![]()

CHAPTER 1

THEORY IN HEALTH PROMOTION PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

Richard A. Crosby

Michelle C. Kegler

Ralph J. DiClemente

PROMOTING HEALTHY BEHAVIOR

One commonly used definition of public health is “the science and art of protecting and improving community health through health education, promotion, research, and disease prevention strategies” (Association of Schools of Public Health, 2006). Notably important in this definition is that “public health” is not synonymous with “health care.” Indeed, the lion’s share of any health care system’s resources is dedicated to providing clinical and diagnostic services. For example, in the United States, our health care budget exceeds $1 trillion annually; however, only about 1 percent is allocated to population-based prevention. A landmark report in the 1970s noted that health is based largely on human biology, environment, and lifestyle, with health care playing a much smaller role in preventing mortality (Lalonde, 1974). Although adequate health care services remain critical, equally critical are efforts to “move upstream” and prevent the causes of morbidity. Thus, public health adopts a proactive approach that is based solidly on the premise that health is a product of lifestyle, shaped heavily by social and physical environments. As such, diverse strategies can be employed to substantially alter risk behaviors and environments and, in so doing, markedly change the disease trajectory and reduce morbidity. The mission of public health is to fulfill “society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1998, page 7). This mission is based on the premise that multiple aspects of the environment (physical, economic, legal, political, cultural, and so on) act as powerful determinants of health as well as health-related behaviors. The differences between treating disease, as exemplified in the health care approach, versus modifying lifestyle and environments, as exemplified in a public health approach, have been eloquently described in a recent text entitled, Prescription for a Healthy Nation (Farley and Cohen, 2005).

The practice of public health, then, can be viewed as a diverse array of strategies, methods, and efforts that are designed to protect people by mitigating risk factors associated with morbidity and premature mortality and by creating environments that are conducive to healthy practices. Given that the basic purpose of public health practice is to prevent morbidity and premature mortality, it is important to have an understanding of the causes of disease, disability, and death. In a classic article, McGinnis and Foege (1993) articulated actual causes of death in the United States. A recent update of this work provides a foundation for understanding how changing health behavior can lead to improvements in the health of the public (Mokdad et al. 2004). The top ten “offenders” are shown below in descending order of importance.

• Tobacco use

• Poor diet and physical inactivity

• Alcohol use

• Infection with microbes

• Toxins

• Motor vehicle crashes

• Firearm trauma

• Sexual risk behaviors

• Illicit drug use

Consider just the first two actual causes of death. Collectively, tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity account for about 35 percent of all premature deaths in the United States. The implications for public health are simple and obvious, yet the solutions are elusive and complex. It is obvious that the health of the public would be greatly improved if people would stop smoking and overeating and begin exercising on a routine basis. But identifying solutions to these health problems is “elusive and complex.” Smoking, overeating, and sedentary lifestyles are culturally ingrained for many Americans. Moreover, private sector forces with vested fiscal interests have supported, reinforced, and promoted behaviors that are clearly deleterious to the health of Americans. The obvious question then is: Where does one even begin the seemingly insurmountable task of reversing this trend?

Even relatively “small” changes in health behavior may yield substantial benefits to public health.

Looking at the remainder of the items representing actual causes of death, it becomes apparent that changing health behavior is the likely turning point for protecting the public from harm. Even relatively “small” changes in health behavior may yield substantial benefits to public health.

For example, the simple elimination of table salt could result in a 20 percent nationwide decrease of stroke (Law et al., 1991). Of course, removing salt-shakers from all eating tables in the United States is a formidable challenge. Meeting this challenge involves providing health education about the health hazard of adding salt to foods and is contingent upon people’s willingness to comply with this health-protective information, a type of “medical advice,” when they feel perfectly healthy and, as important, have cultivated a taste for salt in their food. The question then becomes, are health promotion efforts always at the mercy of public acceptance? To answer this question, a second example is needed.

Tobacco use illustrates how even a seemingly small change in health behavior can yield substantive rewards in public health. In 1989, the state of California imposed a tax on the sale of cigarettes (25 cents per pack). Estimates suggest that this tax led to at least a 5 percent decline in tobacco use (Flewelling et al., 1992), to which, in the ensuing decade, the 20 percent decline in heart disease-related mortality was partly attributable (Fichtenberg et al., 2003). In this example, the change in health behavior was related to a carefully calibrated change in policy (increasing cigarette tax) as a means of discouraging use. The additional financial pressure exerted through the tax acted as a catalyst by providing a tangible, and important, incentive to reduce smoking.

Although vastly different from each other, the aforementioned examples regarding table salt elimination (a lifestyle change) and taxation of cigarettes (a change to the environment) illustrate that changes in health behavior can markedly effect reductions in morbidity and mortality. In fact, a nearly infinite number of health-protective behaviors could be listed. Many of these may be simple, one-time acts, such as testing your home for radon or being vaccinated for diseases like tetanus or measles. Others may require periodic repetition, such as semi-annual dental cleanings, Pap testing, or screening for high cholesterol. However, the majority of health-protective behaviors require constant (often daily) repetition. Examples include: eating high-fiber, low-fat foods; drinking clean water; engaging in aerobic exercise, and maintaining musculoskeletal health through stretching and weight-bearing exercises. Many of the behaviors requiring constant repetition are avoidance behaviors, such as avoiding toxins in the environment (including environmental tobacco smoke); abstaining from the use of illicit drugs and the use of more than moderate amounts of alcohol; not using tobacco; not consuming foods associated with an increased risk of heart disease, cancer, or diabetes; and not engaging in unprotected sex that could lead to infection with sexually transmitted pathogens, including HIV. Still other repetitive behaviors entail daily habits such as safe driving practices and the intentional practice of home and workplace safety.

The profound role of social determinants in shaping health behavior is becoming increasingly apparent. The influence of social capital, for example, is well-documented. Culturally ingrained health-risk behaviors are common in every nation of the world and serve to remind us that social norms are powerful antecedents of health behavior. Entire epidemics can rightfully be said to proliferate as a consequence of unyielding adherence to socially accepted practices, as happened with the AIDS epidemic in that millions of people resisted advice to use condoms to prevent acquisition and transmission of HIV. With respect to chronic disease, two extremely critical health behaviors, diet and physical activity, are largely products of social customs, traditions, and norms. Given the strength of social determinants in shaping health behavior, the expanding role of macro-level theory in fostering the long-term adoption of health-protective behaviors is clearly a valuable asset to public health practice.

Regardless of the exact approach used, public health is achieved through carefully designed efforts to foster health-protective behavior, not through surgery or medicine. In the words of former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, “Health care is vital to all of us some of the time, but public health is vital to all of us all of the time.” Thus, the mandate of public health is deeply rooted in the process of influencing people to adopt healthy behaviors. Herein lies the ultimate challenge to public health: “how can such change be achieved?” The answers to this fundamental question are nearly as infinite as the number of health behaviors; however, they all share one common thread—theory! Although theory is not a panacea, it has been embraced by the public health profession as a means of guiding investigation (research) and informing the content of health education and health promotion efforts.

THE ROLE OF THEORY IN HEALTH BEHAVIOR

Understanding the application of theory to changing health behavior requires mastery of a few fundamental concepts. This section of the chapter will begin by briefly addressing these.

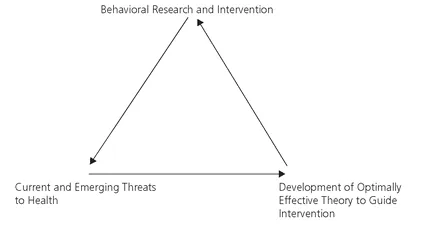

Fundamental Concept 1: Theory Is Dynamic

Theories are seldom static; instead they change and evolve to better serve public health (Crosby, Kegler, and DiClemente, 2002). The evolution of theory refers generically to the discipline of health promotion rather than focusing on the improvements made within existing theories. For example, the concept of natural helper models is a relatively new method of effectively leveraging change in health behaviors. Rather than being an improvement over a previous version of a single theory, natural helper models represent a true innovation in the paradigm used to change behavior. Indeed, innovative paradigms are the seed of this evolutionary process. The evolutionary process is vital because the challenges in public health change, as do the populations served. As practice needs change, research is conducted to help identify new solutions in the form of health promotion strategies, methods, techniques, and policy. Theories are utilized to inform these solutions. Solutions are tested using rigorous evaluation methodologies designed to isolate and quantify the effect of the solution on health behavior. By identifying efficacious “solutions” and assessing the link between the underlying theory and behavior change, we strengthen the empirical evidence in support of theory. Theory, however, must also be able to accommodate new and emergent challenges to public health. Thus, theory must be capable of adapting to the needs imposed by established or emergent threats to public health.

Theory must be capable of adapting to the needs imposed by established or emergent threats to public health.

Theory cannot be rigid, simply because people and public health issues are diverse and continually evolve. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Fundamental Concept 2: Theories Have Different Paradigms

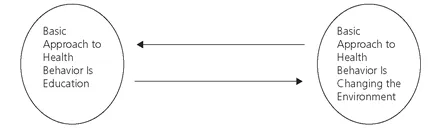

A paradigm may or may not be something that is a recognized part of thinking and problem solving. Frequently, however, scholars may fail to recognize that their thinking is restricted by a given paradigm. In fact, paradigms can sometimes act as blinders, precluding alternative views. Consider, for example, the relatively common problem of hospital-acquired infections. One way to reduce the incidence of these infections is to ensure that all clinical staff thoroughly wash their hands between seeing patients. In an “education paradigm” the solution to this problem would be constantly reminding clinical staff about the problem of hospital-acquired infections and the benefits of thorough hand-washing. Unfortunately, this education-based paradigm often fails to solve the problem, and it offers no other solution beyond intensifying education efforts. Now, consider an ecological approach as an alternative paradigm. Ecological approaches to health behavior change go beyond education by actions such as influencing social norms, building community infrastructures, providing skills and resources that people need to practice healthy behaviors, and by making changes to the physical, economic, legal, political, and cultural environment. Actions that may result from this paradigm might then lead to the discovery that clinical staff members are frequently “pressed for time,” to the point that traversing a long hospital hallway to wash their hands is inconvenient. One potential solution would be installing large hand-washing stations along the hallway to reduce the distance staff have to travel, thus enhancing convenience and, as a direct outcome, hand-washing behavior.

FIGURE 1.1 Relationship Between Theory, Research, and Practice in Public Health

The two examples reflect different perspectives on how best to catalyze behavior change and represent opposing ends on a continuum of theory, as illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Health promotion is exciting because it is dynamic. For example, rather than implementing a staff educational campaign alone or modifying the hospital environment alone, a more effective approach may involve both a change in hospital environment and concomitant staff education regarding the benefits of hand-washing. Together, modification of the hospital environment and staff education may be more effective at promoting the desired behavior change than either strategy alone. Creatively designing “solutions” to enhance health implies the necessity of understanding the barriers to adopting health-protective behaviors. It also means developing new strategies to inform and motivate individuals and manipulate social/environmental contingencies to catalyze the long-term adoption of health-protective behaviors.

FIGURE 1.2 A Continuum of Theory

Fundamental Concept 3: Theories Have Multiple Functions

Students of behavioral theory have often raised inquiries such as “Why couldn’t there be just one theory that does it all?” or “Would it be possible to know just one or two theories really well and still serve the goals of public health?” Unfortunately, the answer to both questions would be “no,” simply because theory aids public health intervention efforts in multiple ways, depending on the specified objectives to be achieved.

A convenient way to think about any intervention effort is to view the process as occurring in three sequential phases. The first phase would be to ask and empirically answer two fundamentally discrete, though related, questions: (1) Why do people engage in behaviors that increase their risk for adverse health outcomes; and (2) What factors predict adoption of health-protective behaviors? For convenience, we can refer to the first phase as the “why” phase. In this phase of the overall effort to develop an effective health promotion program, the program objectives will be developed based on theory-guided investigation.

The next phase involves understanding how people go about the somewhat cumbersome process of actually adopting, performing, and possibly repeating the health-protective ...