![]()

1

Building Codes

The existence of building regulations goes back almost 4,000 years. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi decreed the death penalty for a builder if a house he constructed collapsed and killed the owner. If the collapse killed the owner’s son, then the son of the builder would be put to death; if goods were damaged then the contractor must repay the owner, and so on. This precedent is worth keeping in mind as you contemplate the potential legal ramifications of your actions in designing and constructing a building in accordance with the code. The protection of the health, safety and welfare of the public is the basis for professional licensure and the reason that building regulations exist.

“If a builder build a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

If it kill the son of the owner, the son of that builder shall be put to death.

If it kill a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house.

If it ruin goods, he shall make compensation for all that has been ruined, and inasmuch as he did not construct properly this house which he built and it fell, he shall re-erect the house from his own means.

If a builder build a house for some one, even though he has not yet completed it; if then the walls seem toppling, the builder must make the walls solid from his own means.”

Laws 229-233

Hammurabi’s Code of Laws

(ca. 1780 BC)

From a stone slab discovered in 1901 and preserved in the Louvre, Paris.

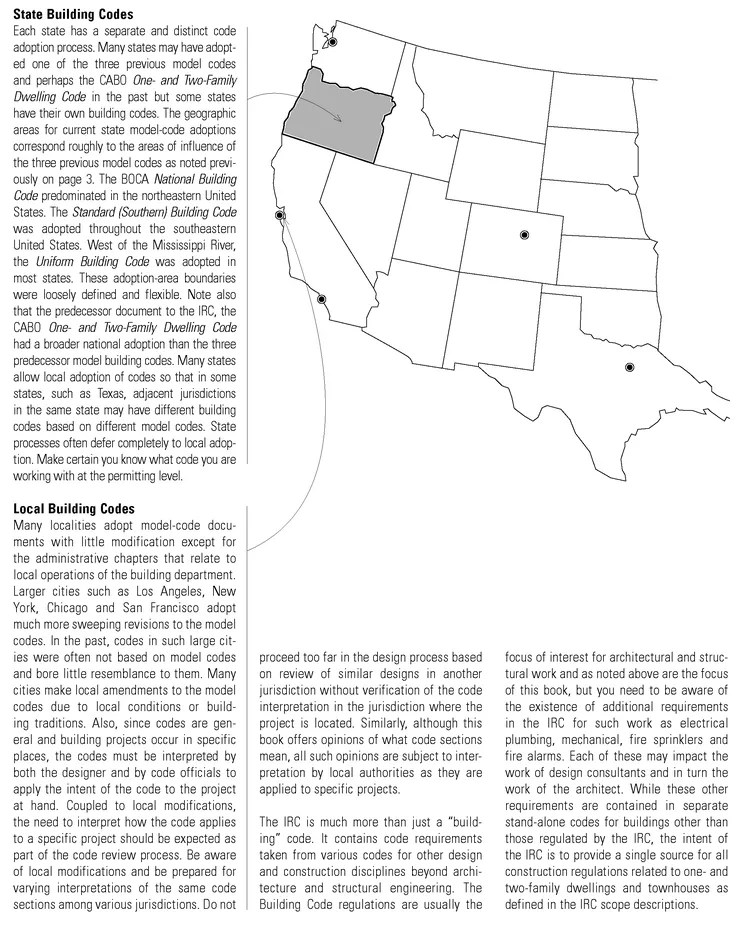

Various civilizations over the centuries have developed building codes. The origins of the codes we use today lie in the great fires that swept cities regularly in the 1800s. Concerns about fire regulations in urban areas can even be seen dating as far back as the Great Fire of London in 1666. Chicago developed a building code in 1875 to placate the National Board of Fire Underwriters who threatened to cut off insurance for businesses after the fire of 1871. It is essential to keep the fire-based origins of the codes in mind when trying to understand the reasoning behind many code requirements.

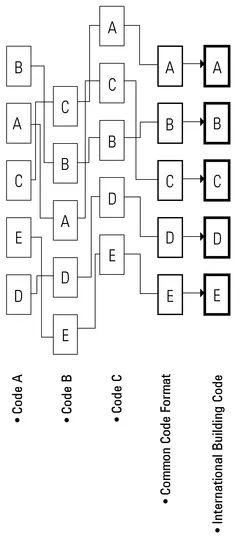

The various and often conflicting city codes were refined over the years and began to be brought together by regional nongovernmental organizations to develop so-called “model codes.” These model codes were developed and written by members of the code organizations. The codes were then published by those code organizations. Model codes are developed by private code groups for subsequent adoption by local and state government agencies as legally enforceable regulations. The first major model-code group was the Building Officials and Code Administrators (BOCA), founded in 1915. They published the BOCA National Building Code. Next was the International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO), formed in 1922. The first edition of their Uniform Building Code was published in 1927. The Southern Building Code Congress, founded in 1940, published the Standard (Southern) Building Code.

These three model-code groups published the three different building codes previously in widespread use in the United States. These codes were developed by regional organizations of building officials, building materials experts, design professionals and life safety experts to provide communities and governments with standard construction criteria for uniform application and enforcement. The ICBO Uniform Building Code was used primarily west of the Mississippi River and was the most widely applied of the model codes. The BOCA National Building Code was used primarily in the north-central and northeastern states. The SBCCI Standard Building Code was used primarily in the Southeast. The model-code groups have merged together to form the International Code Council and have ceased maintaining and publishing their own codes. Also included in this merger was the incorporation of the Council of American Building Officials (CABO) into the International Code Council. CABO published the One- and Two- Family Dwelling Code. This code, which was limited in coverage to the types of occupancies noted in its title, was the closest thing to a national model building code in the decades preceding the development of the International Building Code.

The International Building Code

Over the past few years a real revolution has taken place in the development of model codes. There was recognition in the early 1990s that the nation would be best served by comprehensive, coordinated national model building codes developed through a general consensus of code writers. There was also recognition that it would take time to reconcile the differences between the existing codes. To begin the reconciliation process, the three model codes were reformatted into a common format. The International Code Council, made up of representatives from the three model-code groups, was formed in 1994 to develop a single model code using the information contained in the three current model codes. While detailed requirements still varied from code to code, the organization of each code became essentially the same after the mid-1990s. This allowed direct comparison of requirements in each code for similar design situations. Numerous drafts of the new International Building Code were reviewed by the model-code agencies along with code users. From that multiyear review grew the International Building Code (IBC), first published in 2000. There is now a single national model building code, maintained by a group composed of representatives of the three prior model-code agencies, the International Code Council, headquartered in Washington, D.C. This group was formed from a merger of the three model-code groups and CABO into a single agency to update and maintain the “I Code” family, which includes the International Building Code and the International Residential Code.

The International Residential Code

In addition to the International Building Code (IBC) there is the International Residential Code (IRC). This stand-alone code is meant to regulate construction of detached one- and two-family dwellings and townhouses that are not more than three stories in height with a separate means of egress. This code is designed to supplant residential requirements contained in the IBC in jurisdictions where the IRC is adopted.

The IRC is derived from a predecessor residential building code published by the Council of American Building Officials (CABO), the One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code. In 1996 CABO and the predecessor code organizations that ultimately became the International Code Council agreed to begin development of an updated stand-alone national model residential building code. This resulted in the first publication of the International Residential Code in 2000. This code includes provisions that replace the requirements of the International Building Code with requirements specific to buildings within the scope of the IRC. The IRC includes provisions for code requirements for all the systems typically contained in the one- and two-family buildings and townhouses regulated by the IRC. Among these “external” codes are the electrical sections of the IRC, which are taken from NFPA 70: National Electrical Code. The electrical chapters are produced under the auspices of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), which produces and copyrights the National Electrical Code. The IRC also contains materials regarding fuel gas provisions included through an agreement with the American Gas Association (AGA). [Note this book focuses on the first 10 chapters of the IRC, the requirements related to building design and construction, and does not address IRC requirements for such things as electrical or plumbing work.]

Note also that many local jurisdictions make other modifications to the codes in use in their communities. For example, many jurisdictions make amendments to require fire sprinkler systems, even in single-family residences, where they may be optional, or not even required, in the model codes. In such cases mandatory sprinkler requirements may change the design options offered in the model code for inclusion of sprinklers where not otherwise required by the code. It is imperative that the designer determines what local adoptions and amendments have been made in order to be certain which codes apply to a specific project.

There are also specific federal requirements that may need to be considered in design and construction in addition to the locally adopted version of the model codes. Among these are the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1988. While knowledge of these regulations will promote universal design for access to housing for persons with disabilities, note that these regulations typically do not apply to the types of buildings regulated by the International Residential Code. Accordingly they will not be discussed in any detail in this book.

Code Interactions

The Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJ)—a catch-all phrase for all planning, zoning, fire and building officials having something to say about buildings—may not inform the designer of overlapping jurisdictions or duplicate regulations. Fire departments often do not check plan drawings at the time building permit documents are reviewed by the building department. Fire and life-safety deficiencies are often discovered at the time of field inspections by fire officials, usually at a time when additional cost and time is required to fix these deficiencies. The costs of tearing out noncomplying work and replacing it may be considered a designer’s error. Whenever starting a project, it is therefore incumbent upon the designer to determine exactly which codes and standards are to be enforced for the project and by which agency. It is also imperative to obtain copies of any revisions or modifications made to model codes by local or state agencies. This must be assured for all AHJs.

The model codes have no force of law unto themselves. Only after adoption by a governmental agency are they enforceable under the police powers of the state. Enforcement powers are delegated by state or local statutes to officials in various levels of government. Designers must verify local amendments to model codes to be certain which code provisions apply to specific projects.

There are many different codes that may apply to various aspects of construction projects. Typically the first question to be asked is whether the project requires a permit. There are typically cost thresholds for when permits are required. These are usually set by local amendments to model code provisions. Certain projects, such as interior work for movable furniture or finishes, are usually exempt. Carpeting may be replaced and walls painted without a permit, but moving walls, relocating doors, or doing plumbing and electrical work will require a permit in most jurisdictions.

Traditionally, codes have been written with new construction in mind. In recent years more and more provisions have been made applicable to alteration, repair and renovation of existing facilities. For renovation work it is critical to define the scope of alteration or addition work to be able to define the area where the code applies to the work. The code does not come into effect in those areas not impacted by the work. The code requires new work to meet the current code, but does not require remedial work in those areas not affected by the new work. It is typically not required to bring a whole house up to the new code in those areas not impacted by new work. Again, this should be verified against local code requirements.

Standard of Care

The designer should always remember that codes are legally and ethically considered to be the minimum criteria that must be met by the design and cons...