of tests and mathematical calculations on data. Automated tools can also remove the restrictions of following rigid manual audit programs as a series of steps that must be performed. CAATTs allow auditors to probe data and information interactively and to react immediately to the findings by modifying and enhancing the initial audit approach.

In today’s age of automated information and decentralized decision-making, auditors have little choice concerning whether or not to make use of computer-based tools and techniques. It is more a question of whether the use of CAATTs will be sufficiently effective, and whether implementation will be managed and rationally controlled or remain merely haphazard. Many organizations have tried to implement CAATTs but have failed. By understanding the proper use and power of computer-based tools and techniques, auditors can perform their function more effectively. This understanding begins with knowledge of CAATTs, including their beginnings, current and potential uses, and limitations and pitfalls.

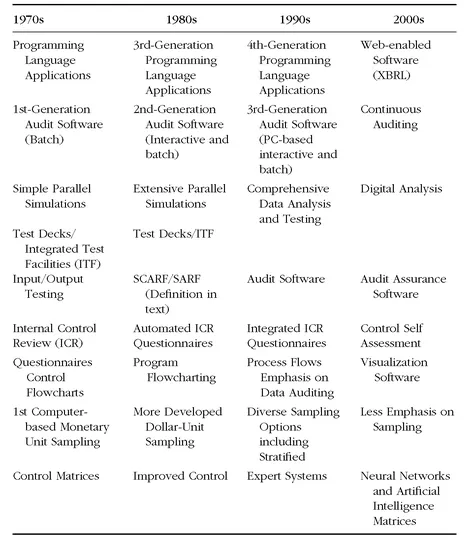

Evolution of CAATTs

Today’s microcomputer-based audit tools and techniques have their roots in mainframe Computer Assisted Audit Tools (CAATs), which in turn are surprisingly rooted in manual audit tools and techniques. These mainframe-based tools were primarily used to verify whether or not the controls for an application or computer system were working as intended. In the 1970s, a second type of CAAT evolved, which sought to improve the functionality and efficiency of the individual auditor. These CAATs provided auditors with the capability to extract and analyze data in order to conduct audits of organizational entities rather than simply review the controls of an application. A third type of CAAT, and a more recent use of automated audit tools, focuses on the audit function and consists of tools and techniques aimed at improving the effectiveness of the audit organization as a whole. But, for a moment, let’s step back in time to the late 1970s, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.1.

Books written on computer controls and audit in the 1970s did not include sections on end user computing or, at best, mentioned audit software only in passing. In fact, for the most part, auditors avoided dealing with the computer and treated it as the black box. Audit methodologies discussed the input and output controls, but largely ignored the processing controls of the system. The methodology employed was one of auditing around the computer. The main audit tools included questionnaires, control flowcharts, and application control matrices. Audit software was specifically written in general-purpose programming languages, was used primarily to verify controls, and parallel simulation was only beginning to gain ground. Audit software packages were considered as specialized programming languages to meet the needs of the auditor and required a great deal of programming expertise. The packages were mainframe-family dependent and consequently were limited in data access flexibility and completely batch-oriented.

By the 1980s, some of the more commonly used tools to verify an application system were test decks, Integrated Test Facilities (ITF), System Control Audit Review File (SCARF), and Sample Audit Review File (SARF) (Mair, Wood, and Davis [1978]). Other techniques included parallel simulations, reasonableness tests and exception reports, and systematic transaction samples. Some organizations were still achieving very effective results with these types of audit tools in the 1990s. In fact, according to a 1991 Institute of Internal Auditors’ Systems Auditability and Control (SAC) study, 22 percent of the respondents were still using test decks, 11 percent were still using ITF, and 11 percent were still using embedded audit modules (Institute of Internal Auditor’s Research Foundation [1991]).

EXHIBIT 1.1 Audit Tools and Techniques (Computer System Audit)

Audit Software Developments

The first audit software package, the Auditape System, which implemented Stringer’s audit sampling plan (Tucker [1994]), already provided limited capabilities for parallel simulation. The system facilitated limited recomputation of data processing results based on only a few data fields. In response to the Auditape System, many accounting, auditing, and software firms developed audit software packages that supported parallel simulation within computer families and against limited file and data types.

This proliferation of audit software and the overwhelming variety of data and file types to be audited led to the design of a generalize...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- About The Institute of Internal Auditors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- CHAPTER 1 - CAATTs History

- CHAPTER 2 - Audit Technology

- CHAPTER 3 - CAATTs Benefits and Opportunities

- CHAPTER 4 - CAATTs for Broader-Scoped Audits

- CHAPTER 5 - Data Access and Testing

- CHAPTER 6 - Developing CAATT Capabilities

- CHAPTER 7 - Challenges for Audit

- Appendices

- APPENDIX A - The Internet—An Audit Tool

- APPENDIX B - Information Support Analysis and Monitoring (ISAM) Section

- APPENDIX C - Information Management Concepts

- APPENDIX D - Audit Software Evaluation Criteria

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Internal Audit by David Coderre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Auditing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.