![]()

Part I: Beginnings and Religion

Chapter 1 (Vail) considers chocolate use by Mayan cultures in the pre-Hispanic Yucatán Peninsula, as evidenced through cacao-and chocolate-associated texts and information from actual residues of chocolate beverages discovered in ceremonial pots excavated at archaeological sites. Her chapter traces the role of cacao in Mayan religion and explores its function both as food and as a ceremonial item. Chapter 2 (Macri) examines theories on the origins of the word cacao (originally given as kakaw) and traces the scholarly debates regarding the linguistic origins of cacao and how the word diffused throughout Mesoamerica. Her chapter also reviews the controversial suggestion that first use of the word chocola-tl in the Nahua/Aztec language appeared only after the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the 1520s. Chapter 3 (Grivetti and Cabezon) identifies the several Mayan, Mixeca/Aztec, and contemporary Native American religious texts that report how the first cacao tree was given to humans by the gods. Their chapter considers how chocolate found a niche within Catholic ritual and social uses during religious holidays in New Spain/Mexico. Chapter 4 (Cabezon and Grivetti) translates and comments on a suite of extraordinary New World, Spanish texts written during that tragic period known as the Inquisition. The documents reveal how chocolate sometimes was associated with behaviors considered by the Church at this time to be heretical, among them blasphemy, extortion, seduction, and witchcraft, as well as accusations and denouncement for being observant Jews. Their chapter casts bright light on these dark actions practiced during this terrible period of Mesoamerican history. Chapter 5 (Shapiro) documents the intriguing and rich history of Jewish merchants influential in the 18th century cacao trade between the Caribbean islands of Aruba and Cura ç ao, New Amsterdam/New York, and elsewhere in New England. Her chapter reveals and describes for the first time the important role played by Jewish merchants who developed and expanded cacao trade in North America.

![]()

CHAPTER 1: Cacao Use in Yucatán Among the Pre-Hispanic Maya

Gabrielle Vail

Introduction

Much of the discussion of cacao in ancient Mesoamerica centers on Classic Maya culture, especially the period between 500 and 800 CE, because of the abundance of ceramics that reference cacao (kakaw) in their texts, and painted scenes that depict its use. Chemical analyses of residues from the bottoms of Classic period vessels reveal that cacao was an ingredient of several different drinks and gruels and that it was served in a wide variety of vessel types. The best known of these is the lidded vessel from Río Azul (Fig. 1.1), where the chemical signature of cacao was first identified by scientists from Hershey Corporation in 1990 [1, 2].1

Cacao played an important role in the economic, ritual, and political life of the pre-Hispanic Maya, and it continues to be significant to many contemporary Maya communities [3–5]. The different drinks and foods containing cacao that were served are described in hieroglyphic texts [6–9], the most common being a frothy drink that is depicted in scenes showing life in royal courts and as a beverage consumed by couples being married (Fig. 1.2).2 Field work among contemporary Maya groups suggests that it continues to be used as part of marriage rituals in some areas, where it is most commonly given as a gift—in either seed or beverage form—from the family of the prospective bridegroom to the bride’s family [11– 13].3 Cacao also represents an important offering in other ritual contexts, including those of an agricultural nature [15–17].

During the pre-Hispanic period, cacao seeds (also called “beans”) served as a unit of currency, and they were an important item of tribute [18, 19]. Because the tree can only be grown in certain regions (those that are especially humid), the seeds had to be imported to various parts of the Maya area that were not productive for growing cacao. It was considered one of the most important trade items, along with items like jade beads and feathers from the quetzal bird, which were worn by rulers to adorn their headdresses and capes.4

Cacao consumption was not important in and of itself but rather as part of elite feasting rituals that cemented social and political alliances. In addition to being one of the chief components of the feasts, cacao was one of the items gifted to those participating in the ritual, as were the delicate vases with their finely painted scenes of court life from which the beverage was consumed [20]. The scientific name of cacao, Theobroma cacao, meaning “food of the gods,” is an apt description of the role it played within ancient Maya culture.

Cacao use in the Maya area can be traced back to somewhere between 600 and 400 BCE, based on chemical remains recovered from spouted vessels from Belize [21, 22].5 But it has a much longer history that extends back, according to Maya beliefs, to the time before humans were created. In the creation story recorded in the text known as the Popol Vuh,6 cacao is one of the precious substances that is released from “Sustenance Mountain” (called Paxil in the Popol Vuh, meaning “broken, split, cleft”), along with maize (corn), from which humans are made, at the time just prior to the fourth or present creation of the world [29].7 Before this, it belonged to the realm of the Underworld lords, where it grew from the body of the sacri ficed god of maize, who was defeated by the lords of the Underworld in an earlier era [31].

At a later time, the maize god was resurrected by his sons the Hero Twins, who were able to overcome the Underworld gods [32, 33]. Thereafter, human life became possible, once the location where the grains and maize were hidden was located and its bounty released by the rain god Chaak and the deity K’awil, who represents both the lightning bolt and the embodiment of sustenance and abundance [34, 35].8

The deities of importance to this story include the maize god Nal, Chaak, K’awil, and various Underworld lords, including the paramount death god (named Kimil in some sources) and a deity known by the designation God L. God L played various roles in Maya mythology, representing a merchant deity, an Underworld lord, and a Venus god.

The Role of Cacao in the Northern Maya Area

Previous discussions of cacao in Maya culture emphasize its use and depiction in Classic period contexts (ca. 250–900 CE) from the southern Maya lowlands. The focus of this chapter is on cacao from the northern Maya lowlands, the area known today as the Yucatán Peninsula. In this region, cacao becomes visible in the archaeological record during the Late Classic period, where it is mentioned in glyphic texts inscribed on pottery in the style known as Chocholá [37, 38]. Additionally, recent investigations suggest that it was grown in dampareas such as collapsed caves and cenotes (sinkholes) [39, 40].

Following the conquest of the Yucatán Peninsula by the Spanish in the early 16th century, we learn from European chronicles that cacao was important in various rituals, and that it was grown both locally on plantations and imported from Tabasco and Honduras [41–43]. Additionally, BishopDiego de Landa, writing in ca. 1566, noted that cacao beans formed a unit of currency for exchange and were given in tribute. The owners of cacao plantations celebrated a ritual in the month of Muwan (corresponding to late April and early May) to several deities, including Ek’Chuwah, who was the god of merchants [44]. Cacao was also mixed with sacred water and crushed flowers and used to anoint children and adolescents participating in an initiation ceremony, or what Landa termed a “baptism” ritual [45]. Landa further noted that:

They make of ground maize and cacao a kind of foaming drink which is very savory, and with which they celebrate their feasts. And they get from the cacao a grease which resembles butter, and from this and maize they make another beverage which is very savory and highly thought of. [46]

Archaeological data from sites in Yucatán, in combination with images and hieroglyphic texts painted in screenfold books (codices) and on the stones used to bridge the vaults of buildings (called capstones), are useful in reconstructing the ritual and other uses of cacao in ancient Maya society.

CACAO OFFERINGS TO THE DEITIES

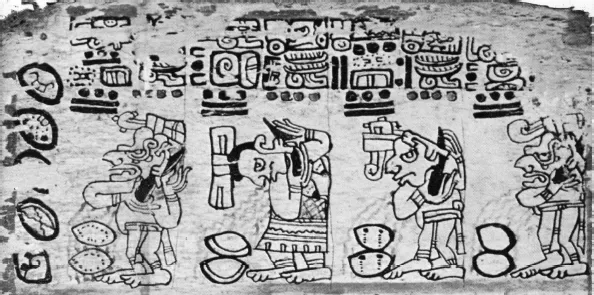

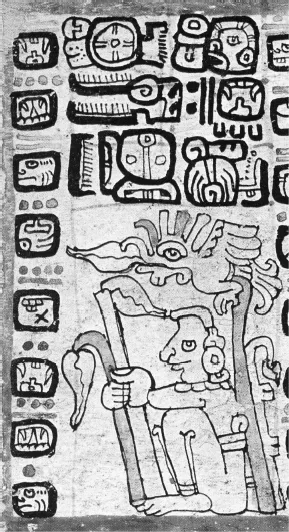

We learn, for instance, of its use as an offering to the gods in several scenes from the pre-Hispanic Maya codices, which are believed to have been painted in Yucatán during the Postclassic period.9 A scene on Dresden Codex p. 12a (Fig. 1.3), showing the god of sustenance K’awil seated with a bowl of cacao beans in his outstretched hand, recalls an offering found at the site of Ek’Balam dating to the Late Classic period, of a pottery bowl filled with carved shells replicating cacao beans. Several other almanacs from the Dresden Codex picture the plant or its beans being held by various Maya deities, including the rain god Chaak, K’awil, the death god Kimil, and the Underworld god Kisin.10 The texts associated with these almanacs describe cacao (spelled hieroglyphically as kakaw) as the god’s sustenance, or o’och [49]. We have already seen the importance of these deities in relation to cacao, and we will see further examples of the role played by K’awil below.

Another scene, this one from the Madrid Codex p. 95a (Fig. 1.4), pictures four deities piercing their ears with obsidian blades in order to draw blood. Bloodletting rituals such as these are described by Landa, who noted that piercings were made in the ear, tongue, lips, cheek, and penis [50].11 As a devout 16th century Catholic cleric, he was repulsed by these rituals, but they were an essential part of Maya religion and focused on the reciprocity between the gods (who created people out of maize and water) and people (who, in turn, were required to feed the gods with their blood) [51, 52]. It is interesting to note that Landa described women as being specifically excluded from bloodletting rituals, although one of the figures in the Madrid almanac is a female deity, as is another figure pictured letting blood from her tongue on Madrid Codex p. 40c [53]. This mirrors scenes from the Classic Maya area, where an important wife of the Yaxchilán ruler Shield Jaguar is shown drawing a thorny rope through her tongue to conjure ancestral spirits [54]

Cacao is mentioned as one of the offerings in the text on Madrid Codex p. 95a, in conjunction with incense (both pom from the copal tree and k’ik’ made from the sapof the rubber tree). Bar-and-dot numbers associated with these offerings in the text indicate the number of offerings that were given. The deities pictured in the almanac’s four frames include the creator Itzamna, a female deity associated with the earth, the wind and flower god, and a second depiction of Itzamna. Unfortunately, the glyph beginning each text caption is largely eroded, making it difficult to determine the action being referenced.12

Sophie and Michael Coe have suggested that the blood in the almanac is pictured falling from the deities’ ears onto cacao pods in the four frames illustrated [55]. It is difficult to tell what this object is, since its appearance is fairly nondescript. It is possible that, rather than depicting cacao, the elliptical objects represent some sort of paper-like material, since blood was usually collected on such strips and then burned in order to reach the gods in the Upperworld [56]. The Lacandón Maya of Chiapas still practice rituals similar to those depicted in the codices; a red dye called annatto (also known as achiote) is used in place of human blood, but it has the same general significance [57].

CACAO IN ASSOCIATION WITH OTHER PRECIOUS OBJECTS

Another interesting correspondence in both the codices and other painted scenes is the association between cacao and the birds known as quetzals (Pharomachrus mocino). In the Madrid Codex, for instance, the deity Nik, whose associations include wind, life, and flowers, leans with his back against a cacao tree, grasping a second cacao plant with his hand (Fig. 1.5). A quetzal bird appears above the scene, with a leaf in its beak. The text above the frame includes a reference to the god Nik, who is described as a day-keeper or priest; this is followed by the glyphic collocation for cacao.

This scene recalls one of the mural paintings in the Red Temple at the Late Classic site of Cacaxtla in Tlaxcala (Fig. 1.6). Although located in the Mexican highlands, the murals reflect the Maya style and were probably painted by a Maya artist [58]. The scene in question pictures the Classic Maya merchant god, God L, standing in front of a blue-painted cacao tree; a quetzal is perched on (or about to land on) the tree. Simon Martin suggests that this scene corresponds to the Underworld realm [59]. Although they come from very different environments, it is not difficult to imagine what served to link cacao and quetzals in the minds of the Maya who painted these images—both were exotic trade items and had sacred associations.

In later times, as discussed previously, the merchant deity Ek’ Chuwah—a Maya god with clear links to Yacatecuhtli, the Aztec deity of merchants and travelers—was also one of the patrons of cacao. During the month Muwan (corresponding to late April and early May), the owners of cacao plantations in Yucatán celebrated a festival in honor of this deity. Additionally, travelers and merchants prayed to Ek’ Chuwah and burned incense in his honor when they stopped to campfor the night. Landa noted that:

Wherever they came they erected three little stones, and placed on each several grains of the incense; and in front they placed three other flat stones, on which they threw incense, as they offered prayers to God whom they called Ek Chuah [Ek’ Chuwah] that he would bring them back home again in safety. [60]

Three stones were also used to build one’s hearth, in replication of the original three stones set in the sky by the gods at the time of creation. This is illustrated in a scene from the Madrid Codex p. 71a (Fig. 1.7), which shows the turtle (corresponding to the constellation Orion) as the celestial location where the stones were set [61].13

CACAO IN MARRIAGE RITUALS

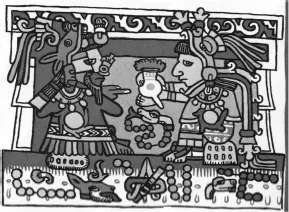

One of the most interesting of the almanacs featuring cacao in the Maya codices occurs on p. 52c of the Madrid Codex (Fig. 1.8). Its text reads: tz’á’ ab’ u kakaw cháak ix kàab’ “Chaak [the rain god] and Ixik Kaab’ [the earth goddess] were given their cacao.”14 Recently, Martha Macri pointed out that the verb ts’ ab’ a is defined as “payment of the marriage debt [from the wife to the husband or between marriage partners]” in the Cordemex dictionary [65, 66]. This calls to mind rituals pictured in the codices from the Mixtec area of highland Mexico, where a frothy cacao beverage is exchanged by those being married (see Fig. 1.2) [67]. Contemporary Mayan speakers in the Guatemalan highlands still follow this tradition. In a folktale from the Alta Verapaz region of Guatemala, the marriage vows are sealed with a vessel full of “foamy chocolate” [68].

In the Madrid Codex scene, the deity pair stands across from each other, holding what may be honeycomb in the...