![]()

Part I

The Making of a World Religion: Christian Mission through the Ages

![]()

1

From Christ to Christendom

In 1970 the British rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar hit the shelves of record stores. The deceased Judas, who betrayed Jesus to the authorities who crucified him, appears in the afterlife and sings the title song, “Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ, who are you, what have you sacrificed? Jesus Christ, Superstar, do you think you’re what they say you are?” Referring to Jesus’ humble origins in Palestine, an obscure province conquered by the Roman Pompey in 63 BC, Judas asks him, “Why’d you choose such a backward time and such a strange land? If you’d come today you would have reached a whole nation. Israel in 4 BC had no mass communication.”

The conservative Christian establishment found the portrayal of an earthy “rock and roll” Jesus with his long hair and hippie commune of male and female disciples to be disrespectful, if not sacrilegious. But for many American baby boomers in the 1970s, Jesus Christ Superstar blew like a fresh breeze across their predictable and boring suburban churches. Suddenly Jesus seemed like one of them. He defied authority, was filled with self-doubt, and “hung out” with a pack of friends. Even before the rock opera opened on Broadway and in London, American high school students bought the record and staged their own productions.

At the same time, behind the Iron Curtain in Estonia, Soviet communism persecuted religions and denied education to active Christians. In the early 1970s, teenagers huddled in secret, listening to illegal recordings of Jesus Christ Superstar smuggled from the United States. The combination of the outlawed religion with forbidden western rock music was a potent mixture. Years later, a leading Estonian Christian reminisced that his first real understanding of the faith had come from the humanity of the rock-and-roll Jesus he secretly encountered in Jesus Christ Superstar. In the decades since it opened, the rock opera has been performed in Central America, eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and around the world.

While on one level Jesus Christ Superstar is a money-making musical, on another level its transcendence of Cold War geopolitical divisions – and the appeal of its rock-and-roll Jesus to youth everywhere – exemplifies the remarkable cultural fluidity of the Christian religion across the centuries. Whether told through music, art, sermons, or books of theology, the story of Jesus is repeatedly translated anew. Because of its embodiment in human cultures – an idea that theologians refer to as “incarnation” – the Christian message has outlasted clans and tribes, nations and empires, monarchies, democracies, and military dictatorships. When a handful of Jesus’ Jewish followers reached out to non-Jews in the Roman empire, they unknowingly set their faith on the path toward becoming a world religion. It appears that Israel in 4 BC was not such a “backward” place after all.

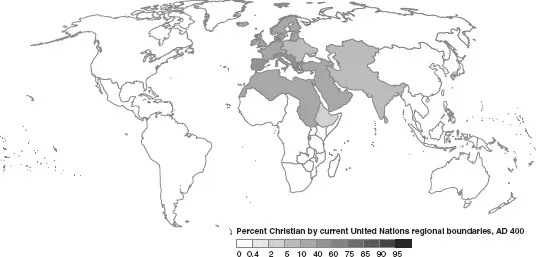

By the third century AD, Christians could be found from Britannia in the north to North Africa in the south, from Spain in the west to the borders of Persia in the east. The eastward spread of Christianity was so extensive that the fourth-century Persian empire contained as high a percentage of Christians as the Roman, with a geographic spread from modern-day Iran to India. By the seventh century, Christians were living as far east as China and as far south as Nubia in Africa.

The rise of Islam in Arabia during the seventh century halted Christianity’s eastward and southward expansions. Although Arab armies conquered the country of Jesus’ birth, by the end of the first millennium after his death the Christian religion had pushed northward across Russia, Scandinavia, and Iceland. The first Christian arrived in North America in AD 986 when a short-lived colony settled in Greenland. By the late sixteenth century, substantial groups of indigenous Christians were thriving in Angola, Japan, the Philippines, Brazil, and Central America. By the early seventeenth century, South Africa, Vietnam, and First Nations Canada all had significant Christian populations. During the nineteenth century Christianity spread across North America, North Asia, the South Pacific, and into different regions of Africa. The most rapid expansion of Christianity took place in the twentieth century, as pockets of Christians throughout Africa and Asia grew into widespread movements.

But the story of Christianity around the world is not that of a simple, linear progression. To become a world religion, Christianity first had to succeed on the local level. Specific groups of people had to understand and shape its meaning for themselves. What in totality is called a “world” religion is, on closer observation, a mosaic of local beliefs and practices in creative tension with a universal framework shaped by belief in the God of the Bible, as handed down through Jesus and his followers. As a world religion, Christianity thrives at the intersection between the global or universal, and the local or personal.

A complicating factor in charting the spread of Christianity is that its expansion has not been a matter of continuous progress. Rather, growth takes place at the edges or borderlands of Christian areas, even as Christian heartlands experience decline. Christianity has wilted under assault from hostile governments, ranging from the Zoroastrian Persians in the fourth century to the communist takeover of Russia that killed millions of believers in the twentieth century. When circumstances change, loss of meaning can hollow out the faith from within. In the wake of two devastating world wars, secularism swept over Europe in the late twentieth century, and the percentage of practicing Christians dropped. The pattern that historian Andrew Walls calls “serial progression,” including expansion and contraction over time, means that the history of Christianity cannot be treated as a monolithic enterprise, with its universal spread a foregone conclusion. By the mid twenty-first century, the most populous Christian areas of the world are projected to be in the southern hemisphere, in Africa and South America.

The following chronology defines the history of Christianity as a movement rather than a set of doctrines or institutions, notwithstanding that doctrines and institutions are important markers of group identity. As a historical process, Christian mission involves the crossing of cultural and linguistic boundaries by those who consider themselves followers of Jesus Christ, with the intention of sharing their faith. The ongoing boundary crossings raise the question of how the meaning of “Christian” continues to include culturally disparate groups of people: how does Christian identity change as it crosses cultures? The reverse question is also important, namely, how does Christianity shape the culture or worldviews of those who encounter it?

From Jerusalem into “All the World”

The creation and expansion of Christianity began with Jesus, a devout Jewish man who lived 2,000 years ago, never left Palestine, had a public ministry of only three years, and was executed by Roman authorities at age 33 by being nailed to a cross of wood in the manner of common criminals. Government officials hunted down and executed his most important followers. Yet within three centuries of his death, an estimated 10 percent of people in the Roman empire ordered their lives around communal memories of his life and teachings, faith in the defeat of death itself, and the affirmation that he was the “Christ” or “Lord,” the unique embodiment of the one true God.

The writings generated by Jesus’ disciples are the starting point for understanding the cross-cultural process of Christian adaptation. The New Testament was itself a collection of missionary writings written to help a scattered community remember its origins, and to provide a framework that described and justified the expansion of the faith beyond the first Hebrew believers. Documents were written in the commercial lingua franca of the Roman empire, common Greek, and then compiled into a portable book form, or codex. Greek was the language of philosophy, and so was well suited to the expression of theological ideas. By the second century after Jesus’ death, the Greek texts had been translated into Latin and Syriac, other major languages of the Mediterranean and western Asia.

The infrastructures of the Roman empire provided unprecedented opportunities for the spread of information from one region to another. With the Pax Romana, or peace enforced by Rome, followers of “the Way” – as early followers of Jesus called themselves – moved along the good Roman roads into the major cities of the empire, carrying letters of introduction from believers in other cities that convinced strangers to open their doors and host the traveling teachers.

Diaspora Jews scattered throughout the empire, in a wide variety of occupations, were interested in stories of one who had wandered as a teacher and healer in the mode of the biblical prophets, and who claimed to represent a fulfillment of Jewish destiny. And non-Jews, or “Gentiles” in Jewish parlance, sometimes admired the Jewish people for their ethical uprightness and belief in one God, and so were drawn to new interpretations of the Hebrew Scriptures that welcomed non-Jewish members.

The idea of “mission” is carried through the New Testament by 206 references to the term “sending.” The main Greek verb for “to send” is apostellein. Thus apostles were literally those sent to spread the “Good News” of Jesus’ life and message. Notable passages in the New Testament contain explicit commands to go into the world to announce the coming of God’s reign, such as when Jesus sent seventy followers to preach to the Jews (Luke 10:1–12). After his resurrection from death and appearance to Mary Magdalene and other women who had gone to his tomb, Jesus told the women to “go tell” his male followers that they had seen him alive.

The most famous biblical passage used by Christians to encourage each other to spread the word about Jesus’ life, work, and defeat of death occurred when after his resurrection Jesus ordered the gathered disciples to “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:19–20). The book of John phrased Jesus’ post-resurrection counsel to the disciples with the words, “As the Father has sent me, so I send you” (John 20:21).

Despite intermittent opposition from the Roman authorities, from Jewish religious leaders, and from adherents of Greek and Roman gods, early followers of “the Way” organized themselves into gathered communities called ekklesia, or churches. Dozens of different biblical expressions were used to describe the public witness or missionary existence of the ekklesia, such as “light to the world,” “salt of the earth,” and “city on a hill.” Churches, therefore, were both the products of mission and the organizational network behind further spread of the message.

A century ago, theologian Martin Kähler remarked that mission is “the mother of theology.” Although the New Testament is not a systematic handbook of theology, its missionary character reveals that the early followers of Jesus believed they had a divine mandate to bear witness to what they had seen of his ministry, of his message, and especially of his stunning reappearances after the crucifixion. Early Christians believed that Jesus was fulfilling the Jewish prophecies that someday a Savior or Messiah would come to save Israel and inaugurate God’s reign on earth. The significance for the history of Christian mission does not lie in the numerous modern debates over the historical accuracy of the events around Jesus’ death and miraculous resurrection, but rather in what the New Testament shows about the missionary consciousness of the early Christians. The transformation of a cowed and defeated handful of Jewish followers into a death-defying, multi-cultural missionary community was an amazing beginning to what is now the largest religion in the world.

The Apostle Paul as missionary

While the core followers of Jesus when he was alive were known as “disciples,” Paul is remembered as the “apostle” to the Gentiles, or in modern terms a “missionary” – “one who is sent.” Scores of books have been written about Paul as the archetype of the cross-cultural missionary, on Paul’s mission strategy, or “Pauline” methods in missions. Yet Paul was only one of dozens of believers who traveled around the Roman empire, spreading the “Good News” about Jesus as Messiah, the chosen one of God. Paul has been remembered as the model missionary by Christians down through the centuries not just because he traveled an estimated 10,000 miles for his mission, but because the letters to the churches he founded are the oldest documents gathered into the New Testament and are foundational to Christian theology. The narrative of Paul’s ministry is contained in the Acts of the Apostles, the fifth book in the New Testament.

Paul’s personal story makes gripping reading: a follower of a Jewish religious sect called the Pharisees, a law-abiding and duly circumcised member of the tribe of Benjamin, and a Greek-speaking Roman citizen, Paul began his relationship with Christians by persecuting them. The followers of Jesus were standing up in synagogues and proclaiming that Jesus represented the fulfillment of Jewish Scriptures about the coming Messiah. When one of the early church officers named Stephen was stoned to death for blasphemy, Paul held the coats of the mob.

Yet one day, on his way to arrest some Christians in Damascus, Paul was blinded by a flash of light and heard the voice of Jesus asking him why he was persecuting him. After three days of blindness, Paul was visited by a church leader who restored his eyesight and told him how Jesus had been resurrected from death (Acts 9:1–19). This transformative experience was interpreted by Paul as God calling him to preach to Greek-speaking Jews and Gentiles on behalf of “the Way” of Jesus Christ.

Propelled by his vision, Paul traveled to provincial centers where he sought out the Jewish quarters and began proclaiming the message of Jesus as Messiah. Because the diaspora Jews scattered throughout the empire spoke Greek, and worked and traded in the wider Greek-speaking world, many had forgotten their native Hebrew. In the third century BC Jewish Scriptures had been translated into a Greek version called the Septuagint. As Paul interpreted the salvific role of Jesus according to the Hebrew Scriptures, he could be understood both by ethnic Jews and by non-Jews. The common Greek language – as well as Paul’s theological interpretations – were bridges across which the meaning of Jesus’ defeat of death traveled from an oral, Aramaic-speaking local Hebrew culture into the cosmopolitan Greek world. The Greek word for Messiah, or Lord, is “Christ.”

In Antioch, where Paul spent a year, a decisive breakthrough among Greek-speaking Gentiles occurred, and the followers of the Way of Jesus began to be called “Christians.” Paul’s basic message was one of inclusion: through Jesus Christ, Gentiles were grafted on to God’s promises for Israel: “For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; the same Lord is Lord of all and is generous to all who call on him. For, ‘Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved’ ” (Romans 10:12–13). The biculturality of the diaspora Jewish population, as exemplified by Paul himself – a Greek-speaking Jew – was essential for the expanded meaning of salvation that included both Jews and Greeks. After Paul had gathered a community of believers in a particular city he moved on, but sent other workers to help the fledgling churches he had visited. A network of Christians – linked together by correspondence and itinerant teachers like Paul – began emerging in the cities across the Roman empire.

As more non-Jews were attracted to the Christian community, tensions grew between the Jewish believers, who continued to worship in synagogues and to follow Jewish law, and the new believers from other ethnic backgrounds for whom the Jewish law was unimportant. Many of Paul’s letters dealt with the struggles of the infant churches to negotiate their internal cultural and economic differences. After fourteen years of successful ministry among the growing Gentile churches, Paul was summoned to Jerusalem to meet with the Hebrew Christians, directed by Jesus’ brother James. The Christians in Jerusalem were skeptical that the non-Jewish Christians could be fully accepted by God without obeying Jewish law. In a crucial discussion, described in Acts 15, Jesus’ chief disciple Peter, Paul, and his friend Barnabas convinced James and the Hebrew church elders that God was clearly speaking to the Gentiles. Evidence of God’s love for non Jews was to be found in the miraculous healings and changed lives, the “signs and wonders,” being performed among them. The Jerusalem Christians sent off Paul and Barnabas with some minimal instructions and a generous blessing for the non-Jewish Christians. This approval by the “Jerusalem Council” of Jewish leaders who had been close to Jesus himself ratified Christianity’s already vigorous expansion into Syria, Cilicia, Antioch, and points eastward.

That ...