- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Winner of the 2010 James M. Blaut Award in recognition of innovative scholarship in cultural and political ecology (Honors of the CAPE specialty group (Cultural and Political Ecology))

Decolonizing Development investigates the ways colonialism shaped the modern world by analyzing the relationship between colonialism and development as forms of power.

- Based on novel interpretations of postcolonial and Marxist theory and applied to original research data

- Amply supplemented with maps and illustrations

- An intriguing and invaluable resource for scholars of postcolonialism, development, geography, and the Maya

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Colonizing the Maya

1

Unsettling the Colonial Geographies of Southern Belize

The history of the subaltern classes is necessarily fragmented and episodic; in the activity of these classes there is a tendency toward unification, albeit in provisional stages, but this is the least conspicuous aspect, and it manifests itself only when victory is secured. Subaltern classes are subject to the initiatives of the dominant class, even when they rebel; they are in a state of anxious defense. Every trace of autonomous initiative is therefore of inestimable value.

Antonio Gramsci, 19301

In 1918, John Taylor, former warden of the colonial prison and then District Commissioner of the relatively new Toledo District of southern British Honduras (as Belize was then known), typed these words regarding the “Indian question” to his superiors:

Much could be written on the subject of [the] Indian population, – they are interesting, – I for one would like to see an improvement in this (to my mind) – fast decaying Race, – they are, especially youngsters Bright and Quick to learn, – and although these kiddies when in school appear to me studious, and seem to enjoy it, yet they much prefer – the Boys – to shoulder a Machete and strut off with Father to the Milpa. Any improvement in their mode of living, or agricultural methods, can only be brought about by others foreign to them, either by example or inducement, – Force beyond a certain point will not do.2

By the time Taylor typed these lines in his Punta Gorda office, British policies and positions towards the Mayas in Belize were well established.

The Mayas were to live within Indian reservations, supervised by alcaldes who were incorporated into the colonial state. Alcaldes were responsible for collecting land taxes and enforcing colonial law. Living in settled villages and attending school were mandatory (though education was left to the Catholic church). To sum up British policy in a word – one that appears frequently in the colonial archive – the Maya were to be settled.

Like many of the colonial texts of the era, Taylor’s comments are replete with the essentialist tropes about those he was sent to govern. Unelected and racist he may have been, John Taylor was the sole legal authority and magistrate of the Toledo District for more than ten years. Even the minor texts and statements of such colonial officials had concrete effects. For instance, Taylor’s claim that the Mayas are by nature “childlike” and “fast decaying” calls for the intervention of a paternal state to act as trustee for the Maya, frames the Maya as racialized subjects, and solicits the state as a development institution (to end the decay). We must pay attention to such texts, since it is by analyzing colonial discourse that we may come to understand colonial hegemony, understood in Gramsci’s sense as the forms of moral and intellectual leadership that ramify through cultural practices and sustain unequal social relations.3 Social groups compete for hegemony in order to consolidate projects that facilitate capital accumulation to their advantage. Taylor’s argument that “force beyond a certain point will not do” stands as evidence of Gramsci’s insight. Taylor was keenly attuned to the problem of calibrating the use of force: hence his qualification that “Force beyond a certain point will not do.” Force is needed, but only to a point. How is the point defined? Not ethically, but in terms of efficiency. Beyond a certain point, the costs and difficulties of coercion – including the likelihood of provoking resistance – outweigh the benefits of the desired change. Hegemony names this “certain point.” It is the constellation of forces that “will do” – that produces consent. The British colonial state was authoritarian, but it could not maintain overwhelming force or rule through explicit coercion. The colonial state there – like colonial power generally – needs consenting subjects and territorialized spaces. This chapter aims to discern these forms of colonial hegemony, subjects, and territorial spaces.

The Colonization of Southern Belize

Two narratives orient the historiography of Belize: one tells of the heroic victories of the British settlers in their conflicts with Spain and the Mayas; the other relates the unfolding discovery of the nation’s geography through scientific exploration and description. Both narratives are geographically deterministic insofar as they suggest that Belize’s history is a function of its geographical location, climate, and resources.4 Moreover, they frame Belize’s history teleologically. Thus colonialism and capitalism are quite literally naturalized. Consider Lucas’s summary of Belize’s history:

From an historical point of view, British Honduras is a very interesting instance of the evolution of a colony. It began with private adventurers, who held their own in spite of a strong foreign power [Spain] and whose success practically obliged their own government to afford them some measure of recognition and protection. It originated with trade, trade begat settlement, and settlement brought about in fullness of time a colony.5

Framed in this way, the historical development of Belize is reduced to the mechanistic unfolding of colonial capitalism, a natural development. Insofar as agency is attributed to historical actors, it is located with the British settlers – and, to a lesser degree, their Spanish competitors. Contingencies in the flow of this history are attributed to heroic Europeans. This sort of teleological historiography justifies colonialism and marginalizes non-European subaltern voices.

British buccaneers from Jamaica settled at points along the Central American coast in the 1650s, including the delta of the Belize River, where they began cutting logwood for export to England. Two centuries later, this outpost of colonial capitalism become the capital of the British colony of British Honduras.6 The Spanish claim, legally recognized by England until 1798, delayed the development of state institutions.7 The territorial status of the area now known as southern Belize was especially unclear, since treaties between England and Spain only covered the land as far south as the Sibun River near the center of the country. Although contact between Mayas and Europeans in southern Belize may have occurred as early as the 1520s, when Cortes marched southward through the area now known as the Guatemalan Verapaz, southern Belize had not been settled by the Spanish; uncolonized, it remained a contested space, claimed by two European states yet inhabited by Manche Chol and Mopan Mayas.8

British efforts to colonize southern Belize did not commence until the colonial state was at war with Mayas in other regions of the colony. Although Maya people lived in southern Belize before the 1880s, the state had no contact with them.9 The area south of the Sibun River was essentially terra incognita to the colonial state:

The Southern portions of our territory have never been explored, and according to the Crown Surveyor they contain inhabitants who, he believes, have never yet been seen by European or creole. The rivers south of the Sibun have their source in the mountains whose line of water-shed forms the division between ourselves and Vera Paz. Adown these streams... Mr. Faber has seen floating, rough wooden bowls and other implements which testify to the existence of some inhabitants utterly unknown to us.10

The search for mahogany by European loggers drew capitalists, and the liminal colonial state behind them, towards the source of these wooden bowls. Between the 1840s and 1880s, logging crews came into occasional contact with Mayas in southern Belize, but contact between the state and the Mayas was infrequent and did not decisively shape state policy toward the Maya (there were as yet no state institutions in the south).11

The event that eventually caused the British to recognize the existence of Mayas in southern Belize was the flight of landless peasants from the Alta Verapaz into the lands around the present-day communities of Pueblo Viejo and Aguacate in the 1870s and 1880s. During this period, Guatemalan land and labor laws were changed to facilitate the expansion of capitalist agriculture. The effect of these policies was felt immediately in the Alta Verapaz (a region inhabited mainly by Q’eqchi’- and Mopan-speaking Mayas) through the explosive growth of coffee plantations. Between 1858 and 1862 alone, 75 coffee fincas were created on lands that had been held in common by Q’eqchi’ communities around Coban and Carcha. By the 1880s, thousands of Mayas had fled the Verapazes to the north, into the Peten, and to the lands along the rivers in the east. Exile denied labor to the coffee estates.12 The existing Maya communities in southern Belize – a heterogeneous group of Q’eqchi’, Mopan, and Manche Chol-speaking Mayas – grew with the influx of migrants. By the 1880s, ~1,500 Maya people were living in what is today the Toledo District – a political space that did not yet exist.13

The accumulation strategy of colonial Belize had two major elements: the export of forestry products to the US and England and the import of food and manufactured goods from England for consumption in Belize. These paired movements produced a regular flow of capital to British capitalists. Capital generated from exporting primary commodities to the US went to British manufacturing capitalists, since most of the capital generated through exports was used to import commercial goods from England. The main benefactors within the colony were the large shipping houses in Belize City that imported and sold food and manufactured goods (particularly cloth and clothing). What made this accumulation strategy especially profitable for British capital was the fact that the two most important factors of production, land and labor, were derived through primitive accumulation.14 From the perspective of British capital, the effectiveness of this strategy can be measured by the fact that the forests of Belize were almost entirely cut over twice before any substantive buildings, roads, or state institutions – apart from taxation and policing functions – were built in the colony. Throughout the nineteenth century, unprocessed mahogany logs accounted for more than half of the total value of exports from the colony. These exports peaked in the mid-1840s, a period when the European railway boom led to consistent demand for mahogany. This mahogany boom was followed by a bust triggered by overproduction: within the colony, mahogany had been overcut; and internationally, prices declined as exports to Europe and the US increased from other regions.

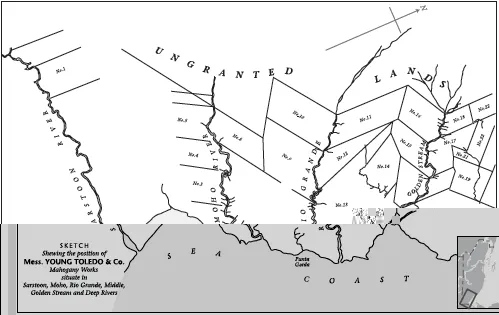

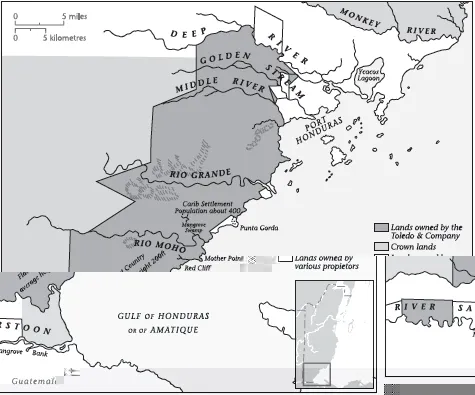

The boom and bust cycles of overcutting and land speculation occurred in the south later than the north and west. Maps from the surveyor’s department indicate a mahogany boom throughout southern Belize in the 1860s.15 Figure 1.1 shows the location of 22 concessions to log mahogany on the five southernmost rivers in Belize. At this time the land along the Golden Stream, Rio Grande, and Moho rivers was divided into logging concessions.16 These maps suggest that the extent of the logging did not go far inland, at least before 1861. (Figure 1.2 shows an overlay of the 1861 map, transformed with a GIS using the rivers as control points, onto a contemporary map of southern Belize.) The forestry concessions led to the first concerted attempt to parcelize private estates and created southern Belize’s first real estate market. By 1868, almost all of the land in a 10-mile strip near the coast, between the Temax and Deep rivers, was privately held (see figure 1.3). Many of the boundary lines of these new estate properties correspond to the boundaries of the earlier logging concessions.17

There is scant evidence that any of the capital generated by slavery and logging in the nineteenth century was reinvested in productive activities within the colony.18 Surpluses were typically invested in land speculation, which contributed to Belize’s longstanding land monopoly. In 1787 twelve settlers “owned almost all of the land” in British Honduras.19 Initially these monopolies did not cover the land in the Toledo District (which did not yet exist as such) since the lands south of the Sibun River lay beyond the treaties with Spain. Most of the land that remained was not converted into private estates until the mid-nineteenth century. Multinational firms that held sufficient capital to take advantage of the decline of mahogany in the 1850s benefited by accumulating land titles from smaller settler-owned firms. By 1881 one company, the Belize Estate and Produce Company (BEC), owned over a million acres of land – roughly half of all the private land in the colony.20 Unlike the relatively independent, small settler companies, the BEC used their power to lobby the British government to convert their logging concessions into titled property, thereby gaining power relative to the settlers and the colonial state.

Figure 1.1 Sketch map showing logging concessions, 1861

Cartographer: Eric Leinberger, 2005

Figure 1.2 Sketch map showing logging concessions, 1861 (transformed)

Cartographer: Eric Leinberger, 2005

Figure 1.3 Map of Crown and private lands, 1868 (transformed)

Cartographer: Eric Leinberger, 2005

One of the first companies to gain ground in southern Belize was the Young, Toledo, and Co., founded around 1839. The company accumulated extensive properties after the 1854 passage of the first Land Titles Acts, which converted mahogany concessions into titled property rights. By 1871 the company had acquired more than a million acres of land, including most of the private land available in southern Belize. The boom was brief. The company overextended its reach, went bankrupt in 1881, and lost its properties to the Crown.21 The colonial state thus became the main landowner in southern Belize, unlike in the north and west. The colonial state in turn sold off many of its holdings as private lands. The major benefactor of these sales was a German colonist named Bernard Cramer, who became wealthy in the 1860s and 1870s through land speculation in northern and central Belize. In the early 1880s he appears to have purchased most of the logging concessions for southern Belize, including several from Young, Toledo, and Co.22 Around 1891, Bernard Cramer’s son Herman established an estate on the Sarstoon River in the southwestern corner of the colony, which soon became the largest agricultural estate in southern Belize, producing all the coffee for the colony, as well as rubber, cocoa, and bananas. (Cramer’s estate employed a number of Q’eqchi’ Mayas who lived in and around a village known as San Pedro Sarstoon.)

For roughly a half-century, between the 1880s and the 1930s, a wide range of goods was exported from the Toledo District: mahogany, logwood, and chicle from the forests; sugar and rum from the sugar estates along the coast; bananas in the Rio Grande and Monkey River watersheds; and cocoa, rubber, coconuts, copra, plantains, and coffee from the estates and Maya communities in the interior. The forests and laborers of southern Belize also produced chicle, cacao, and cohune nut oil for export to the United States until the Depression, when export prices crashed.23 Yet the extensive production of southern Belize during the colonial period generated almost no local capital accumulation. The colonial state did little to counteract this unevenness. Almost no tax revenue was collected from the land and timber monopolies, and there is no evidence in the colonial record or on the landscape of any investment in rural Toledo.

Even into the twentieth century, state institutions remained weak in the Toledo District, partly as a result of the area’s reputation as the most unhealthy and remote in the colony. Although state institutions in southern Belize were small, the local state consistently ran deficits, especially during periods of economic growth. The mean annual revenue for the Toledo District between 1914 and 1920 was a paltry $6,889, and expenses were $18,373 – producing an average annual deficit of $11,484. Although the forestry sector dominated the colonial economy, the colonial state generated little revenue from forestry exports and did almost nothing to regulate forestry practices. Two major colonial reports signaled the danger of the overcutting of mahogany and dependence on forestry exports. The crisis arrived with the Depression. Between 1927 and 1932, the value of forestry exports fell by over 90 percent, and to compound the crisis, on September 10, 1931 a major hurricane devastated Belize City and much of the mahogany-rich forests of northern Belize.24 When export earnings collapsed, officials turned to London for Imperial grants. But at the request of the BEC and large estate-owners that owned most of the colony’s wealth, the state reduced taxes on timber and chicle exports. To make up for this lost revenue, the state increased taxes on small landowners and peasants. London’s concern that the colony would remain a major drain on resources led to a study of the colony’s finances, conducted by Pim in 1932. He sought to impose strict limits on all state spending except for that related to agriculture and forestry in order to cut “the administrative organizations to the utmost extent,” but without “postponing the prospects of development...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Capitalism qua Development

- Part I: Colonizing the Maya

- Part II: Aporias of Development

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Decolonizing Development by Joel Wainwright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.