![]()

PART I

THE CONTEXT

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Roots

Personal and Professional

Although my personal roots and those of my chosen discipline are not identical or even parallel, I believe it is useful for the reader to know something of the background of the practitioner as well as of the origins of the profession. Both provide the context within which this book was written and can best be understood. I begin, therefore, with some thoughts about the sources of my own childhood interest in art, in order not only to introduce myself, but also to offer some ideas about how and why art is therapeutic.

Personal

The roots of my interest in art are deep and old and personal. And even after many years of psychotherapy, I am still not sure of all of the meanings for me of making, facilitating, and looking at art. I know that sometimes my pleasure was primarily visual. Like all children, I was curious about what could not be seen, what was hidden inside the body or behind closed doors. So it was exciting to be able to look with wide-open eyes, because in art looking was permissible, while it was so often forbidden elsewhere. I still find it fascinating to look at art, which is, after all, private feeling made into public form.

Just as my often-insatiable hunger felt somehow appeased when receiving art supplies, especially brand-new ones, so looking at art had a nourishing quality as well. It was a kind of taking-in, a drinking-in with the eyes of a delicious visual dish. Viewing a whole exhibit of work I liked was at least as fulfilling for me as eating an excellent meal.

If looking at art was a kind of validated voyeurism, the making of products was a kind of acceptable exhibitionism. So too the forbidden touching, the delight in sensory pleasures of body and earth, put aside as part of the price and privilege of growing up—these were preserved through art in the joy of kneading clay or smearing pastel.

Not only was art a path to permissible regression; it was a way to acceptable aggression as well. The cutting up of paper or the carving of wood, the representation of hostile wishes—these were possible through art, available to me, as to others, in the many symbolic meanings inherent in the creative process.

Many years ago, I found a drawing made when I was 5. It contained some aesthetically interesting designs and was developmentally appropriate. It allowed me to articulate what I knew about the human body and to practice my decorative skills. More important symbolically, it represented the fantasied fulfillment of two impossible wishes: to be my king-father’s companion as princess-daughter (or even queen) and to be like him—to have what he had (the phallic cigarette) that I lacked (the legs are missing on the girl). The drawing was also done for him, a gift that probably brought praise for its very making and giving.

Sometimes art became for me, as for others, a way of coping with trauma too hard to assimilate (DVD 1.1). When I was 17, my friend Peter suddenly died. He had been young, handsome, and healthy; president of our class, ready to go on to a bright career in college and the world. In a crazy, senseless accident at high altitude, he stepped off the edge of a Colorado mountain and crashed to his end. Numbly, I went home to the funeral from the camp where I was working as an arts and crafts counselor. Numb, I returned to camp, then succumbed to a high fever for several anguished days and nights.

When I awoke, there was a strong need to go to the woods and paint. On my first day off I did, and it was good. The painting was not of Peter, but of a person playing the piano, making music in dark reds, purples, and blacks (1.1A). It was a cry, a scream caught and tamed. It was a new object in the world, a symbolic replacement for he who was lost, a mute, tangible testament. The doing of it afforded tremendous relief. It did not take away the hurt and the ache, but it did help in releasing some of the rage, and in giving form to a multiplicity of feelings and wishes.

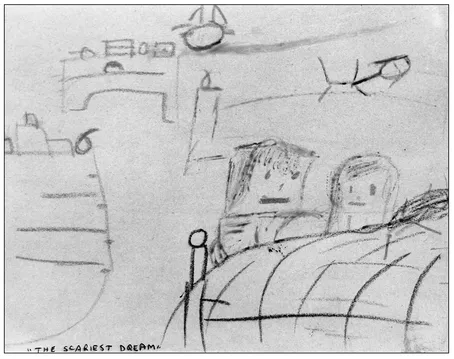

So too with a remembered nightmare, finally drawn and then painted, given form and made less fearful (1.1B). Years later I was to discover, much to my surprise, that drawing a recurrent scary dream (Figure 1.1) would help my daughter to finally sleep in peace. Only now do I begin to understand the mechanism, the dynamics, the reason behind this miracle of taming fear through forms of feeling. I think it is what the medicine men have known for so long: that giving form to the feared object brings it under your own symbolic control.

1.1 “The Scariest Dream” (Two Dead Grandmothers). Age 8. Chalk

Waking as well as sleeping fantasies evoked images that invited capture on canvas. A powerful, insightful revelation of ambivalent feelings toward my formerly idealized mother during my analysis stimulated a rapidly done expressionistic painting, which still evokes tension (1.1C). As an externalization of how and what I was feeling, however, it gave both relief and a greater sense of understanding. The push and pull of conflict was translated into paint, reducing inner anguish through outer representation.

Not only the making but also the perceiving of art was of vital importance to me as I grew up. As a young child I stared long and hard at a Van Gogh reproduction that hung on our living room wall. The Sunflowers were so big and alive, so vivid and powerful, that even in a print they seemed to leap forth from the canvas. And later, as a teenager, I recall the drunken orgy of a whole exhibit, with room after room full of original Van Goghs, wild and glowing. Each picture was more exciting than the last—the intensity and beauty of the images, the luscious texture of the paint—like the “barbaric yawp” of author Thomas Wolfe, another of my adolescent passions.

Many a weekend afternoon was spent sitting transfixed before some of my favorite paintings in the Museum of Modern Art. I think I must have studied every line in Picasso’s Guernica, yet I am still moved by its power. A large Futurist painting called The City was an endlessly fascinating, continually merging sea of images. And another large painting by Tchelitchew, Hide and Seek, never ceased to magnetize my mind, to both repel and attract, with its heads and guts and fleeing figures. Surely there is much in art that feels therapeutic to the viewer, as well as to the artist.

As I write many images return, all vivid and bright and full of the feelings they stimulated and echoed. No wonder I embraced the art history major required for studio art courses at Wellesley. For there I experienced what André Malraux (1978) called the “Museum Without Walls”—the projection of an image magically magnified, glowing forth in the darkened room, giving one the illusion of being alone with a “presence”—despite the many other students, equally transfixed by its power and the music of the lecturer’s voice. As an artist said once in a television interview, “Art is the mediating object between two souls. You can actually feel there’s somebody there who’s trying desperately to communicate with you.”

Professional

This “magic power of the image” (Kris, 1952) is also one of the ancient roots of the discipline of art therapy. The use of art for healing and mastery is at least as old as the drawings on the walls of caves; yet the profession itself is a youngster in the family of mental health disciplines. In a similar paradox, while art therapy itself is highly sophisticated, the art process on which it rests is simple and natural.

On a walk through the woods some years ago, I came across a self-initiated use of art to cope with an overwhelming event, reminding me of my own painting after the tragedy of Peter’s death. A rural man—a laborer—had carved a powerful totemlike sculpture out of a tree trunk, as part of mourning the untimely death of his young wife (DVD 1.2). His explanation to me was that he “just had to do something,” and that the activity of creating the larger-than-life carving had seemed to fit his need, perhaps helping to fill the void left by his loss.

Similarly, people caught in the turmoil of serious mental illness and threatened by loss of contact with reality have sometimes found themselves compelled to create art (DVD 1.3) as one way of coping with their confusion (1.3A). Such productions (1.3B), even found on scraps of toilet paper or walls (1.3C), intrigued psychiatrists and art historians in the early part of the twentieth century (Prinzhorn, 1922/1972). Fascinated by these outpourings of the troubled mind (1.3D), they collected and studied such spontaneous expressions, hoping to better understand the creators and their ailments (1.3E).

With the advent of depth psychology (Freud, 1908, 1910; Jung, 1964), therapists looked for ways to unlock the puzzle of primary process (unconscious, illogical) thought, and tried to decode the meanings of images in dreams, reverie, and the art of the insane (Jakab, 1956/1998; MacGregor, 1989). The growth of projective testing in the young field of clinical psychology stimulated further systematic work with visual stimuli such as the Rorschach inkblots or drawings, like those of the human figure, primarily for diagnostic purposes.

While these developments were occurring in the area of mental health, educators were discovering the value of a freer kind of artistic expression in the schools. Those in the progressive movement (Naumburg, 1928) were convinced that the creative experience was a vital part of any child’s education, essential for healthy development (Cane, 1951). Some art educators were especially sensitive to the value of personal expression in helping children deal with frustration and self-definition (DVD 1.4). One, Viktor Lowenfeld (1952, 1957, 1982), developed what he called an “art education therapy” for children with disabilities (1.4A). During that time, art was beginning to be offered as therapy to patients in general hospitals (Hill, 1945, 1951) and in psychiatric settings.

The two women most responsible for defining and founding the field of art therapy began their work with children—in a hospital (Naumburg, 1947) and in a special school (Kramer, 1958)—on the basis of their experiences as educators. Both were Freudian in their orientation, though each used different aspects of psychoanalytic theory to develop her ideas about the best therapeutic use of art.

For Margaret Naumburg (1950, 1953, 1966) art was a form of symbolic speech coming from the unconscious, like dreams, to be evoked in a spontaneous way and to be understood through free association, always respecting the artist’s own interpretations (1.4B). Art was thus conceived as a “royal road” to unconscious symbolic contents, a means of both diagnosis and therapy, requiring verbalization and insight as well as art expression.

For Edith Kramer (1971, 1979, 2000, 2001) on the other hand, art was a “royal road” to sublimation, a way of integrating conflicting feelings and impulses in an aesthetically satisfying form, helping the ego to control, manage, and synthesize via the creative process itself (1.4C). Both approaches are still visible in a field that has grown extremely rapidly over the last 50 years. This rapid development reflects the power of art as a therapeutic modality. I never cease to be amazed at the potency of art therapy, even in the hands of relatively naive practicum students.

Since it is so powerful, it is fortunate that no longer can “anyone with a paint brush and a patient” declare him- or herself to be an art therapist (Howard, 1964, p. 153). Indeed, my own learning experiences—in the era before formal education was available in the field—bear witness to the need for clinical training for anyone whose background is solely in art and education.

Personal/Professional Passage

The roots of my interest in art, as noted earlier, lay deep in the soil of my childhood and adolescence, before blossoming into a variety of roles—teacher of art to neighborhood children in high school, arts and crafts counselor at summer camps, art major in college, and later, art educator (of children, then of teachers), art researcher, “art lady” (Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on PBS), art consultant, and—eventually—art therapist.

When I first discovered the field, I felt like the ugly duckling who found the swans and no longer saw himself as a misfit. As an artist, I never felt talented enough to make a career of my painting. And, as a teacher, although I loved working with children, I was often uncomfortable with the methods of my fellow teachers—like asking children to fill in stenciled drawings, or using a paddle for discipline.

In 1963, when the Child Development Department at the University of Pittsburgh invited me to offer art to schizophrenic children, I was in no way a clinician. But the work was such a pleasure and a challenge, and the support from others was so available, that I was able to find places to grow and people to help me.

I first sought the guidance of the two pioneers in art therapy mentioned earlier, each of whom gave generously of her time and thought. Both suggested that I learn about myself through personal therapy and that I learn about being a therapist through supervised work under an experienced clinician.

I was fortunate to find both a mentor and a setting where I was able to learn the necessary skills and practice my trade. As I began to feel like a real therapist,...