eBook - ePub

Evidence-Based Nursing

An Introduction

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evidence-Based Nursing

An Introduction

About this book

What is evidence-based nursing? Simply, it is the application of valid, relevant, and research-based information in nurse decision-making. Used effectively, evidence-based nursing methods can be used to dramatically enhance patient care and improve outcomes.

Evidence-based Nursing is a practical guide to evidence-based nursing for students and practitioners. Proceeding step-by-step, it enables nurses to understand and evaluate the different types of evidence that are available, and to critically appraise the studies that lay behind them. It also considers the ways in which these findings can be implemented in clinical practice, and how research can be practically applied to clinical-decision making.

- Easy to use step-by-step approach

- Explores all aspects of the evidence-based nursing process

- Includes updates of popular articles from Evidence-based Nursing

- Examines dissemination and implementation of research findings in clinical practice

- Includes clinical scenarios

- Chapters include learning exercises to aid understanding

Evidence-based Nursing is a vital resource for students and practitioners wanting to learn more about research based nursing methods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

AN INTRODUCTION TO EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING

What is evidence-based nursing, and why is it important?

The term ‘evidence-based’ is really very new. The first documented use of the term is credited to Gordon Guyatt and the Evidence Based Medicine Working Group in 1992.[1] They described evidence-based medicine as ‘a new paradigm for medical practice’, in which evidence from clinical research should be promoted over intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiology.[1] Shortly thereafter, the term was applied to many other aspects of health care practice and further afield. We now have evidence-based nursing, evidence-based physiotherapy,* and even evidence-based policing[2] (see Box 1.1 for more examples)! Definitions vary, and sometimes the central concept becomes diluted, but at its core evidence-based ‘anything’ is concerned with using valid and relevant information in decision-making. In health care, most people agree that high-quality research is the most important source of valid information, along with information about the specific patient or population under consideration. Evidence-based ways of thinking have emerged from the discipline of clinical epidemiology, which focuses on the application of epidemiological science to clinical problems and decisions (epidemiological science is the study of health and disease in populations). These roots in epidemiology have enabled the development of a clear-sighted framework for thinking about research and its application to decisionmaking, and it is these concepts and approaches that we discuss in this book.

Box 1.1 Examples of evidence-based everything[2]

Evidence-based medicine

Evidence-based dentistry

Evidence-based physiotherapy

Evidence-based pharmacy

Evidence-based conservation

Evidence-based crime prevention

Evidence-based education

Evidence-based government

Evidence-based librarianship

Evidence-based social work

Evidence-based software engineering

Evidence-based sports

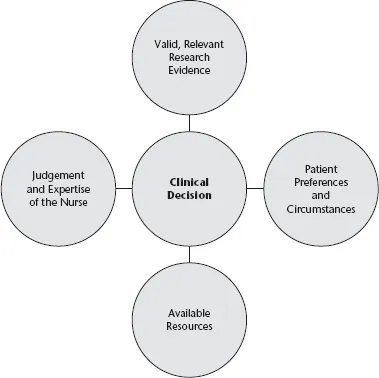

Evidence-based nursing can be defined as the application of valid, relevant, research-based information in nurse decision-making. Research-based information is not used in isolation, however, and research findings alone do not dictate our clinical behaviour. Rather, research evidence is used alongside our knowledge of our patients (their symptoms, diagnoses, and expressed preferences) and the context in which the decision is taking place (including the care setting and available resources), and in processing this information we use our expertise and judgement. The inputs to evidence-based decision-making are depicted in Figure 1.1. Research has shown, however, that many practitioners simply don’t see research evidence as being useful and accessible when making real-life clinical decisions.[3] The grand challenge is therefore showing how this can be achieved, and the quality of care enhanced.

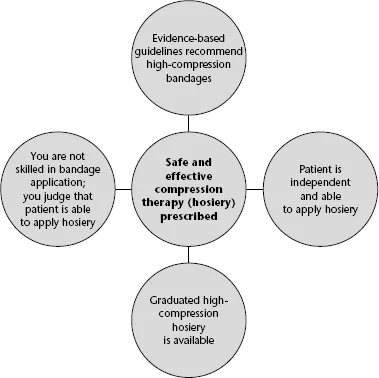

Imagine that, as a community-based nurse, you are responsible for providing care to an otherwise fit 74-year-old man with a chronic venous leg ulcer. Your locally relevant, evidence-based, leg ulcer guideline tells you that high-compression bandaging, such as the four-layer bandage, should be the first line of treatment, is eminently deliverable in a community setting, and is cost-effective.[4] You have been trained, and are competent, in the application of this bandage and, therefore, proceed to prescribe it for this patient. Contrast this decision with an alternative scenario, one in which all variables are the same, except that you are inexperienced in bandage application. You know that poor bandage application technique can have disastrous consequences for the patient – including amputation. Under these circumstances, you decide to prescribe graduated compression hosiery (stockings) rather than bandages. You know that graduated compression hosiery applies a similar level of compression to the four-layer bandage, and, after determining that the patient is able to apply the stockings himself, you concede that these will also be the safer option given your lack of skill in bandaging. If your patient had arthritic hands and was unable to apply stockings, or did not have the facilities to wash the stockings, your decision would probably have been different (see Figure 1.2). At any given time, the research evidence informing a decision is a constant; however, you must use your professional judgement to determine how you will apply it to the patient in front of you. Obviously, it is also important to remember that, as new research is published, the evidence base will change, and you will need to become aware of important changes in evidence relevant to your practice (see Chapter 5 for information on alerting services).

Figure 1.1 The components of an evidence-based nursing decision.

Figure 1.2 Resolution of a decision problem: how research evidence, judgement, patient preferences and circumstances, and knowledge about local resources interplay.

Getting started with evidence-based nursing

There are many ways to begin introducing research evidence into practice. At the simplest level, you might identify an area of practice for which you are responsible, find out if any evidence-based clinical practice guidelines exist, critically appraise them to determine if they are valid, and consider how they might be applied locally. Chapter 26 outlines this very process. In areas where guidelines don’t exist, you might, in collaboration with colleagues, identify recurring uncertainties in your clinical area. Next, you would translate your single uncertainty (e.g. Is it really necessary for people to lie flat for 8 hours after lumbar puncture?) into a focused, answerable question. Chapter 3 outlines how to develop focused, answerable questions. For the lumbar puncture example, the question might be as follows: In patients having cervical or lumbar puncture, is longer bed rest more effective than immediate mobilization or short bed rest in preventing headache? This question is clearly about whether a particular intervention (lying flat for a long time) is better or worse than an alternative (not lying flat or lying flat for a brief time). Chapters 7 and 8 explain how certain types of clinical question demand research evidence from particular research designs because the answers are more likely to be valid, or true. In the above example, where the question concerns an intervention or therapy, the answer is best provided by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (or, even better, by a systematic review of all relevant RCTs). You would then move into the searching phase to identify relevant RCTs or reviews; Chapters 4, 5 and 6 will guide you through the searching process. The next step is to grapple with assessing the quality of the research you find. We cannot accept the results of research at face value because, irrespective of where research has been published, and by whom, most research is not fit for immediate application. This is best illustrated by the fact that only about 5.4% of the approximately 50 000 articles published in 120 journals, and scrutinized for three evidence-based journals (Evidence-Based Nursing, Evidence-Based Medicine, and ACP Journal Club), reached the required methodological standard (personal communication, A McKibbon, 20 December 2006).

Fortunately several resources of pre-appraised research now exist, and these are discussed in Chapter 4. If your search does not identify any pre-appraised evidence, you will need to appraise the research you find so that you can judge whether the results are valid and ready for use in practice. Chapters 15–26 lead you through the process of critically appraising reports of study designs you will commonly encounter. Finally, Chapters 27–32 consider different aspects of research utilization: theoretical models (Chapter 27), empirical evidence of interventions aimed at changing professional behaviour (Chapter 28), the influence of the organization on research utilization (Chapter 29), use of research in clinical decision-making (Chapter 30), the emergence of computerized decision support systems in nursing (Chapter 31), and one hospital’s experiences of promoting evidence-based nursing (Chapter 32).

Context

The emergence of evidence-based practice could not have happened at a more important time for nursing. The role of the nurse is not a fixed phenomenon; it varies by geography and culture and is heavily influenced by parameters such as the national economy and the supply of doctors. As we write this book at the beginning of the 21st century, never has the demand for health care been so high, and most countries are struggling to meet this demand. The flexibility inherent in the nursing role is widely used to respond to this demand for health care. For example, in 2000, the United Kingdom (UK) Department of Health’s Chief Nursing Officer announced 10 new roles for nurses, and nurses are now adopting these new roles widely (Box 1.2).[5] These new roles were previously held only (formally, at least) by doctors (e.g. prescribing drugs,† ordering diagnostic tests, etc.). It is difficult to imagine how nurses will be able to take on these challenging new roles and responsibilities without developing knowledge of clinical epidemiology and adopting an approach to decision-making that is informed by evidence.

Box 1.2 The Chief Nursing Officer’s 10 new roles for nurses[5]

1. Ordering diagnostic investigations

2. Making referrals

3. Admitting and discharging patients within protocols

4. Managing caseloads of people with chronic conditions such as diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis

5. Running clinics (e.g. dermatology)

6. Prescribing medicines and treatments

7. Carrying out a wide range of resuscitation procedures

8. Minor surgery

9. Triage patients

10. Planning service organization and delivery

At this point, it is probably worth pausing to reflect on how quickly nursing research has developed. The first nursing research journal (Nursing Research) was only launched in 1952. Early nursing research mainly used methodologies taken from the social sciences and largely focused on nurse education and nurses themselves. The second issue of Nursing Research contained nine research articles, four of which were about nursing students and nurse education. Since these early days, nursing research has developed apace, and there are now more than 1200 journals indexed in CINAHL, with 5400 research articles (identified by the search term ‘nurs$’) entering the CINAHL index in the year 2005 (searched by N. Cullum, 8 January 2007). In 1998, the Evidence-Based Nursing journal was launched, only 3 years after the launch of Evidence-Based Medicine (both published by the BMJ Publishing Group).

Early evidence of the impact of evidence-based practice on policy, education and research

Evidence-based practice in general, and evidence-based nursing in particular, can be viewed as complex innovations, and it would be naïve to expect rapid and comprehensive uptake. Nevertheless, there is ample evidence of the impact of ‘evidence-based’ thinking on policy and education, paralleled by a rapidly growing research evidence base in clinical nursing topics. The Nursing and Midwifery Council, which governs nursing professional practice and nurse education in the UK, outlines in its Code of Conduct an expectation that nurses will ‘deliver care based on current evidence, best practice and, wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTRIBUTOR LIST

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- DEDICATION

- COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Chapter 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING

- Chapter 2: IMPLEMENTING EVIDENCE-BASED NURSING: SOME MISCONCEPTIONS

- Chapter 3: ASKING ANSWERABLE QUESTIONS

- Chapter 4: OF STUDIES, SUMMARIES, SYNOPSES, AND SYSTEMS: THE ‘4S’ EVOLUTION OF SERVICES FOR FINDING CURRENT BEST EVIDENCE

- Chapter 5: SEARCHING FOR THE BEST EVIDENCE. PART 1: WHERE TO LOOK

- Chapter 6: SEARCHING FOR THE BEST EVIDENCE. PART 2: SEARCHING CINAHL AND MEDLINE

- Chapter 7: IDENTIFYING THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN TO FIT THE QUESTION. PART 1: QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

- Chapter 8: IDENTIFYING THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN TO FIT THE QUESTION. PART 2: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- Chapter 9: IF YOU COULD JUST PROVIDE ME WITH A SAMPLE: EXAMINING SAMPLING IN QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE RESEARCH PAPERS

- Chapter 10: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF QUANTITATIVE MEASUREMENT

- Chapter 11: SUMMARIZING AND PRESENTING THE EFFECTS OF TREATMENTS

- Chapter 12: ESTIMATING TREATMENT EFFECTS: REAL OR THE RESULT OF CHANCE?

- Chapter 13: DATA ANALYSIS IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- Chapter 14: USERS’ GUIDES TO THE NURSING LITERATURE: AN INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 15: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF TREATMENT OR PREVENTION INTERVENTIONS

- Chapter 16: ASSESSING ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT AND BLINDING IN RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS: WHY BOTHER?

- Chapter 17: NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT: A CLINICALLY USEFUL MEASURE OF THE EFFECTS OF NURSING INTERVENTIONS

- Chapter 18: THE TERM ‘DOUBLE-BLIND’ LEAVES READERS IN THE DARK

- Chapter 19: EVALUATION OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS OF TREATMENT OR PREVENTION INTERVENTIONS

- Chapter 20: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF SCREENING TOOLS AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

- Chapter 21: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF HEALTH ECONOMICS

- Chapter 22: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF PROGNOSIS

- Chapter 23: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF CAUSATION (AETIOLOGY)

- Chapter 24: EVALUATION OF STUDIES OF TREATMENT HARM

- Chapter 25: EVALUATION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH STUDIES

- Chapter 26: APPRAISING AND ADAPTING CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

- Chapter 27: MODELS OF IMPLEMENTATION IN NURSING

- Chapter 28: CLOSING THE GAP BETWEEN NURSING RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

- Chapter 29: PROMOTING RESEARCH UTILIZATION IN NURSING: THE ROLE OF THE INDIVIDUAL, THE ORGANIZATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 30: NURSES, INFORMATION USE, AND CLINICAL DECISION-MAKING: THE REAL-WORLD POTENTIAL FOR EVIDENCE-BASED DECISIONS IN NURSING

- Chapter 31: COMPUTERIZED DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS IN NURSING

- Chapter 32: BUILDING A FOUNDATION FOR EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: EXPERIENCES IN A TERTIARY HOSPITAL

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evidence-Based Nursing by Nicky Cullum, Donna Ciliska, Brian Haynes, Susan Marks, Nicky Cullum,Donna Ciliska,Brian Haynes,Susan Marks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nursing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.